By the Institute of Contemporary Economics

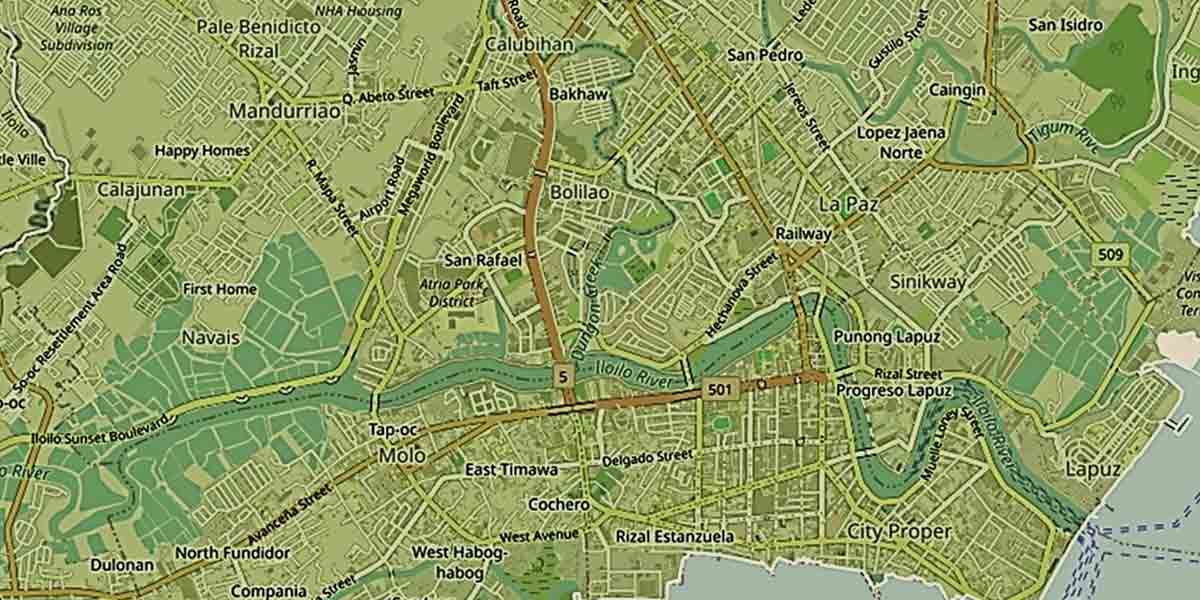

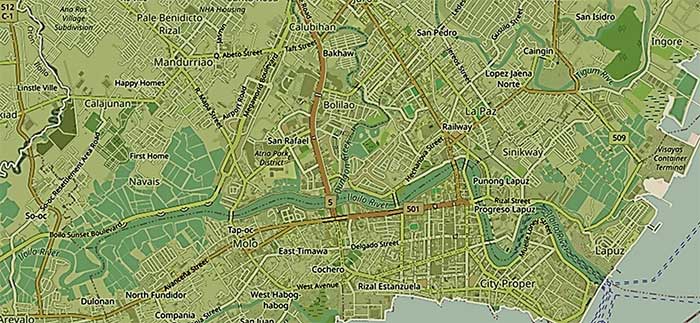

Iloilo City has 180 barangays. With its population of 457,626, that translates to an average population of 2,542. This compares to the national average of 2,602 residents for the 41,911 barangays in the Philippines.

On the surface, Iloilo City is just average. Looking under the hood, however, we see that of these 180 barangays, 55 or 30% have populations of under 1,000 people including 2 which have less than 100 residents. The median population of only 1,810 means that more than half of our barangays do not even qualify to be a barangay, period.

Regardless of size, each barangay will have the same number of Barangay and SK officials. Each of these barangays will ask for, if they already don’t have, a barangay hall, a barangay health center, a multipurpose gym and basketball court, MRF facilities and other such physical infrastructure. The question is – is it worth having these number of barangays?

The question of standing

Section 386 of the Local Government Code (Republic Act 7160) specifies that:

“A Barangay maybe (sic) created out of a contiguous territory which has a population of at least two thousand (2,000) inhabitants as certified by the National Statistics Office except in cities and municipalities within Metro Manila and other metropolitan political subdivisions or in highly urbanized cities where such territory shall have a certified population of at least five thousand (5,000) inhabitants…”

As of the 2020 census, only 23 of Iloilo City’s barangays meet that criteria. Of course, it is possible that by now, some of those barangays may have exceeded the 5,000-population threshold by now. On the other hand, because of out-migration some of those barangays may have also fallen below the threshold set by law. Dividing the population of Iloilo City by the 5,000-population requirement, there should really be only a maximum of 91 barangays in the city, half of what currently exists.

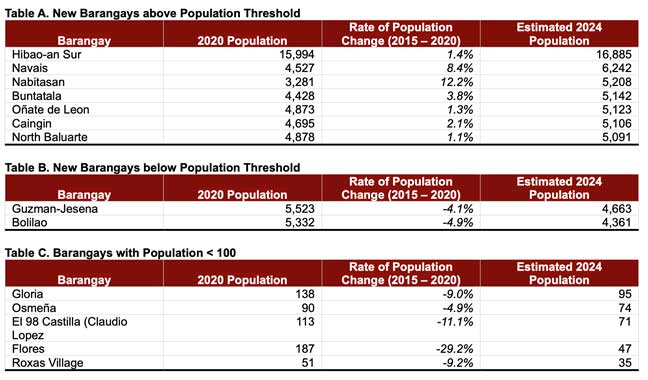

The only way to determine the definitive population of barangays would be to undertake a physical count or to wait for the 2025 census to be conducted by the Philippine Statistics Authority. In the absence of that, we have run calculations to try to get an estimate of the current populations to gauge the number of barangays who may have exceed the population threshold or may have fallen below it. The methodology followed was to use the 2020 census figure and apply the compounded annual rate of population change in the five years immediately preceding this census. These are the results:

The main limitation to the results in the tables above are the use of historical rates of change of population. These may have changed significantly during the years between the last census in 2020 and 2024.

What to do with ‘out of status’ barangays

The Local Government Code does not provide for exceptions for barangays falling below the population threshold except for “indigenous cultural communities”. There is nothing in the law’s Transitory Provisions allowing the “grandfathering” of existing barangays allowing them to continue to exist.

The Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of RA 7160, specifically Article 6, Sections (c), (d) and (f), do provide for the division, merger and/or abolition of barangays and the manner in which these are to be undertaken.

Section (d) states that “(A)n LGU may be abolished when its income, population, or land area has been irreversibly reduced during the immediately preceding three (3) consecutive years to less than the requirements for its creation, as certified by DOF, in the case of income; by NSO, in the case of population; and by LMB, in the case of land area. The law or ordinance abolishing an LGU shall specify the province, city, municipality, or barangay to which an LGU sought to be abolished will be merged with”.

The IRR further states in Section (f) that “No creation, conversion, division, merger, abolition, or substantial alteration of boundaries of LGUs shall take effect unless approved by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite called for the purpose in the LGU or LGUs directly affected”, providing the manner in which these actions are to be decided on.

The loopholes

While it can be surmised that the intent of the law is the consolidation of smaller barangays into larger barangays, it can also be observed that the use of the phrase “may be” in both the law and its implementing rules and regulations provides for an out to this intent. Even if actions are taken to fulfill the law’s intent, the affected residents can ultimately decide not to agree to this via the plebiscite.

The economic argument

The argument for consolidation of barangays jumps off from the economic principle of economies of scale. In simple terms, the larger an entity is the more it can do and the more efficient it is in doing what it can do.

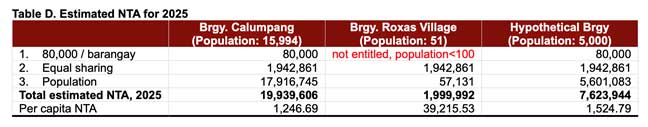

To illustrate, we look at two sample illustrations comparing Barangay Calumpang, the most populous barangay in Iloilo City with 15,994 residents based on the 2020 census and Barangay Roxas Village, the least populous barangay with 51 residents. A third illustration is a hypothetical barangay with a population of 5,000 residents, the cut-off population set by RA 7160. The basis for comparison is the estimated National Tax Allocation (NTA) for these barangays in 2025.

The NTA is the distribution of national taxes wherein the national government receives 60% of these tax collections while local government units (LGUs) receive 40%. Of the 40% allocated for LGUs, barangays receive 20% while 80% is allocated among provinces, cities, municipalities and the National Capital Region.

The allocation for barangays follows this formula:

- P80,000 for each barangay with a population of at least 100

- Equal sharing: 40% of the balance after (1) is divided equally among the 41,911 barangays in the Philippines

- Population: 60% of the balance after (1) is allocated based on the population of a barangay

Based on our understanding of this formula, the indicative amounts to be received by the barangays in our comparison are as follows:

These comparisons would show that Brgy. Calumpang would be the recipient of P19.9 million, Brgy. Roxas Village just under P2 million and our theoretical balangay P7.6 million. There are several observations, inferences and implications that can be drawn from the illustrations in Table D.

- Roxas Village is not eligible for the P80,000 allocation per barangay.

- The amount to be received by Brgy Roxas Village estimated at just under P2 million, does not allow it the flexibility to undertake meaningful development projects for the benefit of its residents.

- The distribution becomes inequitable with the significantly smaller Brgy. Roxas Village receiving 31x more than Brgy. Calumpang and 25x our hypothetical barangay on a per capita basis.

Ironically, because of the relatively small aggregate amount of about P2m it may not actually be able to do much. Under this scenario, it makes better sense for Brgy. Roxas Village to distribute the money to its residents under some form of cash transfer scheme.

In practical terms, the ability of smaller barangays to provide services such as primary healthcare, law and order, waste management and undertake minor basic infrastructure projects (e.g. MRF) is severely compromised by the limited amount of funding that they receive. These barangays will have to rely on their parent LGUs to provide for these projects. On the other hand, larger barangays may actually be able to have surplus funds available. This is quite an inefficient allocation of taxpayer money.

Moreover, over longer periods of time, this inefficiency in fund allocation can lead to uneven and inequitable development. There is of course the incentive for barangays to develop local sources of funding. The NTA, however, is meant to create some level of equity by allocating national resources for our most basic form of government institution. Under current circumstances, with smaller barangays, this cannot happen.

The ultimate good

The legal and economic arguments for larger barangays should not be the only considerations to decide the question of barangay sizes. This has to be balanced by the basic desire of citizens to be as close to decision-making as possible. Smaller political subdivisions would support this desire.

On balance, we believe that the legal and economic considerations outweigh the desire for exceedingly small barangays. Even if citizens are in a better position to communicate with their local leaders, the resolution of the issues that are communicated and the provision of community services is limited by the absence of sufficient financial resources.

While a lot needs to be done to improve the delivery of basic services at the barangay level, an appropriately sized barangay of between 5,000 to 10,000 residents should be able to provide a good balance between the legal, economic and citizen participation considerations.