By Institute of Contemporary Economics

“…energy systems across countries are unique to local circumstances, the economic structure, socio‑economic priorities, and countries will adopt multiple pathways to pursue an effective energy transition.” – Roberto Bocca, Head of Shaping the Future of Energy and Materials, Member of the Executive Committee, World Economic Forum The Importance of a Planned Energy Transition

As we continue to aim for the decarbonization of our power sector, it is of high importance that we understand the implications and challenges of doing so to avoid or, or at least, mitigate prospective negative impacts on our people. As it is, the dream of 100% renewable energy (RE) remains a subject of fervent debate. While great strides have been made in terms of research, technology and actual implementation in this area, the question remains – is 100% renewable energy even plausible?

Assuming for the sake of argument that it is, we ask what it will take to get there. It is also important to ponder and lay out the potential impacts on our economy and our people. It is simply not a matter of putting up more solar plants and wind farms to replace our current fossil-fuel dependent power plants.

We already know that these variable sources of energy put into risk the stability of our electricity supply if the transition is not done in an orderly manner. Even while significant progress has been made in storage batteries, we are far from the scale that is necessary to provide the stability to our energy supply.

Jumping off from the quote above from Mr. Bocca, it is critical that we study our unique local circumstances as we transition towards a more climate-friendly energy sector. We need to be able to map out the implications of this transition and its various impacts beyond our energy use. From here, we can then choose the pathway(s) that we will adopt towards an effective energy transition. Our view is that a thoughtfully planned transition is not only preferable but necessary as against a dogmatic approach which may cause more harm than good.

What is a 100% renewable-powered grid?

In anything that we aim for, it is important, at the start to define exactly what it is that we are aiming for. Neglecting to do so would potentially lead to a meandering, inefficient and possibly harmful journey.

So, what is a 100% renewable-energy grid? In a paper (1) published in the journal Joule, Paul Denholm (and his co-authors), the principal analyst of the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, break down two key aspects of a definition. These aspects are the technology type and the system boundary.

The technology type is broken down into two specific technology types – variable and non (or less) variable renewable energy. Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) relies on short-term weather conditions to produce energy such as wind and solar. Non-VRE technologies include hydro, biomass, geothermal, and concentrated solar power (using thermal batteries).

The second aspect of the definition is system boundary. This aspect defines a 100% RE-grid as operating with 100% RE supply at all times. This contrasts this with the achievement of 100% RE via the use of RE credits and other financial mechanisms.

These two aspects essentially define 100% RE as (1) having energy supply coming from the aforementioned technology sources and, (2) operating with 100% RE supply at all times. So how do we get there (if we can get there at all)?

Considerations for a Rational Energy Transition

The World Economic Forum (WEF) lays out 5 imperatives for the energy transition (2). These include:

(1) Regulations and political commitment

(2) Capital and investment

(3) Innovation and infrastructure

(4) Economic structure

(5) Consumer engagement

We do not intend to go through all of these considerations in this paper but would like to highlight certain components that we feel have significant relevance to our situation.

The Paris Agreement

The drive for a transition towards renewable energy should not be viewed in isolation. It is a means to an end which is ultimately defined in the Paris Agreement (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). To quote, “this Agreement…aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, including by holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.” While not explicitly mentioned in the Agreement, the reduction in the use of fossil fuels as a main driver of climate change becomes an obvious and pressing target. Without denigrating its importance, it is a means to an end.

Given this context, it is also useful to point out that any climate change mitigation initiative needs to be mindful of “sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.” A mindless energy transition could have the impact of negating the need for balance that we are reminded of in the Agreement itself.

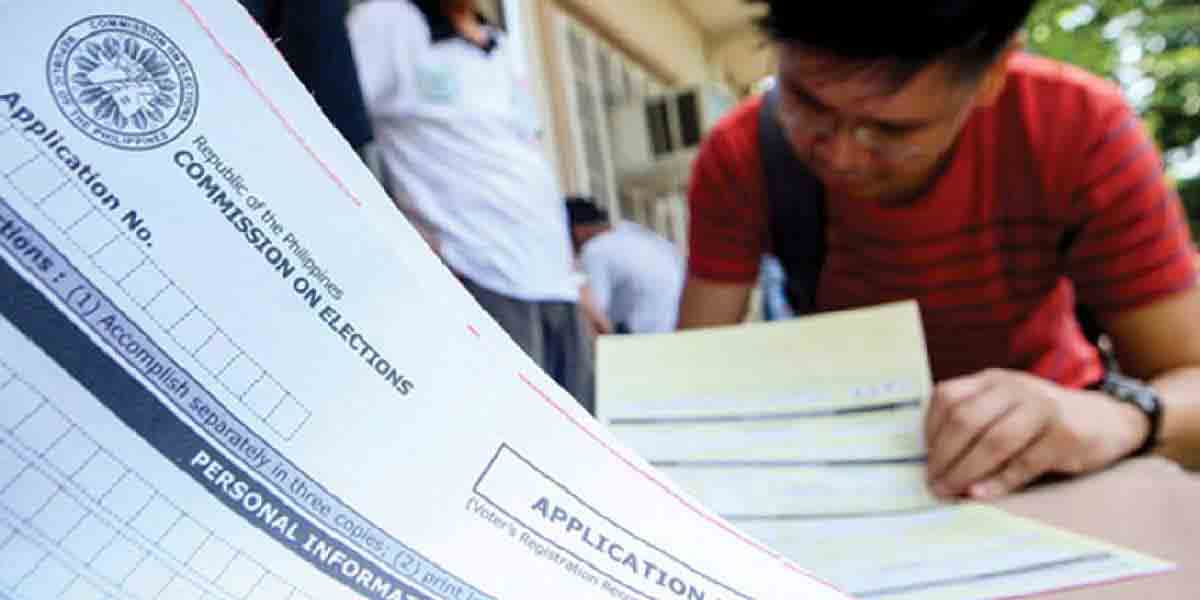

Having said that, we do need to accelerate the process of actually implementing the measures aimed at fulfilling our commitments. As a background, the Philippines was one of the original signatories of the Paris Agreement in 2016. We submitted our Nationally Determined Contribution in 2021 which essentially promised to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 70% by 2030. In July of this year, the Philippines released its Implementation Plan (3) and also increased the promise to reduce GHG emissions to 75%.

The recommendations of the WEF regarding Regulations and Political Commitment cite the importance of the following:

(1) Net‑zero emissions commitments need consistent definition, tangible roadmaps and milestones.

(2) A sector‑specific approach, gradual implementation and distributional considerations are critical for success where carbon pricing mechanisms are established.

(3) Incentives and regulations can increase the coverage of corporate commitments to climate action.

Unfortunately, the Philippines does not have a net-zero commitment. Moreover, of the 75% promise in GHG, only 2.71% unconditional while the balance is conditional primarily on international financial support.

Paradoxically, while there is the need for some sense of urgency, this should not be focused solely on our energy transition but also on the other components of the Philippines’ NDC Implementation Plan. There are items contained in the plan that are in more critical need of attention and which will have a greater impact on progressing towards our GHG emissions reduction promises (note: the Institute will have a separate paper on the NDC IP).

Look at Demand Side

For all the hullaballoo of climate change mitigation and adaptation, there has been a disappointing neglect on actions to reduce consumption. In a sense, the supply side of energy transition has been a center of focus due to its being an easier area to understand. This should not, however, be an excuse to ignore the contribution that a current or more, appropriately, a future relative reduction in energy consumption will have on GHG emissions. We venture to opine that this has been shunted aside given a difficulty in appreciating the measures which need to be taken.

This can be boiled down to two words – energy intensity. In simple technical terms it measures how much energy we use to produce a certain level of economic output. Changing this to make our economy more energy efficient is not a simple exercise but it has significant implications on our impact on climate change. Its impact will be immense. One analogy would be to use behavioral change to reduce the incidence of chronic illnesses which bedevils many of us.

The first step will have to be establishing a baseline as to how we currently use energy. All of our industries use energy to varying degrees. Solutions will involve emphasizing one industry over another as well as changing how we do things in certain industries.

As an example, “numerous studies have quantified GHG emissions within agriculture and food systems, covering aspects like land use, the production and utilization of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, enteric fermentation from livestock production, and the entire spectrum of food production, transportation, and consumption” (4). Further, a study conducted on EU farms concluded that “the use of fertilizer is the largest energy consuming activity in EU open-field agriculture, accounting for around 50% of all energy inputs. On-farm diesel use accounts for 30%, while other uses are mainly dedicated to irrigation, storage and drying, pesticides and seeds, each accounting for 5% of total energy inputs (5)”. While our experience may be different, given that agriculture is the dominant industry in our economy isn’t it high time that we look at how we can find ways to make it more energy efficient?

Summary

The transition from a predominantly fossil-fuel based energy industry to renewable energy is essential to addressing climate change and its impact. It is important that we manage this transition in a thoughtful and meaningful manner to avoid and mitigate any negative effects on people during the transition. A comprehensive roadmap at the local/LGU level should be a requirement to ensure an effective transition.

We should begin to seriously address the way we use energy down to the industry level. Our impact on climate change and its related implications will be muted if we continue to use energy the way we have always used it. The full benefit of resolving supply side issues (i.e. renewable energy transition) will not be fully realized unless we seriously look at demand-side factors.

It is accepted fact that human beings have been the primary cause of environmental degradation. We would argue that the bigger culprit has not been where we get our energy from, it is from how we use it.

End Notes

(1) Denholm, P., Arent, D. J., Baldwin, S. F., Bilello, D. E., Brinkman, G. L., Cochran, J. M., Cole, W. J., Frew, B., Gevorgian, V., Heeter, J., Hodge, B. S., Kroposki, B., Mai, T., O’Malley, M. J., Palmintier, B., Steinberg, D., & Zhang, Y. (2021). The challenges of achieving a 100% renewable electricity system in the United States. Joule, 5(6), 1331–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2021.03.028

(2) World Economic Forum. (2020). Fostering Effective Energy Transition.

(3) Climate Change Commission & Department of Environment and Natural Resources. (2023). IMPLEMENTATION PLAN FOR THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES NATIONALLY DETERMINED CONTRIBUTION (NDC) 2020–2030

(4) Qin, J., Duan, W., Zou, S., Chen, Y., Huang, W., & Rosa, L. (2024). Global energy use and carbon emissions from irrigated agriculture. Nature Communications, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47383-5

(5) Paris, B., Vandorou, F., Balafoutis, A. T., Vaiopoulos, K., Kyriakarakos, G., Manolakos, D., & Papadakis, G. (2022). Energy use in open-field agriculture in the EU: A critical review recommending energy efficiency measures and renewable energy sources adoption. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 158, 112098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112098

The Institute of Contemporary Economics is a multi-disciplinary think tank which aims to be a credible thought leader in the policy-making space. It seeks to promote a vibrant and sustainable economic environment particularly in Western Visayas.