By Guinevere Latoza and Maujerie Miranda

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

First of two parts

Fathers and mothers passing on their government posts to sons and daughters, as if these were family heirlooms, is nothing new.

But election watchdogs said it was jarring to watch political dynasties flaunt their power during the week-long filing of certificates of candidacy (COCs) this October.

It’s as if October 1 to 8 was a scheduled family reunion for political dynasties who, wearing brand colors, trooped together to Commission on Elections (Comelec) offices across the country to formalize their election bids.

Videos that flooded social media showed a fiesta-like atmosphere as political clans were welcomed by supporters at the venue. In some instances, there were dances, marching bands, and colorful tarpaulins.

A family photo was always taken, streamed live online, followed by interviews where they talked about passing down their elective positions as if they were theirs to give.

“If before the approach was more discreet, not all at once, now it seems like they’re even using the brand… ,” former Comelec Commissioner Luie Tito Guia told the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ).

An uproar followed the COC filing. Rona Ann Caritos, executive director of the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (Lente), said it is an opportunity to recall why political dynasties were prohibited by the framers of the 1987 Constitution.

The prohibition remains unenforced because Congress has yet to pass an implementing law.

“We’ve been through many elections, and this (the rule of political dynasties) has always been the problem. But because some famous personalities, along with their family members, filed under such circumstances, it became a bigger concern,” Caritos said.

Will Congress pass a law against dynasties?

But can Congress be expected to pass a law against political dynasties?

Political science professor Julio Teehankee defines political dynasty as “the concentration, consolidation or perpetuation of political power in persons related to one another.”

“Kapag may kamag-anak ka. And, based on proposed laws, those who are related by consanguinity or affinity — consanguinity by blood of affinity in law. Some say it should extend up to the third degree, while others want it limited to the second degree,” said Teehankee, who has authored several studies on political dynasties in the country.

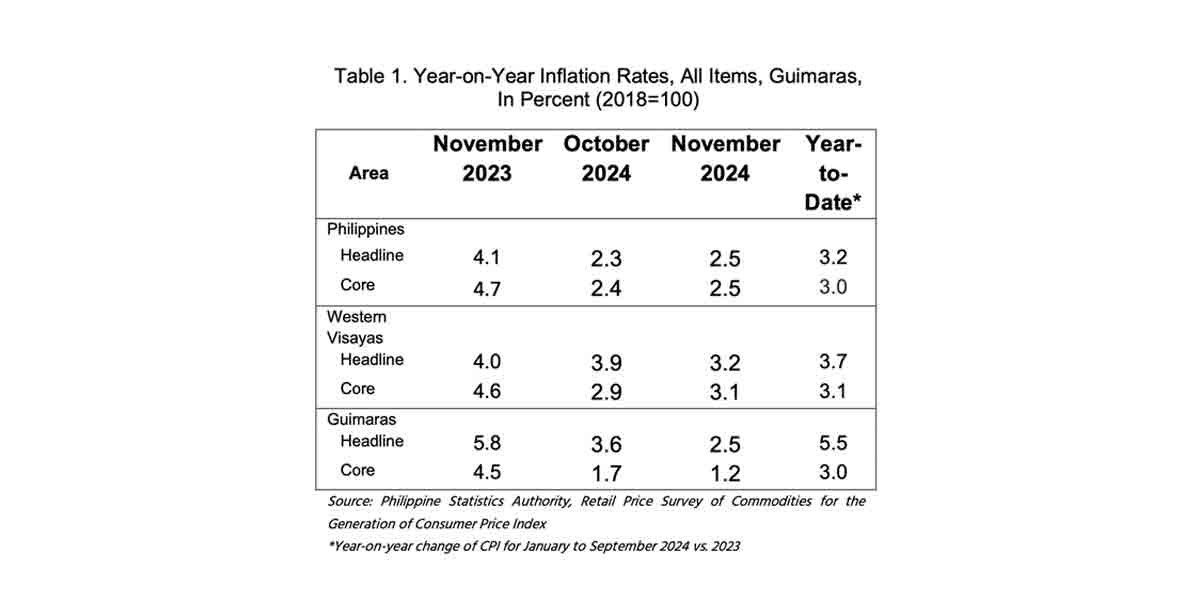

Using this definition, PCIJ research showed that over 80% of district seats in the House of Representatives are occupied by members of political dynasties.

In next year’s elections, most of them will seek reelection, while others are swapping positions with their relatives.

Of the 253 district representatives, 142 or more than half are dynasts seeking reelection, PCIJ's own count shows.

The entire province of Ilocos Norte is dominated by reelectionist dynasts, with presidential son Ferdinand “Sandro” Marcos (1st District) running for a second term and his uncle Angelo Marcos Barba (2nd District) fighting for a third term.

PCIJ's count also shows that at least 67 outgoing district representatives have opted to switch positions with family members, ensuring their political influence remains intact. Nearly half of them are term-limited.

In Las Piñas City, Sen. Cynthia Villar and her daughter, Rep. Camille Villar, are swapping places, with the former sliding back to run as a congresswoman and the latter gunning for a Senate seat.

These are two of several ways political dynasties are able to stay in power: reelection and swapping.

Underdevelopment and corruption

What's so wrong about the concentration of power in a few political families?

Studies have shown a correlation between the high concentration of political families, underdevelopment, and corruption.

A 2022 research by the Ateneo School of Government revealed that “political concentration in a province creates conditions for predatory behavior that broadens the dynast's opportunities for corruption while also limiting the ways citizens and business actors can hold them accountable.”

In places where dynasts rule, there’s less room for checks and balances, said Caritos.

“If you have families controlling the executive and controlling the legislative branch of government, there's no check and balance anymore. That's why corruption happens… why people don't get the service and the programs that they really deserve,” she said.

But political families are fighting back against criticisms. When quizzed about their families, political dynasts assert their right to run for election.

'Low supply of competent leaders'

But why do Filipinos vote them into power? It’s because of their ability to provide for their constituency through social programs and dole-outs or “ayuda,” said Teehankee.

Voters, in turn, “pay back” by casting their ballots for political dynasties, said Caritos. But she has one reminder: “Hindi naman galing sa (dynasties) ang aid na 'yan… Nanggagaling yan sa buwis natin (The aid doesn’t come from dynasties, but from our taxes).”

Teehankee also attributes the problem to a “low supply” of competent leaders.

“There’s a high demand among voters for good politics, good governance, and issue-based politics. The problem is, there’s a limited supply of such kind of politicians due to cartel, oligopoly, monopoly of dynasties,” he said.

“It’s costly for ordinary people to get into politics. And yet there’s a huge incentive for traditional politicians and dynasties to remain in power,” Teehankee added.

Renewed calls to pass anti-dynasty law

Citizens who were disgruntled by dynasties’ show of political might have renewed calls to pass an anti-dynasty law, something that the 1987 Constitution mandates.

Even Senate President Francis "Chiz" Escudero, who belongs to the powerful Escudero clan in Sorsogon, vowed not to block the passing of such a measure should the time come.

“Dahil produkto ako n’yan, hindi ko haharangin ‘yan. Kung kailangan ng boto ko para mapasa ‘yan, boboto ako dahil laban naman ‘yun sa interest ko (I’m a product of that, but I won’t block its passage. If my vote is needed for its passage, I’ll vote for it),” he said in a press conference.

But Escudero said political reform advocates should not get their hopes up. He said it has a slim chance of approval. — PCIJ.org

PCIJ’s series on political dynasties is led by PCIJ Executive Director Carmela Fonbuena. Resident Editor TJ Burgonio is co-editor.

The reportorial and research team includes Guinevere Latoza, Aaron John Baluis, Angela Ballerda, Maujeri Ann Miranda, Leanne Louise Isip, Jaime Alfonso Cabanilla, Nyah Genelle De Leon, Luis Lagman, Jorene Louise, Joss Gabriel Oliveros, and John Gabriel Yanzon.

PCIJ Resident artist Joseph Luigi Almuena produced the illustrations.