By Rhick Lars Vladimer Albay for the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

In late December 2020, an Iloilo fisherman gained online fame when a photo of him catching a humongous 20-kilo longfin trevally, locally known as lison, from the Iloilo River near the Freedom Grandstand circulated on the Internet. The same reaction was seen online in October 2021 when a video circulated of an angler struggling to reel in a 16-kilo bulgan or Asian sea bass barramundi caught along the Esplanade.

It was only a decade ago when the Iloilo River was on the brink of being “biologically dead” — so polluted that fish could hardly survive. Thanks to the efforts of the local government unit and the private sector to revitalize the waterway, the river is again teeming with marine life and biodiversity. Fish, crustaceans, and even migratory birds thrive in its brackish waters.

The first phase of what would become some 10-km Esplanade, now a tourist drawer, was opened to the public in August 2012. The banks and easements of the river that were once dotted by informal settlers and stilt houses were developed to become a walkable open community space traversing the districts of Lapaz, Lapuz, Mandurriao, Molo, and Iloilo City Proper.

The rehabilitation efforts have been successful in curbing visible pollution by installing solid waste catchments in its major tributaries. The estuarine was cleared of sunken and derelict ships that often doubled as floating informal settlements. The DENR also laid down and strictly enforced riverbank easement restrictions.

There’s still more work to do, however. Experts have been monitoring the water quality of the river, which had been fluctuating based on indices recorded.

The Iloilo River remains a drainage of domestic wastewater due to a lack of a citywide sewerage system in place. There are sporadic existing septic systems in different barangays, especially in Iloilo City Proper, but most are reportedly poorly maintained.

“Continuing monitoring of the water quality allows our office to identify trends in relation to the present plans and programs for the Iloilo River,” said Atty. Ramar Niel Pascua, regional director of the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) Region 6.

“It is evident with the results that substantial steps have already been made. However, water quality assessments also clearly present that the Iloilo River still requires further action to promote and sustain its compliance to our water quality standards,” Pascua said.

An examination of data shows that two tributary creeks in particular –– Dungon Creek and Calajunan Creek — are cause for concern.

BOD and fecal coliform levels

Twelve strategic water quality monitoring sites were established along the waterway to trace and oversee the 10-kilometer estuarine year-round.

- Muelle Loney Bridge

- Quirino-Lopez Bridge

- Forbes Bridge

- Benigno Aquino Avenue

- Carpenter’s Bridge

- So-oc Bridge

- Mouth of Dungon Creek

- Dungon V Bridge

- Calajunan Creek, Downstream Dumpsite

- Calajunan Creek, Downstream of Industries

- Calajunan Creek, Upstream

- Mambog Dam, Mambog Creek

These sites are regularly tested for chemical factors such as Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), total suspended solids (TSS), salinity, and heavy metal content, among others.

They are also tested for biological parameters such as counts of fecal coliforms, species pathogens, and viral loads.

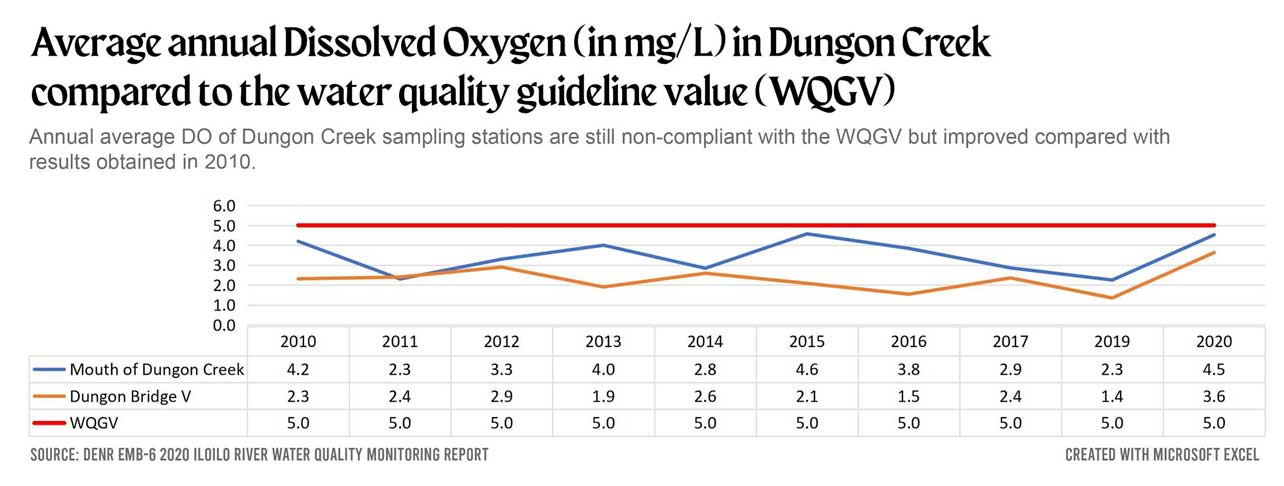

For a body of water to sustain aquatic life, the freshwater resource needs to contain at least 5 mg. of dissolved oxygen (DO) per liter of water (mg/L), based on standards of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Anything lower than 3 mg/l would cause undue stress on fish and marine species and gradually suffocate them to death.

As of 2021 all stations of the Iloilo River comply with or are very close to the minimum baseline to foster life. The 12 monitoring sites recorded a DO of 4.8 mg/L to 6.9 mg/L.

As for the BOD, which represents the amount of oxygen consumed by bacteria while they decompose organic matter in the water, the lower the better. Iloilo recorded BOD levels ranging from 1.8 mg/L to 38 mg/L during the same timeframe –– a drastic reduction from its recorded BOD of 170 mg/L back in 2010.

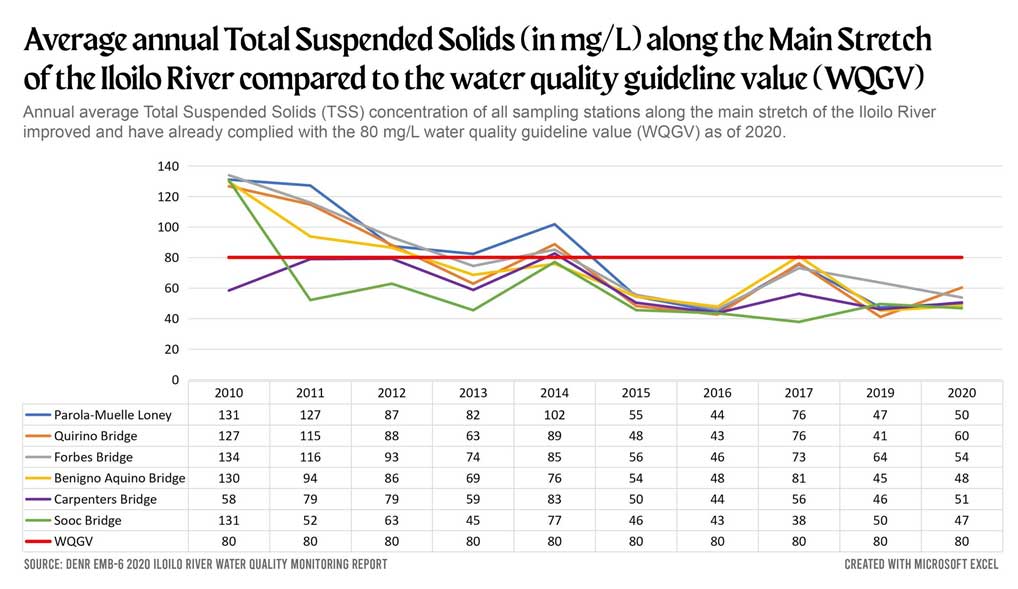

The annual average TSS concentration in all sampling stations during the same timeframe also improved and complied with the 80 mg/L baseline.

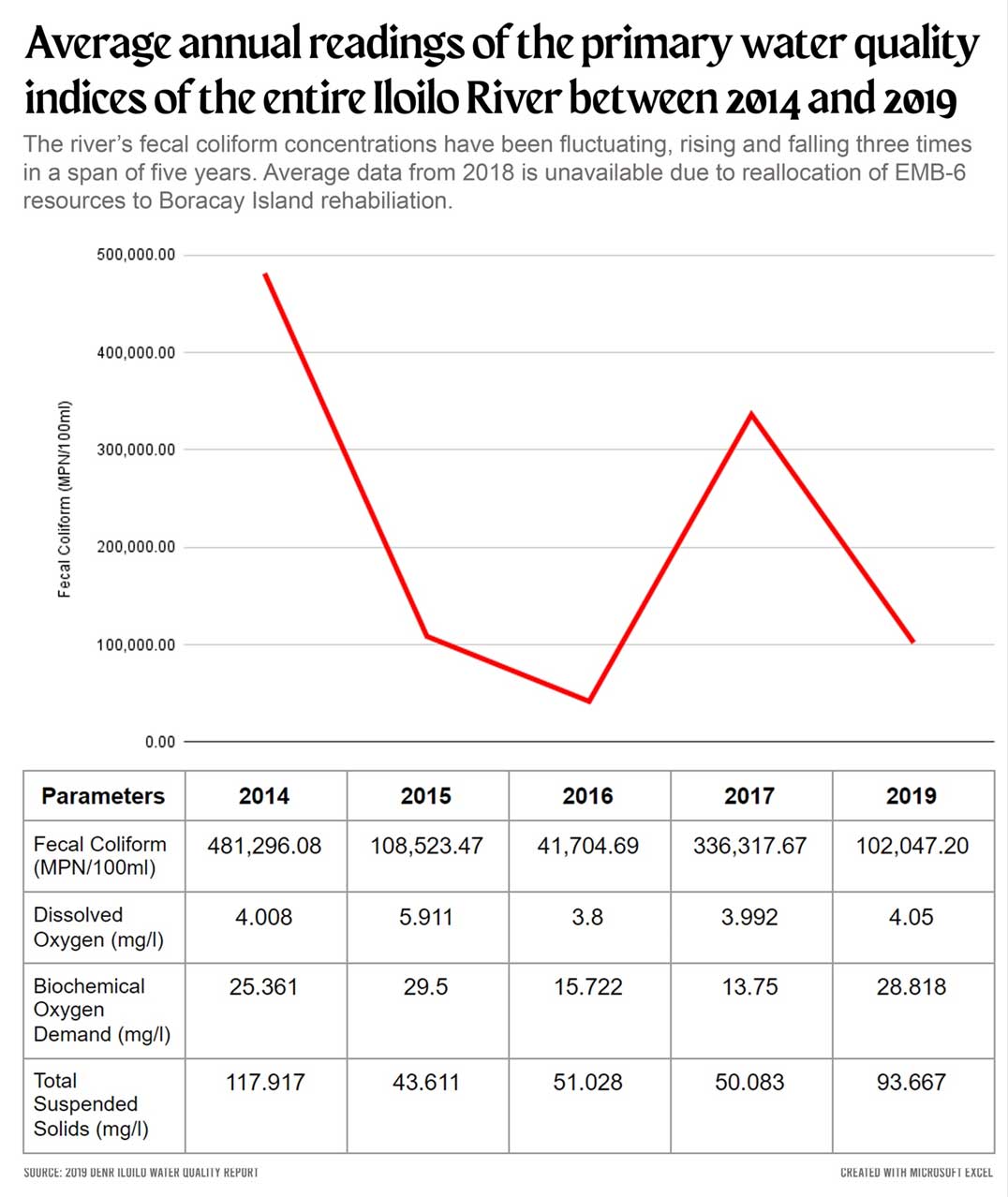

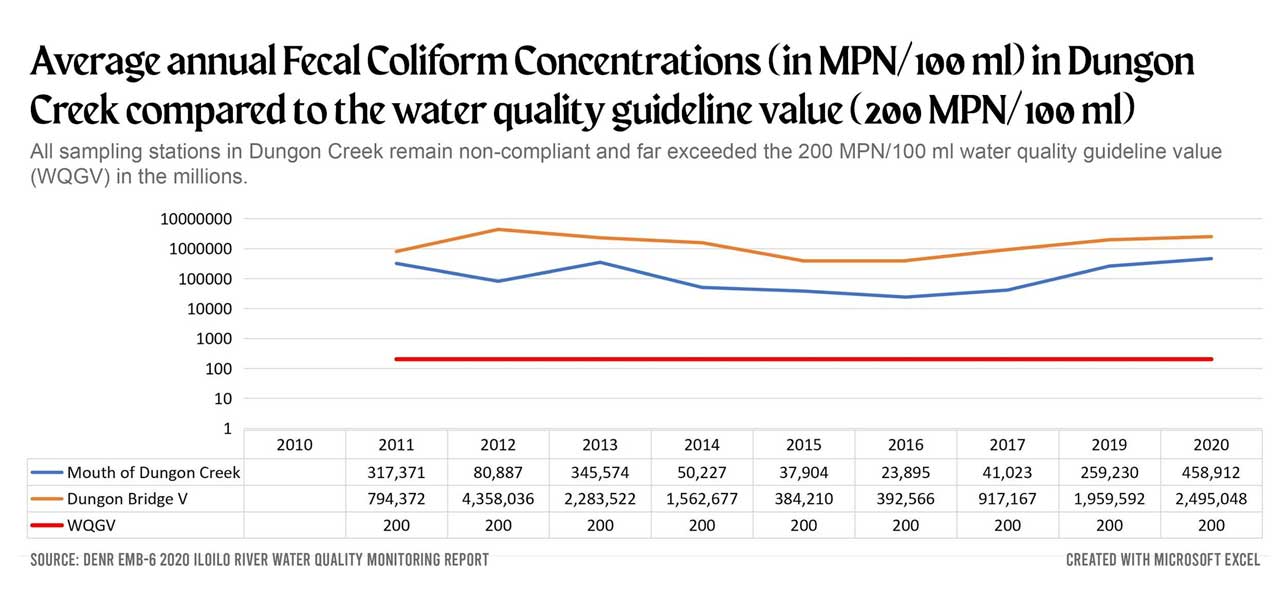

One biological parameter caused concerns, however. The Iloilo River recorded fluctuating fecal coliform concentrations, based on water quality indices published on the Iloilo-Batiano River Systems Water Quality Management Area (WQMA) Report.

Fecal Coliform indicates the presence of bacteria commonly found in the intestines of warm-blooded animals. It shows that the Iloilo River remains inundated by untreated wastewater.

The river’s fecal coliform concentrations have been fluctuating, rising and falling three times the past decade, based on the 2019 Iloilo Water Quality Report published by DENR-6.

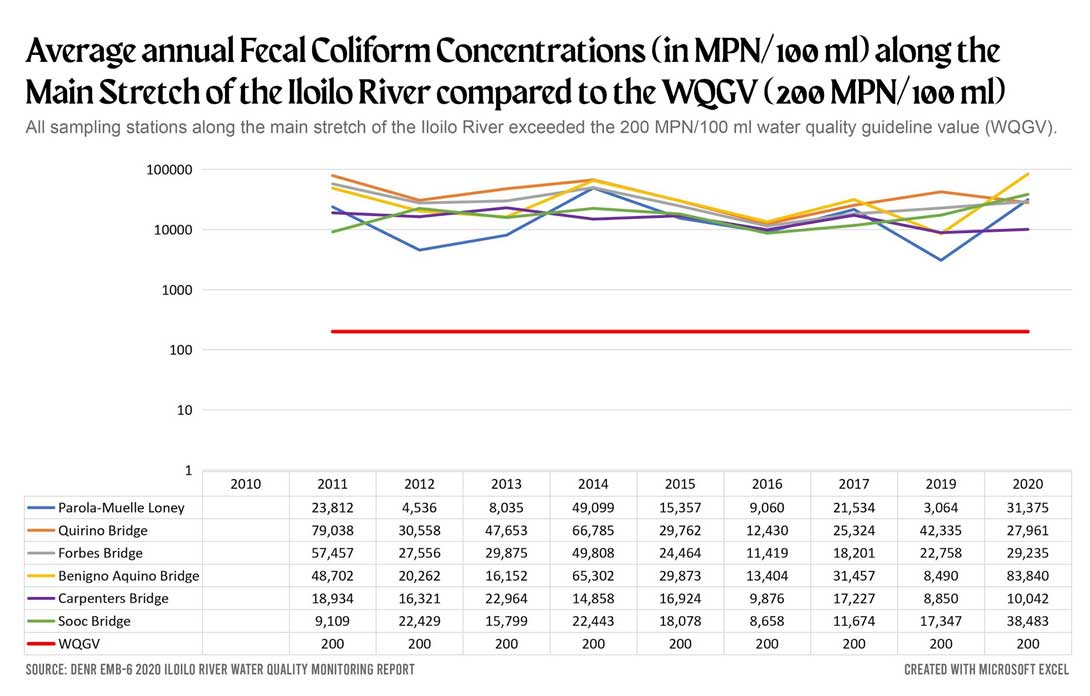

The Iloilo River recorded relatively low fecal coliform concentrations in 2021, likely due to the pandemic, recording a range of 3,181 to 653,146 MPN/100 ml although it was still above the guideline values of 200 MPN/100 ml.

The numbers the previous year showed sharp increases, ranging from 10,042 MPN/100 ml to 2,400,000 MPN/100 ml based on data from the 12 monitoring stations. It’s higher compared to 2010 despite the rehabilitation efforts, based on the latest Annual Water Quality Monitoring report.

Data from the EMB’s 2017 National Water Quality Status Report show that untreated domestic sewage is the country’s largest source of water pollution effluent at 33%, followed by commercial and industrial waste at 29%.

Out of the 421 principal rivers in the country, some 180 have been classified as severely polluted that year, while some 50 mostly urban inlets have been declared effectively biologically dead and unable to sustain life.

Iloilo River fares far better than the other urban waterways in the country. In comparison, the Manila Baywalk Area in the country capital is at nearly 100 million MPN/100ml while the Estero San Antonio de Abad, one of Pasig River’s major outfalls that empty into the Manila Bay, is at 35 million MPN/100ml.

Experts said it’s still a major concern that the revitalization has made very little headway when it comes to managing the sewage of Iloilo City.

For additional context, when Boracay was closed in 2018, the coliform level was at 47,460 MPN/100ml.

“Pollution generation of the river resulting from high fecal coliform concentrations were identified mostly from domestic, commercial, and industrial wastewater discharges, septic tanks, and backyard piggeries,” explained Pascua of the DENR EMB-6 in a statement.

The Iloilo River receives untreated sewage from 120 of 180 barangays in Iloilo City and some 50 additional barangays outside the city limits, according to Iloilo City Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO).

According to CENRO, a good number of households along the Iloilo River do not have septic tanks so all of their household and livelihood liquid wastes go directly to the water, exacerbated by the absence of facilities like public toilets and a well-maintained sewerage system.

It could have been worse. The Iloilo Batiano River Development Council (IBRDC), which led the rehabilitation efforts, believes that in its efforts to relocate some 7,000 informal settlers from along the banks of the estuarine since 2010, it has helped avoid no less than 4,000 kilograms of solid waste daily and at least 120,000 liters of untreated wastewater from entering the Iloilo River every day.

Fostering a partnership between regulators and the private sector, the council also believes it’s been integral in helping avoid 1.4 million liters of untreated sewage discharges into the Iloilo River daily.

But there are 35 barangays sitting along the banks of Iloilo River, some 75,123 Ilonggos live in barangays along the estuarine, according to the 2020 Census.

Some 10 barangays sit adjacent to the Dungon Creek alone, with a total population of 31,922 based on the 2020 Philippine census.

Focus on 2 polluted creeks

Disaggregate data from the 12 monitoring stations showed which particular areas posed concerns.

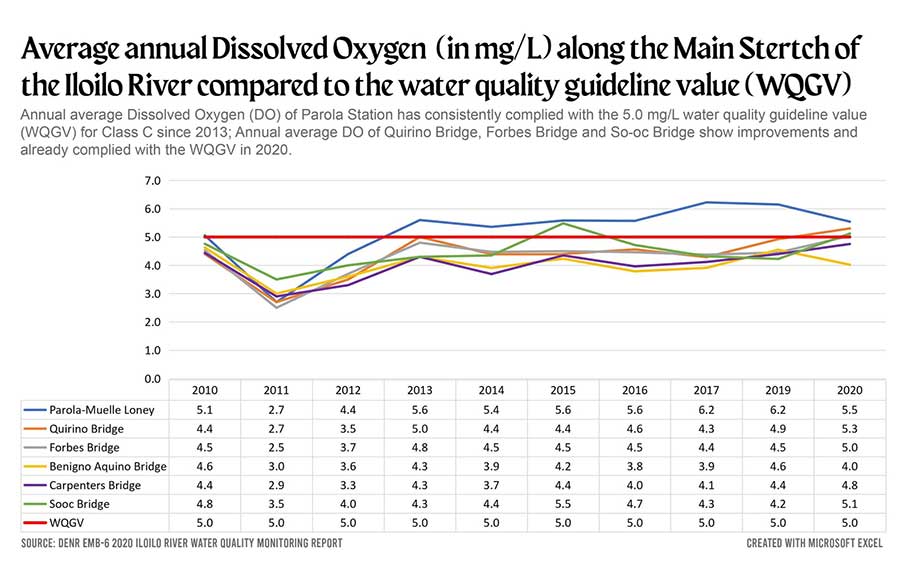

The main stretch of the Iloilo River has shown largely steady improvement – the entire stretch from Parola to Mulle Loney until the So-oc Bridge, which is covered by the six monitoring stations. The annual average DO of the Muelle Loney Bridge station has consistently complied with the 5.0 mg/L levels water quality guideline value (WQGV) for Class C bodies of water since 2013.

Meanwhile, the average DO of Quirino Bridge, Forbes Bridge, and So-oc Bridge showed improvements and already complied with the WQGV in 2020. Only Carpenters Bridge (4.8 5.0 mg/L) and Benigno Aquino Bridge (4.0 mg/L) are marginally below the threshold but they still showed consistent improvement.

When it comes to BOD and average TSS among other parameters, the annual average of all sampling stations along the main stretch of the Iloilo River have consistently complied with the water quality guideline value.

It has become increasingly apparent that, on the other end of the spectrum, the Iloilo River’s upstream tributaries are the sore spots of the rehabilitation efforts. They have been the sources of much of Iloilo River’s waste and domestic garbage, populated by residents who do not have access to septic tanks.

In a study by the Iloilo City Health Office, they estimate that the domestic sector produces some 5,625,088 kilograms BOD annually from the use of septic tanks and 588,672 kg BOD a year from open pits and latrines. Out of this, some 327,040 kg BOD per year make their way as untreated discharges into Iloilo’s waterways.

“As such, proper septage management is highly recommended to address this exceedance of discharges. Households with poor or lacking septage facilities contribute much to the fecal coliform concentrations as the Iloilo River serves as the recipient of all household discharges in the city,” DENR EMB-6’s Pascua explained.

During high tide, detritus from ocean vessels and plastic waste carried by the ocean can also intrude into the body of water.

Two tributaries have been identified as most problematic — Calajunan Creek and Dungon Creek.

Calajunan Creek absorbs all manner of products of domestic wastes, leachate from the Iloilo City garbage disposal site and sanitary landfill, as well as agricultural run-off and industrial wastes from beverage industries, piggery, fishponds, and coconut oil mills, according to a study by EMB-6.

Dungon Creek, on the other hand, absorbs discharges from fishponds, domestic waste coming from nearby residential areas and establishments along the embankment, revealed the same study. Solid wastes from households, ocean vessels, and the like similarly find their way to the river system. During high tide, the river is also vulnerable to the intrusion of wastes carried by the ocean current.

The fecal coliform levels in the two creeks had been a cause for concern. Samples on the main stretch of the Iloilo River taken in 2020 exceeded the 200 MPN/100 mL threshold, but Carpenters Bridge only recorded 10,042 MPN/100 mL while Benigno Aquino Bridge recorded 83,840 MPN/100 mL. The river’s average soared to the millions along Dungon Bridge (2,495,048 MPN/100 mL), and all the Calajunan monitoring stations (2,208,387 MPN/100 mL downstream from the Calajunan dumpsite and 1,258,230 MPN/100 mL downstream of the nearby industries).

What these two areas have in common are congested populations, murky creeks, and improper solid and water waste disposal.

“Dungeon Creek is among the underdeveloped areas of our river system. It is now being considered to be declared a ‘non-attainment area,’ in dire need of measures to counter its further degradation. Being one of the most polluted parts of the Iloilo River were taking step toward a dedicated Dungon Creek Rehabilitation Program that involves the installation of interceptors and catchments at the mouth of the tributary,” Engr. Noel Z. Hechanova, head of the City Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO), told PCIJ.

“By my own estimation, some 80 percent of the contaminants that plague our river come from informal settlements and poorly maintained poso negros, or septic tanks,” he continued.

Mangroves help

At least two factors have helped improved water quality of the Iloilo River.

One, it is an estuary river. “The Iloilo River is unique in that it’s not really a river, it’s a mouth, it’s an invagination of the sea,” said Physician and microbiologist Dr. Ian Padilla of the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV). “So cyclically, with the tide every day, seawater comes in, dilutes and washes out all the pollutants in the main stretch and flushes it out to sea. In one way it’s good because there is a continuous replenishment of the river, but in another way it’s also bad because if you have a lot of pollutants then it simply gets transferred to the coastal seawater.”

“Being an arm of the sea, during high tide, the waters of the Iloilo River flow into the Dungon and Calajunan creek and then back out again at low tide, potentially bringing with it a backwash of contaminants from these tributaries into the main stretch of the Iloilo River” explained Atty. Arjun Calvo, EMB- 6 special planning officer for the rehabilitation of Iloilo and Batiano Rivers.

Two, Iloilo City’s pockets of mangroves have contributed to improving the salient water quality along the Iloilo River since these trees feed on organic matter that would otherwise contaminate and overwhelm the waterway.

“Mangroves are very good in terms of utilizing the organic matter in the river,” Padilla explained. “They can siphon and break down larger organic material from the water. So it’s great in terms of recycling nutrients. [Mangroves] provide an ecosystem for other invertebrates and other plants to be able to grow, so they’re also very good indicators that the ecosystem is trying to recover.”

Iloilo City boasts one of, if not, the densest urban mangrove ecosystems in the country, home to some 23 of the country’s 35 endemic mangrove species belonging to nine families. In mapping spearheaded by Dr. Resurreccion Sadaba of the University of the Philippines Visayas, the aggregate area of mangroves sporadically located along the Iloilo River, Batiano River, and the coastal areas of Iloilo City totaled 132.2 hectares (an area equivalent to around 3,028 basketball courts, or a tenth of the total land of Boracay Island). Of this, some 44.566 hectares sit along the banks of the Iloilo and Batiano Rivers.

Aside from being vital in protecting shorelines from storms, flooding, and erosion, mangrove ecosystems have the ability to sequester a disproportionately high amount of carbon per unit area compared to other marine and freshwater wetland ecosystems.

A 2015 study supported by USAID and B-LEADERS concluded that the sequestration potential of mangroves in the Batiano and Iloilo Rivers totaled 194,682 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e). This total sequestration potential is equivalent to taking about 54,746 gasoline-powered cars off the road in a year, switching 8.6 million incandescent lamps to light-emitting diode bulbs, or growing more than 6.6 million tree seedlings for 10 years.

However, Iloilo-based scientist Dr. Jurgenne Primavera, chief scientific mangrove advisor of the Zoological Society of London, contends that robust water treatment solutions remain of utmost necessity to keep this valuable arm of the sea from further degradation.

“Mangroves can absorb fertilizer, nitrogen, phosphorus, and nutrients, including coliform from human settlements, from the water and use it for their growth,” she explained.

“That is why in brackish areas where mangroves thrive, the water is relatively clean. However, expecting mangroves to shoulder the entirety of the cleanup is an unrealistic band-aid solution. A genuine remedy addresses the problem at the root, it’s a public health concern, proper waste disposal and a functioning sewage system are necessary to reduce the coliform levels of the river, otherwise untreated wastewater will continue to plague our river,” she concluded.

Costly solution

The solution is clear, but it’s going to be costly. Iloilo needs a sewage system.

At the moment a majority of the city’s population predominantly relies only on private septic tanks buried onsite, these poso negros needing to be disloged or siphoned every few years by private contractors or so, or else wastewater may begin seeping into the soil if septage is ill constructed and poorly maintained.

“We do hope that there will come a time that all barangays in the city will be connected to a comprehensive sewerage system, but that will still take a lot of time and a lot of funding. Public Works is trying to craft such a city sewage plan, but no funding has been approved for it yet,” Hechanova explained, noting that nowadays the LGU’s priorities leans more towards pressing COVID-19 response needs.

“There are also some 33 water-borne diseases that can be transmitted if you swim or make contact with contaminated waters, so it is not only an environmental concern, but also a public health one,” he added.

“The construction of a dedicated sewerage system is very costly, it will entail not only the creation of a large-scale treatment plant, but also a large-scale revamp of our existing infrastructure since our drainage canals for rainfall run-off will have to be separate from our sewer lines, then, of course, the septage tanks of our establishments and homes will also have to be connected to the system,” explained Calvo.

“So imagine the laborious and painstaking process of planning and laying out this passive infrastructure on top of our existing pipes and waterlines, also finding an area for the construction of our own wastewater treatment plant. It is a mammoth challenge that entails millions if not billions in necessary funding,” he continued.

Ultimately the overall health of the Iloilo River will remain in peril if the tributaries carry on as “non-attainment zones” since wastewater from these areas can easily enter and leach into the main stretch of the river.

“That is why it is important that we also protect and conserve our creeks. All our adverse actions in these tributaries can build up and potentially cause adverse effects on the Iloilo River. If we continue to fail to clean up our own creeks, what we’ll be doing is a disservice and added burden to the Iloilo River,” Calvo concluded.