By Karol Ilagan

NARRA, PALAWAN – Teofilo Tredez knows about the ills of mining like the back of his hands. A farmer-leader and an environmental para-enforcer, he works with a nongovernment organization that has prompted the closure and suspension of at least two nickel mines in his town.

“Ang ginagawa nila ay kunin ang minerals at sirain ang kalikasan. Maiiwan sa amin ay basura, graba, kasabay ng laterite na mapupunta sa aming sakahan (What they do is get the minerals and destroy nature. What is left to us are waste, gravel, and laterite that goes to our farms),” he said on an October morning while walking along a river that was inundated by mine waste in 2012.

Tredez, 55, lives in Narra, named after the sturdy national tree, which like all towns in southern Palawan has been a host to nickel mines that threaten their farmlands and the province’s pristine natural reserves.

Citinickel Mines and Development Corp., the company found responsible for polluting waterways on top of mining in a restricted zone, was already suspended when the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) launched an audit and moved to shut its operations along with 27 other mines in 2017.

The trail of violations documented by Tredez’s group, the Palawan NGO Network Inc. (PNNI), was so compelling that the landmark audit, led by the late Environment Secretary Gina Lopez, had to affirm its findings. Five years on, the mine audit remains an unfinished business with closure orders on 15 of the 28 mines still on appeal. None of the mines ever stopped operating, however.

If it weren’t for the strong network of environmental defenders in Palawan, the infractions of Citinickel and other mines in the country’s last ecological frontier would not have been acted upon. In fact the full reports produced by the Lopez audit have not been made public up to now. Some high-ranking mining officials told PCIJ that they themselves did not see the audit.

Moreover, the project-level reports from the Mining Industry Coordinating Council (MICC) review of large-scale mines that cost taxpayers P72 million were said to be covered by executive privilege. The council entered into a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) with the mining firms whose operations were subjected to review. (See sidebar: Malacañang body signs NDAs with mining firms to keep review results confidential)

With the Duterte administration lifting the moratorium on new mining agreements and the ban on open-pit mining in 2021, environmental advocates were worried that the opaqueness of the process would worsen the already weak monitoring and regulation of mines.

Transparency advocates likewise argue that it’s all the more important to open mining to scrutiny if the government will accept new applications.

Lawyer Eirene Jhone Aguila, co-convener of the Right to Know, Right Now! (R2KRN) Coalition, said the process should even be more open so that the public would know whether the violations found in the DENR audit have been addressed.

Closure order on 15 out of 28 mines still on appeal

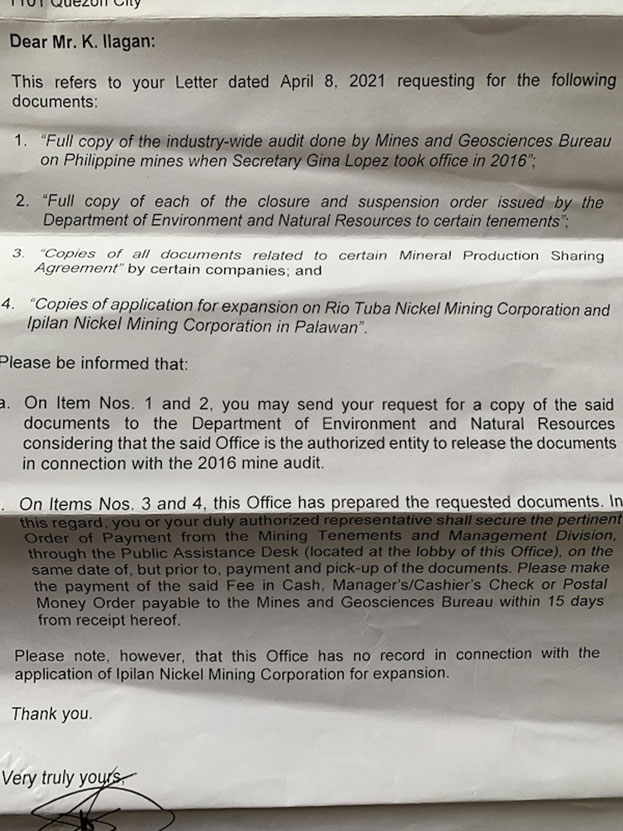

In March 2021, PCIJ requested a copy of the full audit reports for each of the 28 mines ordered suspended and closed by the DENR in 2017. The office referred PCIJ to the MGB, which referred PCIJ back to the DENR.

In a recent interview, MGB’s Marcial Mateo, chief of the Mine Safety, Environment and Social Development Division, told PCIJ that the reports were not for public use because of “pending legal issues.”

“Merong pang nag-appeal sa OP (Office of the President). Merong appeal dito sa DENR. So siguro kaya hindi pa siya pina-public ‘yung report dito sa mine audit (Some appealed before the OP [Office of the President]. Some appealed here with the DENR. So maybe that’s why they have not released the mine audit reports to the public),” Mateo said.

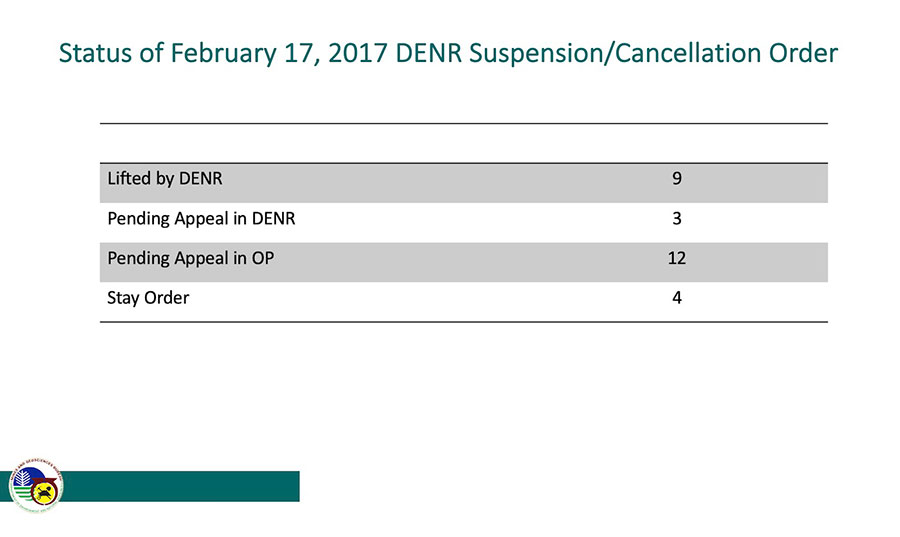

Of the 28 mines, nine had their suspension or closure orders lifted while four obtained stay orders. As of posting time, the orders issued against the remaining 15 mines were still on appeal.

Three of the 15 mines – Mt. Sinai Mining Exploration and Development Corp. in Eastern Samar, Krominco Inc. in Dinagat Islands, and Vista Buena Mining Corp./Wellex Mining Corp. also in Dinagat Islands – filed a motion for reconsideration with the DENR.

At the time of the interview in early March, Mining Tenements Management Division Chief Danilo Deleña said the MGB was drafting a memo to the DENR secretary requesting the lifting of the suspension of Mt. Sinai and Krominco.

One of Mt. Sinai’s shareholders is Vicente T. Lao, who also owns Vicente T. Lao Construction, one of the leading contractors of infrastructure projects implemented by the Department of Public Works and Highways. The company has been among the top contractors of the DPWH since the Arroyo administration, according to a PCIJ report.

Wellex Mining Corp. is owned by The Wellex Group Inc. of the Gatchalian family, whose members include Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian, who is running for a second Senate term in the May 2022 elections. Krominco’s registration papers are not available.

Twelve of the 15 mines meanwhile filed an appeal with the Office of the President. Mateo said some mines preferred to lodge their appeals before the president because they did not want to do so before the then Lopez-led DENR, which had already moved to shut their operations. PCIJ requested information on these mines. The MGB said the release of the information was still for clearance with the division concerned.

Deleña said the MGB had submitted a memo to the DENR listing the actions taken by these 12 mines in compliance with a November 2020 order of former environment secretary Roy Cimatu, the ex-general who replaced Lopez when her appointment was rejected by the Commission on Appointments in 2017. The DENR then submitted the memo to the Office of the President in October 2021, but no action has been taken yet.

PCIJ releases mine audit reports

In 2021, PCIJ obtained a copy of the full audit reports, composed of the detailed report for each company, a copy of the notices of issuance of an order, as well as the copies of the orders of cancellation and suspension.

We are releasing the reports in full here. The key audit findings and recommendations from each report were also used to update the profile of each of the 28 mines here.

It’s important to note that the audit was done in 2016, while the closure and suspension orders were issued in February 2017. Because it’s been more than five years since the audit was conducted, it’s likely that the findings in the reports have been addressed by the mining companies, especially after another review, led by the MICC, was conducted after the Lopez audit.

PCIJ wrote letters to the DENR and MGB as well as each of the 28 companies covered by the audit, informing them that we are releasing the mine audit reports. DENR through the MGB granted PCIJ’s interview request, while only three of the 28 mines gave substantial responses. The company responses as well as the supporting documents they provided were added to their profiles.

When asked for a basis for not releasing the mine audit reports while appeals were pending, Mateo could not provide a specific provision in the law. He said the companies subjected to the audit were given a copy.

Aguila of R2KRN said the audits should be considered public information. Mining companies are not under a private contract with the government, which means that typical protections such as prejudging a case or privacy, are removed, she said.

“You’re talking about privileges given by the state to you (mining firm) so and by virtue of you applying for it, you knew it could be suspended at any time. It’s not the same level as the right to life, liberty, and property of individuals,” she said.

R2KRN co-convener Jenina Joy Chavez compared the mine audits to the annual audit reports conducted by the Commission on Audit, which are made public every year on its website.

“This is an audit of mines, which the government has jurisdiction over. May findings sila na and may actions sila doon so it’s just proper na i-release ano ang results ng audit at bakit ito ang actions nila (They already have findings and actions so it’s just proper to release the audit results and why they acted this way),” she said.

Aguila said the audit team’s investigation was not a work in progress. It’s to a mining firm’s advantage to disclose audit findings so it could dispute the report publicly if the findings were inaccurate, she said.

Aguila said people in the community would know best if the findings were correct. “That’s precisely for the protection not only of the mining company, it’s for the protection of everyone who might rely on it as well,” she said.

A battery of violations

According to the MGB, the mine audit was launched to identify gaps in environmental protection measures. Unlike the MICC review whose primary goal was to recommend policy measures, the DENR mine audit could determine the appropriate penalty in case of violations of mining and environmental laws.

The audit findings for all 28 mines ranged from violations of various laws and department orders, including, among others, the Environmental Impact Statement System, Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, Philippine Mining Act, Mine Safety and Health Standards, and the Forestry Code.

Citinickel, for instance, was found to have failed to submit land use, quarterly status and production reports; failed to secure the Strategic Environmental Plan clearance; lacked a special tree-cutting permit; and lacked a designated community relations officer. It also did not fully implement the Social Development and Management Program.

Citinickel has not responded to PCIJ’s request for comment. According to news reports, the company filed an appeal before the Office of the President on March 1, 2017. The MGB said that despite the suspension, the company was allowed to ship ores after posting a surety bond.

Audit underscores weak mine monitoring

The concept of the mine audit is not new. Although an audit isn’t required for mining operations, a quarterly Multi-partite Monitoring Team (MMT) report or MMR is mandated by law. A Multi-partite Monitoring Team or the MMT is supposed to observe and measure the performance of mining operations. As an arm of the Mine Rehabilitation Fund Committee (MRFC), the MMT is supposed to be an independent body that assists the DENR in monitoring the environmental impact of mining as well as miners’ compliance with environmental laws.

The MMT reports or MMRs are submitted to the MGB as well as the local government unit for discussion with the provincial or regional development councils, especially if the mining operation is a significant contributor to the local economy.

Even before Gina Lopez’s stint at the DENR, the MMRs were made available to the public. When the Philippines became a member of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the MMRs were uploaded regularly to the Philippine EITI website.

But mining watchdogs and environmental defenders have long questioned the independence of the MMT and the integrity of the MMRs.

Jaybee Garganera, national coordinator of Alyansa Tigil Mina, said the funds used in the operations of the MMT come from the mining company being monitored, which raises questions about the integrity of the report.

Tredez, who represents the Palawan NGO Network in the MMT for Citinickel, said one of the basic problems in the monitoring is that it’s scheduled. “Scheduled, alam ng kompanya, hindi mawala ang kaugalian na napapaghandaan tuwing monitoring (the mines know, it cannot be prevented that they will be prepared every time there’s a monitoring),” he said.

Garganera said the MMR did not reflect the real situation. “Hindi na nako-cover ‘yung mga violations. Hindi nako-cover ‘yung complaints ng communities. ‘Yung hindi sapat na pagbayad ng mga taxes and revenues, wala lahat ‘yan (The violations are not covered. The complaints of the communities are not covered. The non-payment of taxes and revenues are not mentioned),” he said.

Garganera said this prompted the entry of EITI and organizations like Bantay Kita (Publish What You Pay) to improve transparency and accountability in the fiscal regime of mining operations.

In 2013, the Philippines joined the EITI, which seeks to promote transparency in the extractive industry. In its latest assessment, the Philippines received a score of 80, considered a moderate overall score, in implementing the 2019 EITI Standard. The score reflects an average of three component scores for “Stakeholder Engagement,” “Transparency,” and “Outcomes and Impact.”

The Philippines achieved a fairly low score, 68, on “Stakeholder Engagement.” The EITI board decision noted weaknesses in the engagement of some government agencies, which affected the comprehensiveness of disclosures and the follow-up of recommendations.

On the “Transparency” component, the Philippines got a moderate score of 76 points. The Philippines has made commendable efforts to strengthen data management systems for subnational transfers and payments, and to promote systematic disclosures, but the comprehensiveness of publicly available information such as licenses and contracts, beneficial owners, and government revenues should be further improved, the board decision read.

The EITI Board commended the Philippines for achieving a high score on “Outcomes and Impact,” 97 points, reflecting efforts to ensure that the EITI informs debates about nationally relevant topics, such as subnational transfers and social payments.

The MMRs did not stop nongovernmental organizations from conducting separate and independent environmental impact assessments or fact-finding missions. (See example of Friends of the Earth Japan monitoring of Rio Tuba waters and MMT reports here.)

In the same vein, DENR with Lopez at the helm was triggered to look into the real picture of how the mining companies were operating on the ground.

Lessons learned

Since the first phase of the MICC Review in 2018, relevant reforms have been instituted by the DENR and MGB through the issuance of new policy measures.

Mateo said DENR Administrative Order (DAO) 2018-19, or the “Guidelines for Additional Environmental Measures for Operating Surface Metallic Mines,” was issued to help ensure sustainable environmental conditions at every stage of the mining operation.

This order provides for the maximum disturbed area at any given time, and requires the implementation of temporary revegetation or progressive rehabilitation immediately on disturbed areas exceeding the limit.

Mateo said that because of the order, about 270 hectares were revegetated as of December 2020.

MGB likewise issued Memorandum Circular (MC) 2018-02 or the “Guidelines for Compliance Monitoring and Rating/Scorecard of Mining Permits/Contracts,” which provides a “Standard Monitoring System that ascertains the compliance of Contractors/Permittees/Permit Holders with the terms and conditions of the permit/contract and the laws, rules, and regulations.”

The MGB has instituted a Standard Monitoring System utilizing monitoring tools such as standardized checklists and scorecards to determine the level of compliance of contractors/permittees/permit holders. The plan and programs covered by the monitoring activities, especially related to safety and health, environment, and social development and management, were harmonized with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Moreover, the DENR also issued DAO 2018-20, which provides for standards in the evaluation and approval of the Work Program and ensures that mining companies adhere to environmental standards under their Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC).

This policy strengthens the Three-Year Development/Utilization Work Program (3YD/UWP) as a monitoring tool for the conduct of mining operations under mineral agreements, financial or technical assistance agreements and other mining tenements by incorporating in their program details such as: (1) temporary revegetation and progressive rehabilitation during the mining operation; (2) projected production target and schedule for each development/operating areas; and (3) disturbed area at any given time.

Teofilo Tredez, a PNNI trustee, is among many vocal environmental defenders in Palawan who have either been red-tagged or sued for oral defamation. Despite the cases filed against him, none of which prospered in court, Tredez’s work at PNNI continues.

The father of four said their work at PNNI is not done for personal reasons but for the protection of the environment, which will benefit the next generation.

“Ito ay para sa lahat – maging silang mga minero – kasama sa po rito sa gustong nating protektahan. Dahil ang kalikasan ay hindi lang para sa nagproprotekta, kundi ito ay para sa lahat (This is for everyone – including them, the miners – they are part of what we want to protect. This is because nature is not only for the defenders, this is for everybody),” he said. (END)

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN). To learn more about forest stories across the globe, visit the RIN fellows’ page here.

Rachel Ganancial of Palawan News and Elyssa Lopez, Martha Teodoro, Sofia Bernice Navarro, Ma. Cecilia Pagdanganan, and Kyla Ramos of PCIJ contributed research to this story.

Photographs: Kimberly dela Cruz and Karol Ilagan