By John Anthony S. Estolloso

HATE THE statement or agree with it, the Filipino brand of humor is essentially slapstick. We relate more to the monkeyshines of The Three Stooges, with all the beatings, verbal abuse, smart-shaming, and corollary brain damage, than the sarcastic wit and wordplay of the Marx Brothers; simply put, we laugh to escape the tedious demand of thinking. Needless of its needles, slapstick sticks around.

That may be the reason why theatrical comedy does not hold much sway among local audiences. Whether because of the shows’ unavailability or basically just our homegrown aversion to looking for humor between the lines of live acting, most of us would rather prefer to gawk and giggle at televised noontime shows.

My first encounter with an excellently staged dramatic comedy would be Leoncio P. Deriada’s ‘Distrito de Molo’. Directed by Tony Mabesa in the old theater of UP Visayas some years ago, the play promenaded the audience with vignettes of local scenes and sins – sarcastically witty yet homely familiar enough to induce theatergoers to raucous peals of laughter.

‘Distrito de Molo’ was a comedic mirror to the laidback Ilonggo way of life. There was the spite-laced banter of three spinster sisters on why they were named after notable elementary schools in Iloilo City, and that one of them was named after an all-girls institution (then) situated by General Luna Street: the audience had no qualms in glancing at the red tartans of the plaid-clad ladies with much mirth. When a naked statue of Atlas came to life in the next segment and berated his owner’s prudery, on how ‘the people at Loyola Heights’ failed to teach him about appreciating culture and the arts, the audience sleazily side-eyed the blue-and-white uniformed students of the local Jesuit school with suppressed smirks. (We crouched on our seats, of course.)

That evening was a revelation. In all appearances, the Ilonggos can indulge in dramatic humor between the lines after all, and sans lame puns, bludgeonings, or insults, we can laugh at the foibles and follies of ourselves without feeling a glint of insult or indignation. The theater held up a mirror to our laughable whimsies and we humorously took it with a grain of salt: ‘Distrito de Molo’ was outrageously funny because it was truthful.

Much as this author would believe that the production of Deriada’s play was an isolated triumph of dramatic comedy, he is proved wrong by a company of intrepid young people who recently took to the stage to produce a sophisticated farce of the theatrical experience. Though this brave dramatic enterprise was staged some years after ‘Distrito de Molo’, the reception might just say something about the local theatrical taste. Have we transcended our penchant and patronage for infantile Disneyfied stage adaptations as standards for comedy onstage? Have we matured theatrically as an audience?

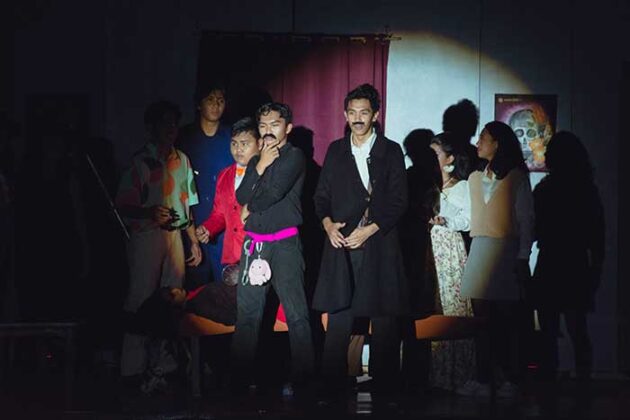

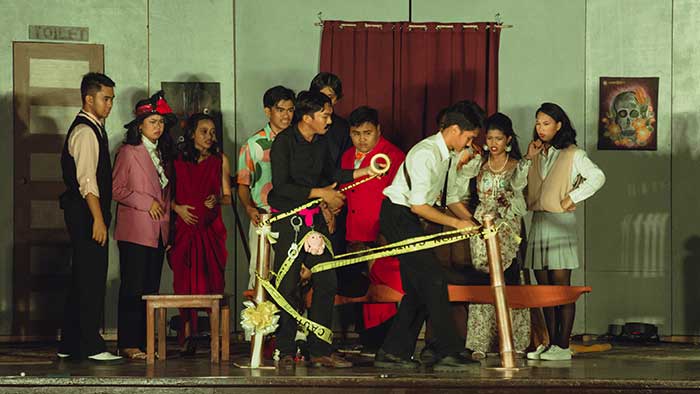

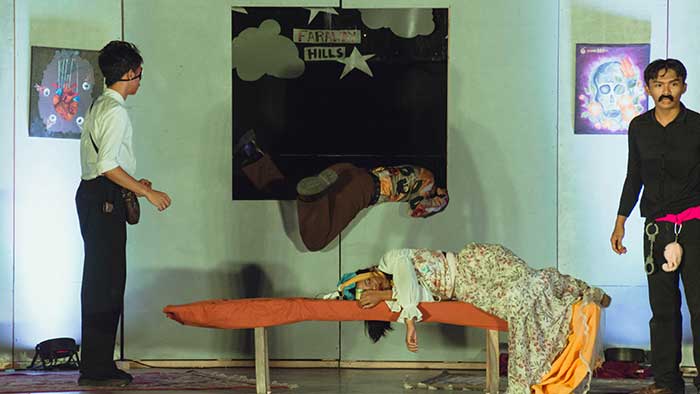

Less than a fortnight ago, a batch of senior high students of Gamot Cogon Waldorf School staged a theatrical rendition of a whodunit, cut to the dimensions of a play where everything goes wrong. There were the “missplleed” title on the tickets, misplaced and mismatched props, the forgotten lines on cue, the sets and props that seemed set on killing everyone on stage, the ‘accidents’ caused by ‘mistaken’ cues, and the crafty incoherence that eloquently held the narrative together. The whole lot was a mess.

The story was – well, there was no exact story. Rather, it was a rambling farce of not what to do onstage. One may call it a cautionary tale but as to what it exactly cautions is drowned in the comedy: it was just simply a series of murder and mayhem most British. Everything collapsed by the end of the play: the lights, the props, the set, the dialogue, the coherence, the director’s composure – a most excellently choreographed disaster of comic proportions that rightly deserved the resounding applause at the end of it all. Altogether, it was an antiplay worthy of (non)emulation, reaching out beyond the amateur and the crude.

For all the shenanigans running amok onstage and the pell-mell spontaneity sparking sporadically in the scenes, the play presented its audience with something to ponder about: if senior high students can accomplish this level of sophisticated comedy to rave reviews, what is stopping our local theater companies and groups from elevating our homegrown state of humor?

If the purpose of performative art is to jar us from the complacent condition of current aesthetics, should this senior high production not be a clarion call enough to sophisticate the comedies we stage?

(The author is the subject area coordinator for Social Studies of above-hinted Jesuit school. Photos are from Arsen Carl Mabagos Vargas and Andrew Pasaporte.]