By John Anthony S. Estolloso

TO SAY that the city is a mere composite of entities would be an understatement of what were projected within the frames of Mark Vincent Java’s panoramas and the assemblages of Cristhom ‘Dodoy’ Setubal. Last January 10, the lobby of Days Hotel at the Atrium played host to the opening of a collaborative exhibit of the works of these two artists, bringing to the consciousness of the viewers a fresh look at the city as a shared space.

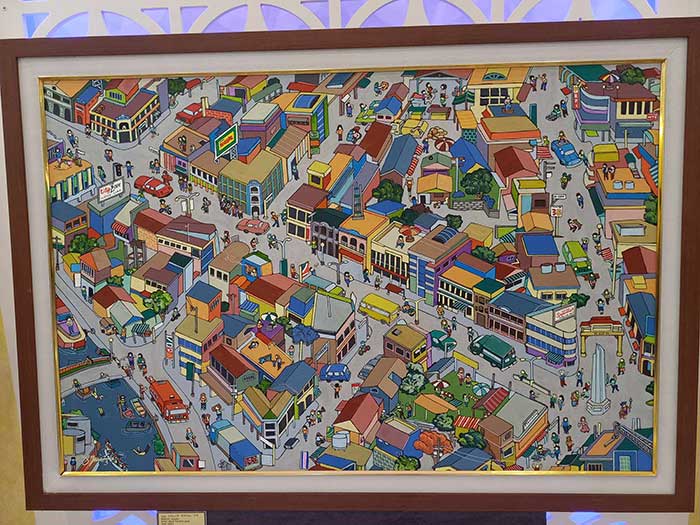

Mark Vincent Java’s style of panoramic depictions of local mise-en-scènes of Iloilo City is readily recognizable by most art connoisseurs of the region. While its intention is to capture the scenarios and the denizens that congregate through its hubs, his canvases likewise ‘freeze the present’, thus fulfilling an essential function of art: to hold up a mirror, reflect, and preserve for posterity, the zeitgeist of the artist and his contemporaneity.

Peer closely at his panoramas and you start to identify the routinary details that give life to the city: the street vendors hawking their afternoon supply of fishballs and tempura, the frozen figures that would have gyrated in Zumba exercises at the plazas, the early morning joggers oblivious to sun or smoke, the tricycles idly parked and waiting for passengers, and the ever-ubiquitous pedestrians strolling through the busy sidewalks and crisscrossing thoroughfares.

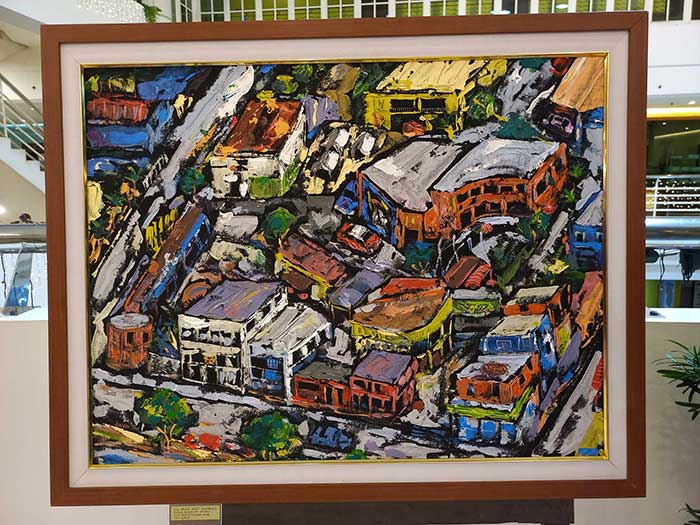

While patrons of Java’s work are acquainted with his usual panoramic projections – a Larry Alcala vibe sans the comic – the exhibit likewise introduced viewers to a shift in style: new to the audience and transcending the two-dimensional panoramas are impressionist renditions of similar urbanscapes. Through the hazy daubs of colors and the barely discernible figures of buildings and people, one senses the frenetic hustle and bustle of city life, the homely urbanity that the city-bred Ilonggo is most familiar with.

As Java’s art attempt to capture the current Ilonggo spirit of our time, Dodoy Setubal’s assemblages on the other hand attempt to recreate the iconic images that, perhaps for some of us, have been around long before even we were born: it is indeed an urban rendezvous of the historical and the contemporary.

Even as Setubal’s exhibit of Panayanon churches sits stolidly at the National Museum just some few hundred meters away from his current collection, his display of the landmarks of Iloilo City retains the same authenticity of upcycling from odd bits and ends of castoff material.

Set on veneered planks of wood are the icons encountered in the public spaces of the city: the regal tower of Arevalo’s plaza with its ostentatious crown, the silent caryatids of Arroyo fountain standing upon their base of crustaceans, the sprawling Aduana with its simple yet well-defined lines, and the several heritage houses that dot certain sections of the city are reimagined through pieces of plastic and metal, cardboard and wire.

One senses some irony in the hodgepodge and the bricolage: the elevation of discarded and ordinary materials into representations of the monuments that have become the city’s metaphors. In a sense, the simplest and humblest of things ‘make sense’ of the grandest of our public structures, a subtle suggestion perhaps that what truly defines Iloilo City lies not so much on the grand and great but on the constant and low-key conventionalities of the Ilonggo lifestyle.

Though we can readily say, at first glance, that the artists’ works escape the scrutiny of weighty interpretation, they nonetheless invite the viewer to look closely at the elements and details that build up the whole and immerse in the kaleidoscopic structuring of colors, lines, and materiel. To critique art after all does not lend itself only to interpretation: it likewise necessitates description and evaluation, and if these suffice, then the value – or our understanding – of the artworks would not have been diminished at all.

In both collections, the mundane becomes extraordinary: whether projected as panorama or assemblage, the images identified with Iloilo City are reiterated as narratological artifacts, talking about the present and retelling what was past. After all, where else can the past truly meet the present than in the many iterations of art?

[The writer is the subject area coordinator for Social Studies in one of the private schools of the city; the photos are from Israh Dayalo and are used with permission.]