Filipino music, in general, was introduced to me by my wife, Rossana. What does music mean to Filipinos? It simply tells them where they’ve been and where they could go. It tells a story that everyone can appreciate and relate to, which is why it’s a big part of every Filipino culture.

During the 1980s, Rossana was the lead dancer of the Manisan Cultural Dance Troupe. I got to know about gong music, which can be divided into two types: the flat gong, commonly known as gangsà, played by groups in the Cordillera region, and the bossed gongs played among the Islamic and animist groups in the southern Philippines.

The kulintang ensemble is the most advanced form of ensemble music with origins in the pre-colonial epoch of Philippine history and is a living tradition in the southern parts of the country.

Very quickly, I discovered another popular medium for light classical music: the rondalla. Its repertoire consists mainly of native folk tunes, ballroom music, and arrangements of classical pieces such as opera overtures.

Bayani de Leon and Jerry Dadap have written more serious music for the rondalla. Rondalla is a traditional string orchestra comprising two-string, mandolin-type instruments such as the banduria and laud, a guitar, a double bass, and often a drum for percussion.

The rondalla has its origins in the Iberian rondalla tradition and is used to accompany several Hispanic-influenced song forms and dances.

Tinikling and Cariñosa inspired me more and more. The Tinikling is a dance from Leyte involving two performers hitting bamboo poles, using them to beat, tap, and slide on the ground, in coordination with one or more dancers who step over and in between poles. It is one of the more iconic Philippine dances and is similar to other Southeast Asian bamboo dances.

The Cariñosa, meaning “loving” or “affectionate one,” is the national dance and part of the María Clara suite of Philippine folk dances. It is notable for using a fan and handkerchief to amplify romantic gestures expressed by the couple performing the traditional courtship dance.

The dance is similar to the Mexican Jarabe Tapatío and is related to the Kuracha, Amenudo, and Kuradang dances in the Visayas and Mindanao regions.

In my early years as an expat in the Philippines, I seemed to have forgotten my classical music from Europe, focusing more on Himig ng Pilipinas—the musical performance arts in the Philippines or by Filipinos composed in various genres and styles. The compositions are often a mixture of different Asian, Spanish, Latin American, American, and indigenous influences.

Notable folk song composers include the National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro, who composed the famous “Sa Ugoy ng Duyan” that recalls the loving touch of a mother to her child. Another composer, the National Artist for Music Antonino Buenaventura, is notable for notating folk songs and dances. Buenaventura composed the music for “Pandanggo sa Ilaw.”

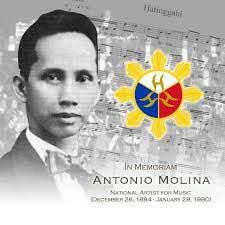

The leading figures of the first generation of Philippine composers were Nicanor Abelardo, Francisco Santiago, Antonio Molina, and Juan Hernandez.

But one composer and his works fascinated me the most: Francisco Buencamino. He belonged to a family of musicians. Born in San Miguel de Mayumo, Bulacan, on November 5, 1883, he founded the Academy of Music of Buencamino in 1930. His musical styles included kundimans and zarzuela.

Francisco first learned music from his father. By age 12, he could play the organ. At 14, he studied at the Liceo de Manila, taking courses in composition and harmony under Marcelo Adonay, and piano-forte courses under a Spanish music teacher. He did not finish his education, becoming interested in the zarzuela. Some zarzuelas he wrote include “Marcela” (1904), “Si Tio Celo” (1904), and “Yayang” (1905). In 1908, the popularity of the zarzuela waned due to American repression and the entry of silent movies. Francisco then turned to composing kundimans.

For a time, Francisco Buencamino frequently acted on stage. He collaborated on plays written and produced by Aurelio Tolentino. One of his earliest compositions is “En el bello Oriente” (1909), using Jose Rizal’s lyrics. “Ang Una Kong Pag-ibig,” a popular kundiman, was inspired by his wife. In 1938, he composed an epic poem that won a prize from Far Eastern University during an annual carnival. His “Mayon Concerto” is considered his magnum opus. Begun in 1943 and finished in 1948, “Mayon Concerto” had its full rendition in February 1950 at the graduation recital of Rosario Buencamino at the Holy Ghost College. “Ang Larawan” (1943), another acclaimed work, is based on a Balitaw tune. The orchestral piece “Pizzicato Caprice” (1948) is a version of this composition. Many of his other compositions were lost during the Japanese Occupation, when he evacuated his family to Novaliches, Rizal.

I would say that “Pizzicato Caprice” is my favorite. I was fortunate to experience it during an exceptional performance with the Manila Symphony Orchestra.

Outstanding groups include not only the Manila Symphony Orchestra but also the Filipino Youth Symphony Orchestra, the U.P. Symphony Orchestra, the Manila Concert Orchestra, the Quezon City Philharmonic Orchestra, the Artists’ Guild of the Philippines, the Philippine Choral Society, the U.P. Madrigal Singers, and the U.P. Concert Chorus, among others.

These are extraordinary treasures of Filipino culture, which are too often unheard and unexperienced these days.

The music of my life started at age six with my first steps on the piano playing Beethoven’s “Für Elise.” I remember my very first LP on my birthday gifts table: Serge Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf.”

In an autobiographical sketch, the Russian composer described the three chief qualities of his complex work as: a classical or rather classicist tendency, an emotional vein, and a grotesque element, which he detected as “fun, laughter, satire.” “A symphonic tale for children” awakened my dream of classical music.

Despite this drastic sound-painting portrayal, the general effect produced is not that of a musical jest, but—thanks to Prokofiev’s artistry and skill—one of singular poetry.

There are few musicians with such eloquence and improvisational skills as Sergei Prokofiev, the Russian composer of many talents, including the piano and keyboards. Born to a well-off family in 1891, Prokofiev’s first exposure to music was through his mother, who spent two months a year learning the piano and played a few sonnets every evening. Prokofiev began learning the piano instantly and became so proficient that he composed his first piano piece under his mother’s watchful supervision. Before the age of 10, he had also shown interest in opera music and started work on his first opera, “The Giant.”

In his early years, Prokofiev’s parents were adamant about providing him with theory lessons to clarify his conceptual frameworks for piano and composition. However, they soon had second thoughts about their young son pursuing a music career at such a delicate age, enrolling him in the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. There, he learned piano and other instruments under renowned composers such as Alexander Winkler, Nikolai Tcherepnin, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Before his father’s death in 1910, he had started performing in local clubs and venues like the St. Petersburg Evenings of Contemporary Music, performing some of his early Piano Sonatas such as “Four Etudes for Piano, Op 2” (1909). Throughout the early 1910s, Prokofiev experimented with various genres, including ballet music. While he succeeded in many compositions, he struggled with ballet music, with “Chout” undergoing significant modifications in the 1920s.

Facing limited opportunities in the 1930s due to the Great Depression, Prokofiev moved to Russia in 1936. This period marked some of his most impressive works. Despite the hostile reality of the time, themes in works like his orchestral piece “Russian Overture” (1936) and “War Sonatas” embraced war-related topics. However, Prokofiev retained his incredible ingenuity with compositions such as “Peter and the Wolf,” “Alexander Nevsky,” and “Romeo and Juliet,” all of which were well-received internationally. These compositions remain widely performed today.

The war and post-war years saw impressive compositions such as “War and Peace,” “The Ballet Cinderella,” and various violin sonatas, showcasing Prokofiev’s remarkable contributions to classical music despite facing numerous challenges.

Because of Prokofiev, my world of classical music first opened up to Russia. Not to Germany or Austria, not to Beethoven or Liszt, Mozart, or others. Suddenly, I fell in love with Tchaikovsky. His first piano concerto in B-minor left me speechless and in tears at every stage play, a blessing throughout my life.

The very first bars of this piano concerto are so distinctive they remain in the listener’s memory forever. Tchaikovsky’s “Piano Concerto No. 1” is recognizable and catchy. Charismatic piano virtuoso Martha Argerich lent an elegant lightness to this impressive piece, performing with the Verbier Festival Orchestra at the Verbier Festival in 2014, conducted by Charles Dutoit. (To be continued)