By Keejoon Shin

The modest potato is an integral part of hundreds of international cuisines. Annual production is close to 92 million metric tonnes, while more than one billion people worldwide consume potatoes daily, according to the International Potato Centre in Lima, Peru. It is the third-biggest agricultural product worldwide in terms of human consumption, after wheat and rice.

By 2026, it is anticipated that Filipinos will consume 307,000 metric tonnes of potatoes, while more than 122,000 metric tonnes will be produced in the same period.

Given how heavily the crop is relied upon globally, I believe it is crucial to safeguard and improve its safe production for both present and future generations. Consequently, virus-free potato crops are a necessity.

When compared to other crops like wheat, soybeans and corn, potatoes are unique. They cannot be stored for extended periods, due to their high water content. Additionally, when transported, potatoes tend to carry the soil from which they were cultivated. Since transporting soil over international borders is heavily regulated and quarantined, the majority of crops tend to be cultivated and consumed locally. Since there are no commodity or futures markets for potatoes, no global corporations are involved in the industry. In other words, the market is extremely difficult and fragmented. And that’s before we even mention viruses!

Aphids

Potato viruses are primarily transmitted by aphids that feed on plant sap, such as greenflies and blackflies. Over one hundred viruses can be spread to a variety of plants by the green peach aphid alone. The potato plant is infected by the potato leaf roll virus, which is carried in the aphid’s intestines. These viruses are notoriously challenging to get rid of since they are so quickly spread. It’s one thing to get rid of aphids from a typical houseplant, but quite another to eradicate them from a whole crop.

Making sure there is enough space between each plant, and treating the crop with a fungicide before blight makes its unwanted debut are two current strategies for preventing illnesses. To stop a disease from spreading in the soil, some farmers choose to rotate their crops. Another strategy is to remove and destroy both the tuber and the plant when blight occurs.

It may be known to those familiar with European history that blight is one cause of the potato famine in Ireland in the 1840s. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, when blight was better understood, that measures were adopted to stop it from harming upcoming crops.

Virus-free is possible

Recently, a micro tuber the size of a soybean was used to produce a potato seed devoid of viruses. Created in a lab under strictly controlled conditions, it weighs around one gram and can be mass-produced. All year long, unlimited copying is also feasible. A potato plant has a life cycle of roughly six years, but micro tubers dramatically shorten this to between one and two years. The resultant reduction in the chance of the crop becoming infected with a virus and the consumption of resources including water, fertiliser, pesticides, and electricity.

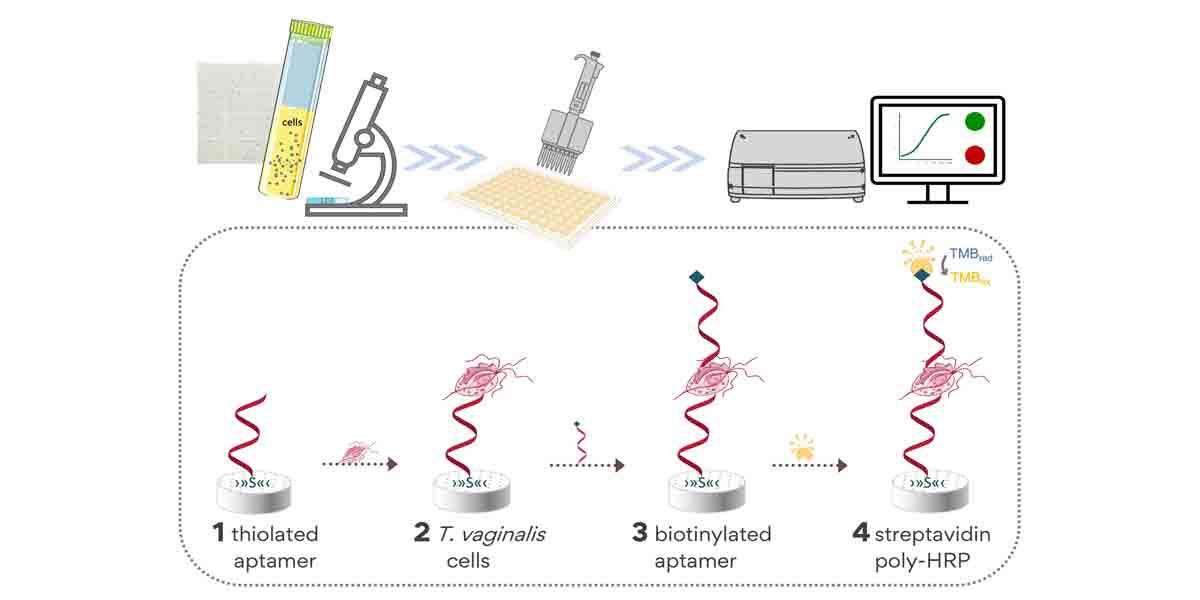

The process itself involves procuring virus-free stems, propagating these stems, inducing tuber formation and subsequently harvesting micro tubers.

To prevent illness from spreading through successive generations of crops, seed potatoes must be virus-free. Only about 10 to 15 of the world’s potato-growing nations have a mechanism in place to apply this technique; the remainder continue to use seed potatoes that have been contaminated with viruses.

I think that each region has two possibilities for moving forward: grow the virus-free seed locally or import it. Due to the numerous limitations and problems related to trading and cultivation methods I stated above, the latter is feasible but very constrained in volume.

The bulk of us likely think of Africa when we consider those parts of the world that are most affected by poverty. Only around 5% of crops there are high-quality seed; this can be boosted to between 30 and 40% with microtubers. As a result of an improved potato crop, local farmers would benefit from a higher percentage of high-quality seed and will see a rise in revenue across the entire region. The potential of this in the fight against world hunger is enormous. The World Food Programme (WFP) believes that over the previous three years, the number of people experiencing food insecurity has increased by an alarming 200 million. COVID-19 and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine crisis have only contributed to this increase.

The importance of potato crops free of viruses and with higher yields has never been greater. I believe this is where we should start if the millions of people currently going hungry and malnourished around the world are going to survive. The modest potato might well be the one to save the globe.

Keejoon Shin is the Founder and CEO of E Green Global. Headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, the company aims to utilize its unique micro tuber technology in the worldwide fight against hunger and poverty. www.eggtuber.com for more information.

E Green Global is an agritech firm aiming to eliminate harmful viruses from potato crops worldwide. These diseases have been present in a majority of potato varieties for generations, and have long been considered unavoidable and a cost of doing business. EGG’s “microtubing” method has been developed over several years, and has the potential to significantly and permanently increase the yield of potato farms, and as such has the potential to have a major impact on poverty and hunger. For further information please visit https://www.eggtuber.com/.