Like many parts of Palawan, the pristinely beautiful and biodiverse town of Culion is being rezoned to pave the way for tourism development that would not bode well for the environment.

By Kenneth Roland A. Guda

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

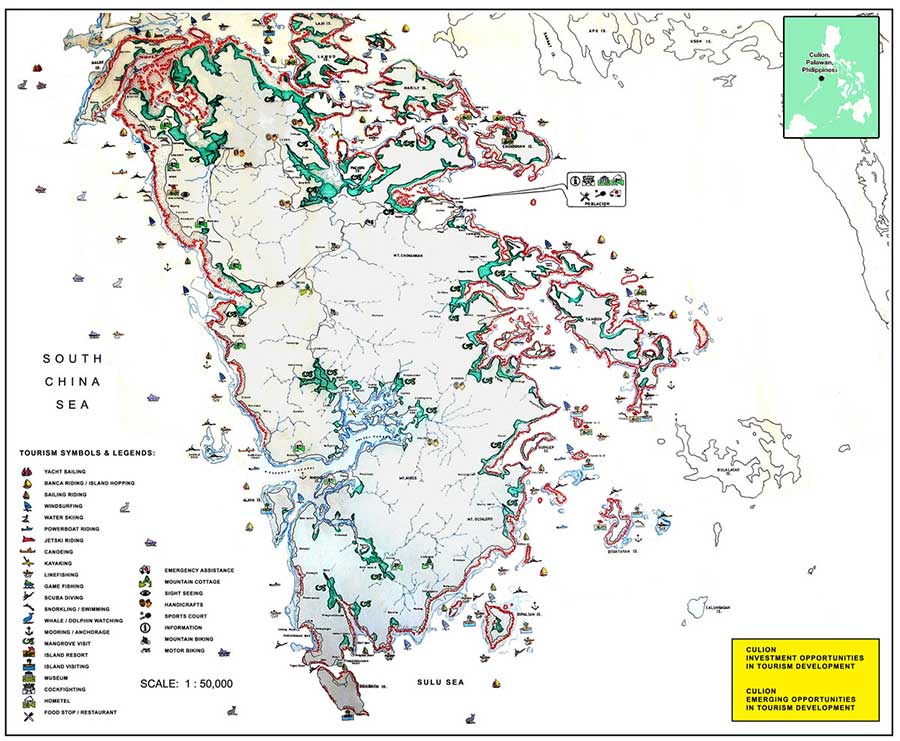

The northern Palawan municipality of Culion is on the rise as a major tourist destination.

Its neighboring town, Coron, may be more famous today. But Culion, with its 41 islands lined by pristine beaches and historical sites, is increasingly being seen as a prime location for luxury resorts, cruise ship visits, and ecotourism activities.

Much of Culion, though, is considered under the law and by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to be forest lands, critical to the survival of rare plants and animals. The town in fact is among the areas in Greater Palawan considered to be some of the most biodiverse in the world.

Endemic to the waters off its islands is the bottlenose dolphin. Native to Culion too are some of the threatened and restricted-range species of birds like the Philippine cockatoo, blue-headed racquet-tail, and the Palawan hornbill.

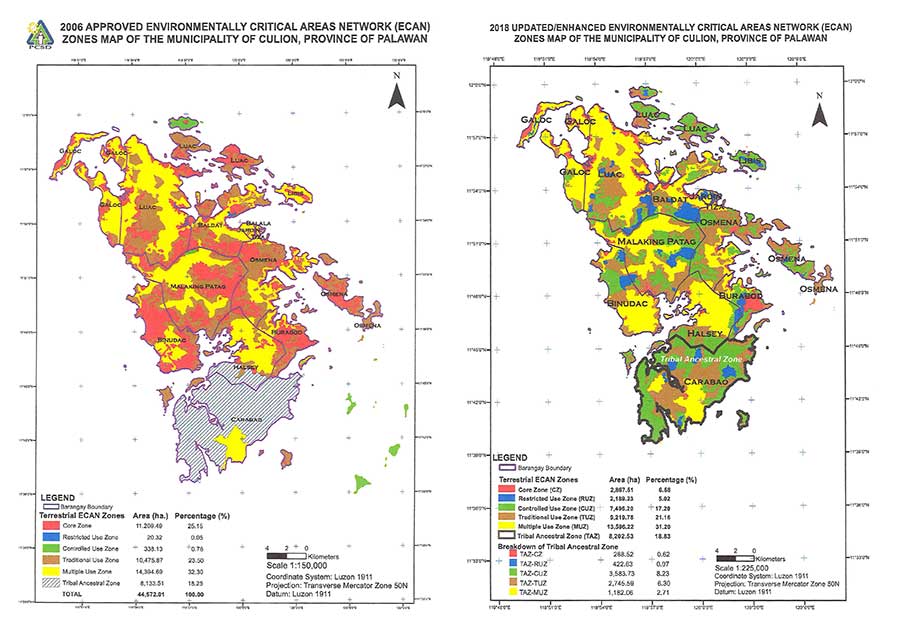

In 2006, the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), the government agency mandated by law to protect Palawan’s rich biodiversity, declared a fourth of Culion – 11,209 hectares (has.) or three times the size of the country’s capital Manila – to be “core zones” in its Environmentally Critical Areas Network (ECAN) map.

A core zone or an “area of maximum protection,” according to Republic Act (RA) 7611, or the law that created the PCSD in 1992, “shall be fully and strictly protected and maintained free of human disruption.”

The core zones are also surrounded by a “buffer zone,” an area subdivided into restricted-use zones, controlled-use zones, traditional-use zones and mixed-use zones.

Despite RA 7611, PCSD issued a resolution, also in 2006, allowing ecotourism activities in core zones and restricted-use zones, provided that it was limited to “regulated botanical tours, bird watching, picture taking, trekking, mountaineering, caving, dolphin and whale watching, swimming, scuba diving, canoeing, kayaking, boardwalking and tree climbing.”

Twelve years later, however, on Sept. 14, 2018, by virtue of Resolution 18-646, PCSD removed protections over many areas in Culion altogether. PCSD rezoned the town to shrink its core zones from three times the size of Manila to 2,868 has or three-fourths of the city.

The PCSD also converted big swaths of the buffer zone to allow restricted development and ecotourism activities. It shrunk the restricted-use zones from 20.32 hectares to 2,189 hectares and expanded the controlled-use zones from 338 hectares to 7,496 hectares. Traditional-use zones slightly shrunk from 10,476 hectares to 9,220 hectares.

Rezoning Palawan’s ECAN maps and land conversion to accommodate large-scale mining, setting up of agro-industrial plantations, or expanding tourism have also become rampant. From 2003 to 2015, Palawan lost nearly 30,000 has. of forest land, according to government data. Between 2000 and 2020, Culion’s tree cover decreased by 8.8 percent, Global Forest Watch data showed.

The PCSD resolution was issued under the chairmanship of Palawan Gov. Jose Alvarez, a timber tycoon before he and his family entered politics.

He owns a long list of properties and businesses in and out of Palawan and was the richest elected official in the country, with a reported net worth of P4.67 billion, as of 2017, when asset records of local government officials were publicly available.

He remained as chair of PCSD as of this writing, following a successful bid for a third and last term in 2019.

The case of Naglayan Island

One of the 41 islands rezoned was the 18-hectare (ha.) Naglayan Island. Located in the northern part of Culion, on the east of Marily Island.

It was a traditional-use zone in 2006. In 2018, it became a multiple-use zone, where, according to RA 7611 or the ECAN law, “landscape has been modified for different forms of land use such as intensive timber extraction, grazing and pastures, agriculture and infrastructure development.”

But mangrove trees used to cover Naglayan’s shores, while a thick canopy of various trees covered most of the island.

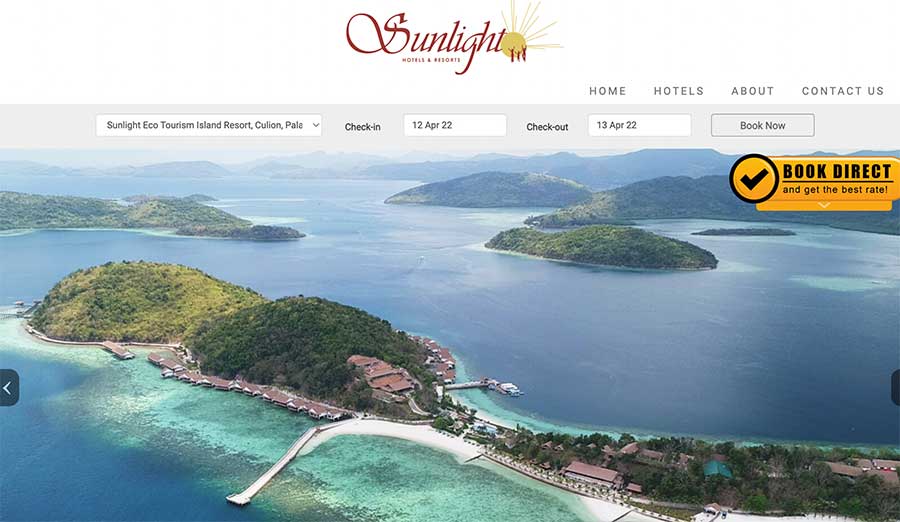

Even before the rezoning of Culion, in 2012, Sunlight International Island Resort Inc. began developing Naglayan into a luxury resort.

Developers cut mangrove trees and poured in white sand from other parts of Palawan on its shores. Lumber from other parts of northern Palawan were reportedly brought in as material to construct “Maldivian” beach cottages and other resort structures, according to authorities. This included a long bridge to an elevated bar above the waters where there used to be mangroves.

When the resort opened, the island was christened “Sunlight Eco-Tourism Island Resort.”

In April 2015, a team of law enforcers raided the resort based on two search warrants from the Palawan Regional Trial Court. The team, headed by the Palawan provincial government, joined by PCSD, local police and DENR personnel, found more than 100,000 board feet of lumber in the resort’s stockyard.

Sunlight was forced to close its operations, but was able to resume after four years, in 2019.

On Jan. 28, 2019, the PCSD came out with Resolution 19-661, announcing its decision authorizing Governor Alvarez to enter into a compromise agreement with Sunlight. PCSD agreed to drop the cases it had filed against the developer in exchange for a P250-million settlement from the resort.

PCSD viewed the compromise agreement as “an undertaking that will aid in financing the rehabilitation and restoration of Palawan’s environment and to support the enforcement and monitoring activities of the PCSD and other agency-partners, relevant organizations and institutions through Memorandum of Agreement or Undertaking that would later be entered into by the PCSD with the Provincial Government of Palawan.”

According to the resolution, Sunlight offered P250 million to PCSD to settle its liability for violating environmental laws. It also stated that Sunlight had deposited P100 million as initial payment to the provincial treasurer of Palawan.

However, PCSD claimed that the amount was in fact deposited to the National Treasury. In a letter received by PCIJ on April 27, 2022, it said the first payment was made on Oct. 19, 2017, or 15 months before the actual settlement.

Since then, the developer had paid in installments. Three years after the agreement, Sunlight had so far only paid P123,333,333.32 or less than half of the agreed amount for the settlement.

Protests

Civil society groups have raised questions about the compromise agreement. In an interview with PCIJ, Grizelda Mayo-Anda, environmental lawyer and executive director of Environmental Legal Assistance Center (ELAC), said there was no clear scientific basis to determine if the P250 million was enough to address the environmental destruction wrought by Sunlight.

“There should have been a scientific assessment of the wood that was confiscated and the forest where the wood came from. Otherwise you would not give appropriate value to the resource [lost],” said Anda.

Chan believes that whatever Sunlight was made to pay, it should not have been in the form of a settlement.

“It should be in the form of a penalty. After they have been penalized, they should not be allowed to operate. It is an embarrassment to Palawan that [PCSD] seems to say that we cannot penalize big establishments because they are financially capable of litigating,” Chan said.

According to Sunlight’s 2019 financial statements, the company had P27,557,010 in current assets in 2019 and P13,674,270 in 2018. This was below the P250-million settlement it supposedly paid to PCSD in 2019. The settlement was also not reflected in the company’s 2019 financial statements, the latest available documents as of this writing.

Sunlight did report P501.13 million in non-current assets, but this covered land, building, furniture, equipment, and vehicles. Current assets refer to cash on hand or in bank and other liquid assets. The company reported a net loss of P112,151,434 in 2019, wider than the P16-million loss incurred the previous year.

Sunlight resumed operations only a few days after PCSD signed the compromise agreement. It even invited celebrities to its opening and had a string of influencers to promote the luxury resort on social media.

Sunlight continued operations even amid the Covid-19 lockdowns, ferrying clients from Luzon to Culion via its own newly launched luxury airline, Sunlight Air. Sunlight also hosted celebrity weddings like that of model Jessica Wilson and investment banker Moritz Gastl in June 2021.

Questionable titles

In a June 2021 interview with the PCIJ, Eriberto Saños, then Palawan’s provincial environment and natural resources officer or Penro, said Naglayan was a “forest land” or “timber land,” and therefore inalienable. But Sunlight’s owner, a Chinese businessman named Giok Brito, claimed to own two titles to properties on the island, one of them issued in 1972.

Saños said the titles were possibly fake on the basis that the islands of Culion were forest lands and not subject to titling or individual ownership. Anybody claiming they own these islands must have faked the titles, he said.

Sunlight’s 2020 general information sheet lists a certain Ricardo Brito as president and chairman of the board. There were four other shareholders. Sunlight registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2012 “to engage in the business of establishment and operation of resorts, hotels, and other related activities.”

In October 2021, PCIJ also sought an interview with Alvarez, who chairs the PCSD. Alvarez forwarded the request to the council staff.

Teodoro Jose Matta, a lawyer who serves as PCSD executive director, told PCIJ in November 2021 that he agreed with the assessment of the Penro. “What we did in the legal office (of PCSD) then was to endorse it to the Land Management Bureau, lock stock and barrel, and ask for the nullification of [Brito’s] titles,” he said.

For his part, Saños said his office submitted to the DENR Mimaropa regional office in 2015 a certification that Naglayan is forest land, recommending that the titles be nullified and that the Solicitor General pursue a case against the resort developer.

However, on July 29, 2021, in an answer to a request from PCIJ asking for documents on the cases filed against Sunlight, the Office of Solicitor General (OSG) said “it appears that the DENR has not endorsed any concern relating to the above-stated cases to the OSG.”

On March 9, 2022, PCIJ sought an interview with Sunlight management via messaging app Viber. A company staff acknowledged PCIJ’s messages and provided the company’s email address, where PCIJ sent a letter. We made follow-ups on March 18, April 4, and April 6. We have not received a response as of this writing.

Strangers in their own land

Naglayan was just one of the first islands in Culion to be developed into a resort.

According to John Lisboa, former member of Municipal Tourism Council of Culion and now an environmental advocate for his town, the sale and development of island properties have only intensified in recent months.

“Aside from historical attractions, Culion has a lot of natural attractions. There are waterfalls, white sand beaches, hikable mountains. But many of these properties have now been owned by foreigners. We noticed this when tourists began flocking here in recent years,” Lisboa said.

“We gradually became strangers in our own land. Before we could do picnics in any area for free. Now accessing these areas for locals can be difficult,” he added.

Real estate websites have also been featuring many islands and beachfront properties in Culion for sale. Among them: Dipalian Island, a 153-ha. island property south of Culion Island, for sale for P550 million; Calumbagan Island, also south of Culion, for sale for P688 million; a 168-ha. beachfront property in Culion Island for sale for P505 million; a 12-ha. beachfront property in Galoc in Culion Island; and many more.

In January 2020, Palawan News reported that Tagbanua indigenous people residing on the 588-ha. Lamud Island, north of Culion Island, complained that a company named Almavida Holdings had put up barbed-wire fences around the island to keep them away from their houses.

The residents were able to stop the fencing after local DENR and National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) personnel came to Lamud to investigate.

“A former barangay captain, and a few others, sold his land in Lamud (to Almavida). They did not have titles, only tax declarations. When Culion was a leper colony [during the first half of 20th century], people could apply for pasture lands to supply food for the colony. But they did not own the lands,” said Fr. Roderick Caabay, former parish priest of Culion and an advocate for the town’s indigenous people, in an interview with PCIJ.

“About two years ago, our parish became involved with protecting the Tagbanua residents. They were already complaining that their lands were being taken away from them,” he added.

Lisboa said a similar thing happened a few years ago in Inanda Island, south of Marily Island and west of Naglayan. The owner allegedly built pathways within the entire island. “The owner even asked us where he can buy white sand,” he said.

Saños said they were aware that many forest lands in Culion were being bought and developed for various purposes, including tourism. In the case of Sunlight, officials could only recommend prosecution, he said.

That case also showed how local DENR officials depended on the cooperation of various national and local government agencies such as the Office of the Solicitor General, or PCSD and the local governments of Palawan and Culion to protect Culion from environmental ruin.

When you’re the most powerful on the island

PCSD’s Matta defended the rezoning of Culion’s core zones and buffer zones. Although it was the government’s mandate to protect the environment, he said it also needed to balance environmental concerns with economic considerations.

“Palawan Council for Sustainable Development – it’s not just mere conservation. We’re talking about sustainable development. And what does that entail? It entails the balancing of interests, including economic, including social, and including environmental. And unfortunately, right now, all these things have to be taken together as a whole,” he said.

The Alvarezes, a powerful political clan in Palawan, have been pushing for this kind of development in Culion. In 2021, Governor Alvarez pushed for the construction of the Coron-Culion Inter-Island Bridges before it was shut down. Concerned groups like the Palawan NGO Network Inc. protested, saying the project would affect 300 has. of coral reefs and 150 has. of mangrove forests in the area.

“The bridge is obviously aimed to cater to tourism development in Culion,” said Lisboa.

In Congress, Governor Alvarez’s nephew, Rep. Franz Josef Alvarez, co-sponsored in 2019 a House bill declaring Palawan a “Priority Cruise Ship Destination” and providing government support.

In 2021, Representative Alvarez filed a bill expanding the Busuanga airport to facilitate tourist travel to the Calamianes islands, including Culion’s 41 islands.

Franz Alvarez is in his third and final term as representative of Palawan’s first district in the House of Representatives. His father Antonio Alvarez, the governor’s brother and who used to hold the same office, is seeking to return to his old seat.

Antonio reportedly owns Maremegmeg Beach Club, a high-end resort in El Nido, Palawan that is managed by his other son, Diego.

Governor Alvarez is on his third and last term in the Capitol. He earlier spearheaded a proposal to divide Palawan into three separate provinces, but it failed when almost 59 percent of voters rejected it in a plebiscite in March 2021.

“[The plebiscite] was a way to divide Palawan into smaller, manageable parts so that the extraction of resources would be more efficient,” said Robert Chan, environmental lawyer and executive director of Palawan NGO Network, Inc. (PNNI), in an interview with Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ).

“If you divide it into three, and you have three [governors] with utilitarian minds managing it, they would be more efficient in utilizing resources, and we don’t want that,” he said.

The governor’s daughter, Amy Roa Alvarez, has been municipal mayor of San Vicente, Palawan since 2019. Another daughter, Maria Carmela E. Alvarez, was the three-term mayor of San Vicente prior to her sister’s election. Carmela disclosed in her 2017 wealth declaration that she was a stockholder of Club Agutaya, a resort hotel in San Vicente.

Governor Alvarez’s son, Pedro, was also a municipal mayor in Baungon, Bukidnon.

The proposals being pushed by the Alvarezes concerned Lisboa, who said that in Culion, environmental protection often took a back seat in favor of commerce and tourism.

“We believe in responsible and disciplined tourism. The problem, it seems, is that there is no systematic implementation of the laws regarding the protection of the environment,” he said. END

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN). To learn more about forest stories across the globe, visit the RIN fellows’ page here.

Infographics: Joseph Luigi Almuena

Photograph: Aerial shot of port and town in Culion, Palawan, taken in November 2019. Image by MDV Edwards/Shutterstock.