By John Anthony S. Estolloso

FACES HOLD a special appeal in art; portraiture after all is a revered genre among visual artists and many a painter’s skill was put to test by his or her capacity to capture the likeness of the model’s facial features or the dramatic portrayal of these to convey some sort of emotional or cultural nuance. Hence, the blatant removal – or the recurring multiplicity of faces, in the cut of van Gogh’s or Kahlo’s continuous projections of their selves – in art hold profound meanings, deeply introspective or communally shared these may be. It is with this sentiment that the writer explores Mark Rene Nativo’s new collection of artworks.

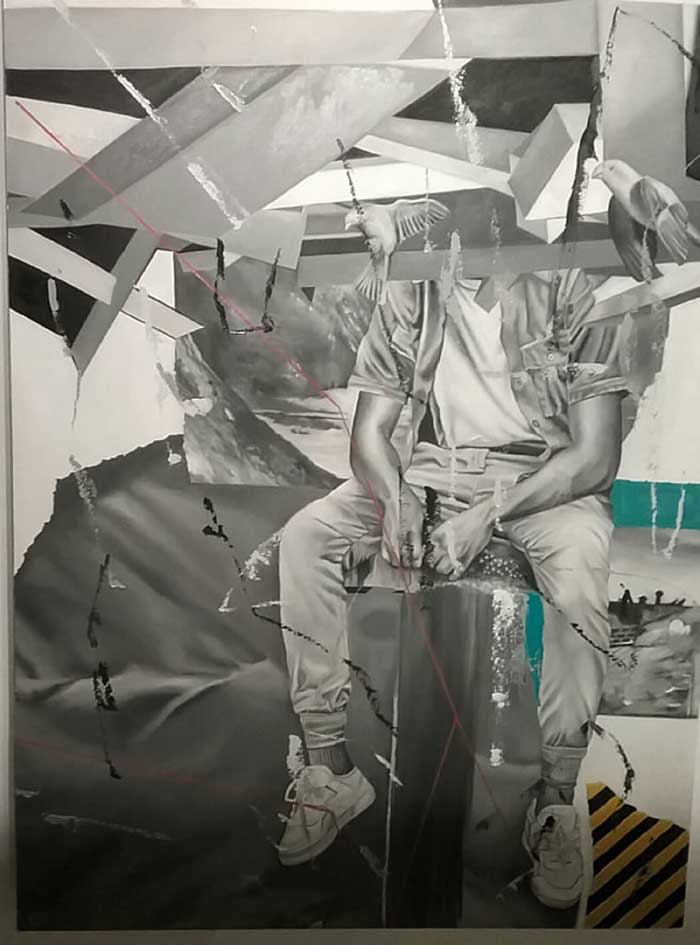

Last September 6 saw the opening of his latest exhibit of canvases at MAMUSA’s loft. It was a lean evening: few canvases witnessed by fewer audience who permeated the atmosphere with subdued conversations of the painter’s artistic process. But what was lost to the public in that vernissage was more than made up by the figurations embedded in the paintings: far from the conventional of Nativo’s art is the erasure of faces found in these uncurbed intersections.

For if one is to look back to the trademark style that Nativo’s artworks were usually associated, hyperrealist portraiture comes to mind immediately: wide stretches of canvas with carefully rendered faces of notable characters from history (I can recall Dali and Chaplin) sprawled in monochrome, with an occasional splotch of bright colors as accenting contrasts.

Not anymore in these uncurbed intersections: gone are the looming visages overwhelming the viewer with their piercing stares. In lieu of these faces are surreal abstractions in carefully controlled palettes set in his usual monochromes, with the occasional full figure of personas passing through this decoupage of lines and geometric figures. What is striking is how the faces of these personas were intentionally blotted or blocked, as if a deliberate obliteration of identities mirroring a projection of an unsure yet conscious exploration of the artist’s self – or at least, his experiences.

In conversation with the artist, Nativo reveals his process: some of the canvases were finished just a week prior the exhibit and while on display, the newly dried paint is still somehow discernible. Mostly rendered in solitude, these canvases capture his sentiments of the experiences shared with his son, more so that these subtly mirror his juvenile fears and anxieties. Projected through dream-like iconography and overlapping shapes and colors, they have become a journal-like though charmingly aesthetic documentation of the artist as paterfamilias.

But to the eyes of the discerning viewer, these abstractions seem to invite more questioning rather than criticism. Would the erasure of faces bespeak of this erasure of identities, thus leading the spotlight on the universality of the art’s subjects? Or must we construe an intentional forgetting that is projected through the facelessness of his subjects? Is the jagged brokenness of the geometric figures that bisect or cut through the faces evocative of a more personal brokenness that finds a certain modicum of catharsis in the making of the artwork?

Or take the unusual reference to surreal impressionism that surfaced in his canvases. Would the personas in broken cages of lines and colors reflect the yearning of the artist to break new ground in his art? Are the birds coursing through these intersections an attempt to chart a course through the artist’s unsure flights of fancy? Or are these reinforcing configurations that the artworld’s conservative context where the art is expected to thrive is still king and the artist must toe the line somewhere? Do all these mirror the artist’s struggle in attempting to navigate through these stranger artistic tides?

Relatively, these canvases are new, if not disorienting, experiences to the viewer comfortable with Nativo’s customary style. As to how the Ilonggo audience will receive this latest batch of his works remains to be seen. He can stay in the monochromatic realm iconic of his usual work – or he can burst out uncurbed from his usual run of shades of gray and find new vibrance in bright colors and unconventional imagery albeit the loss of identities among his figures.

Uncurbed Intersections will be on exhibit until October 3 at MAMUSA.

[The writer is the Subject Area Coordinator for Social Studies in one of the private schools of the city.]