By Klaus Döring

Why is Mozart’s music good for the brain?

A study found that subjects who listened to Mozart showed significantly increased spatial reasoning skills for at least 10 to 15 minutes. This finding led crèches in the United States to start playing classical music to children.

During my high school years, I discovered that listening to Mozart was indeed helpful.

The Mozart effect is the theory that listening to Mozart’s music can induce a short-term improvement in the performance of certain cognitive tasks. Researchers found that listening to Mozart’s music enhanced word memory across positive, negative, and neutral words.

One of the most persistent myths in parenting is the so-called Mozart effect, which claims that listening to music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart can increase a child’s intelligence.

Claudia Hammond wrote about it in 2013: “It is said that classical music could make children more intelligent, but when you look at the scientific evidence, the picture is more mixed.”

You have probably heard of the Mozart effect. It’s the idea that if children or even babies listen to music composed by Mozart, they will become more intelligent. A quick internet search reveals plenty of products to assist you in this task. Regardless of your age, there are CDs and books to help harness the power of Mozart’s music, but when it comes to scientific evidence that it can make you more intelligent, the picture is more mixed.

After a short period, I sought more and suddenly “Master” Ludwig van Beethoven stepped into my musical life: “Dadadadaan…”

I strongly agree with François Mai, who wrote: “Beethoven was the first of the Romantic period composers who dominated classical music during the 19th century. He himself was a passionate man who wore his feelings on his sleeve. He had episodes of depression accompanied by suicidal ideas and rarer episodes of elation with flights of ideas. The latter are reflected in some of his letters. He had a low frustration tolerance and at times would become so angry that he would come to blows with others such as his brother Carl, or he would throw objects at his servants. Although he never married, he had several affairs, including one with a married woman who has come to be known to posterity as ‘the Unknown Beloved.’ To her, he wrote three love letters filled with affection and feeling. He much enjoyed wine, which resulted in hepatic cirrhosis that caused his premature death at the age of 56.”

This moodiness is reflected in his music. The “Marches Funébres” of his Third Symphony (Eroica) and the Piano Sonata, op. 26, no. 12, are poignant and powerful portrayals of grief and bereavement. The final movement of the String Quartet, no. 6, op. 18 (La Malinconia), has sudden and alternating changes of tempo and rhythm that depict, in musical terms, the mood changes that occur in bipolar disorder. The pace and fortissimo dynamics of both his Rondo a Capriccio for piano, op. 129, and the storm movement of his Sixth Symphony (Pastoral Symphony) beautifully (or perhaps one should also say fearfully) display anger and agitation.

Beethoven’s and my moodiness remain the same to this day.

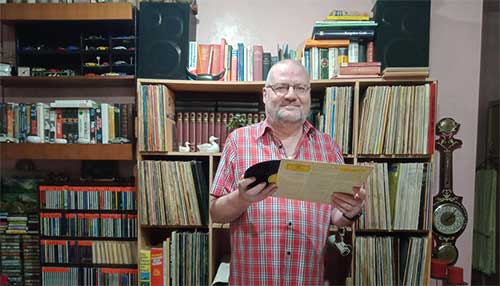

Over the last 50 years, I have met most of my classical masters. This could be a never-ending story. My passion for music is a part of my life—maybe the main part.