By Yann Perreau

Prehistory is a modern idea. The word was “coined” only in the 1830s. Before the 19th century, we didn’t know much about dinosaurs or cavemen, and fossils remained a scientific curiosity. When French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon published his notorious Histoire naturelle (1749–1788), suggesting that nature had a history and proposing the first reproduction theory, the faculty of theology at the Sorbonne University in France condemned it and threatened him with repercussions. He eventually had to publish a retraction.

Similarly, when Charles Darwin (1809–1882) published his On the Origin of Species (1859), his compatriots in the United Kingdom and Europe still believed that God made man “in his own image,” as stated in the Bible (Genesis 1:27). Anyone claiming that all animals came from the same origin, and apes were somehow our distant cousins, was considered a fool or a heretic.

Then the first caves were excavated revealing extensive and intricate artwork on their walls. In 1879, archeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola explored a new cave in Altamira, northern Spain, and brought his young daughter, Maria, with him. She spotted vivid depictions of bison and masterfully painted scenes on the cave’s ceiling. These cave paintings were initially dismissed as forgeries, as scholars of the time, with the positivist mindset, could not imagine that people from the Paleolithic were sophisticated enough to produce such complex artworks. By the early 20th century, however, as archaeologists uncovered more ancient skeletons, bones, fossils, and early human art in caves and other sites, their discoveries started to raise curiosity beyond the scientific community. Writers, intellectuals, and the public were captivated by these glimpses into our distant past.

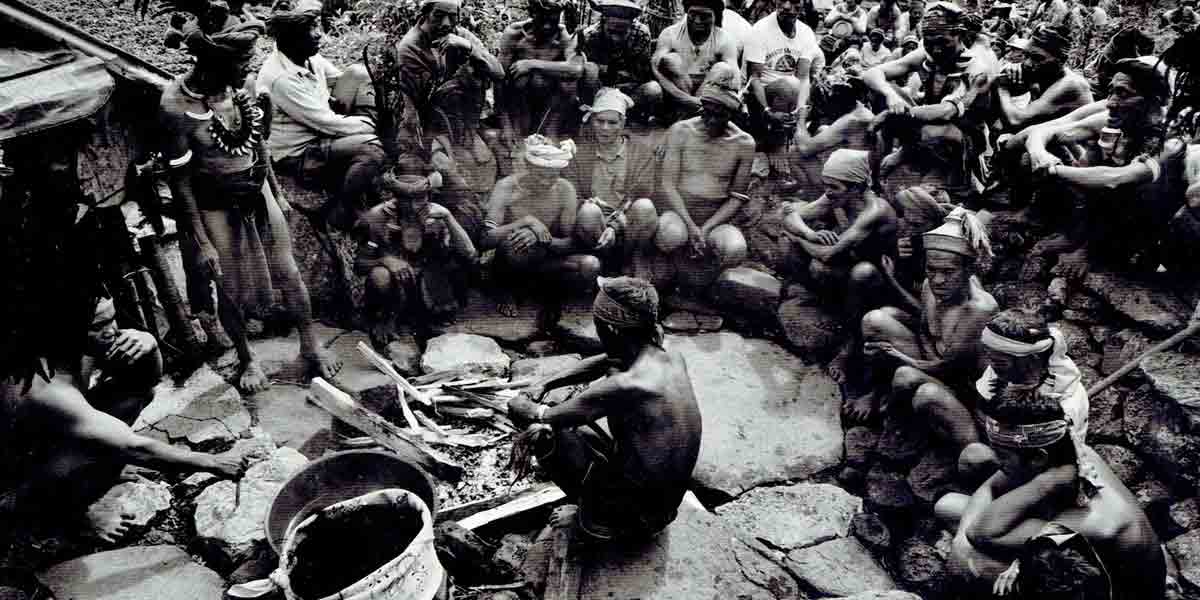

Artists were intrigued, sometimes amazed by the mind-blowing quality of parietal art, indecipherable, complex abstract shapes and objects, and what was perceived as scenes depicting animals and humans in rituals or sacrifices. The drawings, paintings, and etchings that endlessly decorated the walls, ceilings, and floors of caves in subtle colors were often mesmerizing. Picasso was particularly inspired by various prehistoric elements, as the 2023 exhibition No Past in Art: How Prehistory Inspired Picasso’s Work at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris showed. Gauguin, Cézanne, and later the symbolists and primitivists, also dedicated various paintings and sculptures to what they perceived as representations of our origins, rituals, and myths.

Prehistory has never stopped inspiring artists since then, captivating the most important modern art figures like Jean Arp, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, Paul Klee, Joan Miró; Joseph Beuys, Louise Bourgeois, Jean Dubuffet, Marguerite Duras, Barbara Hepworth, Yves Klein, and Robert Smithson. It continues to be an inspiration among our contemporaries, including Dove Allouche, Miquel Barceló, Tacita Dean, Marguerite Humeau, Pierre Huyghe, and Giuseppe Penone, to name just a few, whose works were showcased during the 2019 exhibition, Préhistoire, une énigme moderne (Prehistory, a Modern Enigma).

This landmark exhibition, which took place at the Pompidou Center in Paris, inspired me and initiated my interest in prehistory. It is not the first museum show dedicated to the topic: fossils, artifacts, and artworks discovered in caves, as well as tools, ornaments, and sculptures made from natural rocks, have been exhibited in major art institutions since the end of the 19th century.

Most of these exhibitions have already created fruitful dialogues between the past and present and parietal art and its representation by contemporary artists. When it opened its Gallery of Comparative Anatomy and Paleontology in 1898, the National Museum of Natural History in Paris commissioned the sculptor Emmanuel Frémiet and the painter Fernand Cormon to create a vast decorative program. Prehistoric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, New York, 1937) showed monumental surveys of cave paintings with a selection of contemporary works by Miró, Klee, and Ernst, among others, in echo. “That an institution devoted to the most recent in the art should concern itself with the most ancient may seem something of a paradox,” MoMA’s founding director Alfred H. Barr Jr. wrote in his preface to the exhibition catalogue. “Yet, for Barr, this past had already influenced modern art, and could potentially offer museum visitors a prehistoric pedigree for it,” states the MoMA website. Another major exhibition, 40,000 Years of Modern Art, organized by Herbert Read and Roland Penrose at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1948, mixed prehistory and non-Western art with surrealist, expressionist, and abstract works.

But there is a major problem, particularly, concerning the so-called “primitive art,”—a highly contested term now. The clichés and stereotypes that this notion implies were also abundant in the early “scientific” literature dedicated to our ancestors. The first paleontologists were poisoned by plain racist prejudices, explains paleo artist and author Mark P. Witton in his 2020 blog. George Cuvier (1769–1832), the father of vertebrate paleontology whose famous taxonomy incorporated both fossils and living species, “viewed whites as the pinnacle of creation, but Blacks as ugly, barbaric persons of monkey-like appearance,” writes Witton. “His work on dividing humans into ‘scientifically validated’ races was instrumental in later attempts at biological justifications of racism.”

In the United States, the influential president of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857–1935) was a supporter of Hitler. He exploited his research to promote racist and eugenicist ideas, points out Witton. Osborn commissioned one of the earliest depictions of prehistoric life, Charles Knight’s mural “Neanderthal Flintworkers” (1924), hung in AMNH’s Hall of the Age of Man. Many of Osborn’s contemporaries, including Margaret Mead, were troubled by the racist character of the imagery. The faces and looks of the Neanderthal men and women depicted in this iconic—though controversial and scientifically incorrect work—were inspired by features of non-white peoples, instead of being deduced from their bones.

A Eurocentric mindset has continued to characterize the collective representation of prehistory until recently, sometimes reducing it to a more subtle form of “primitive art.” In 1984, MoMA dedicated a survey exhibition to “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art. MoMA bragged about being the first institution to “juxtapose modern and tribal objects in the light of informed art history.” But the exhibition omitted dates of the Indigenous works and explanations of their functions, as art historian Thomas McEvilly remarked in his Artforum review of the show. He criticized Primitivism in 20th Century Art as expressing “Western egotism still as unbridled as in the centuries of colonialism and souvenirism.” Since then, the museum has made its mea culpa, addressing the controversy on its website.

The Pompidou exhibition’s three curators, Cécile Debray, Rémi Labrusse, and Maria Stavrinaki, write on the museum website that Primitivism in the 20th Century Art did not include prehistory “which, in fact, is fundamentally different from it. For the modern Western world, the ‘primitive’ is generally rooted in specific cultures, usually described as exotic; the question of temporality is secondary to its geographical and cultural otherness. Prehistory, on the other hand, is seen above all as an indefinitely stretched time span, and thus largely indecipherable (whether in terms of nature or the first human cultures).” Labrusse dedicated a book to this paradoxical situation. “Prehistory is precisely what is pre, meaning out of history,” he told me in an interview in October 2024. It “radically overturned our dream of mastering linear time, as 19th-century historicism chose to formulate it.” Here lies the paradox that attracts so many artists to prehistory, according to Labrusse: “Because it is largely indecipherable (whether in terms of nature or the first human cultures), it remains fascinating.”

From Prehistory, a Modern Enigma, I remember the scenography. Tall walls, obscure corridors, grandiose frescos, and a prehistoric cave reconstituted at the center of it. In this spectacular setting, amid fossils, Cro-Magnon skulls, tools, and Paleolithic carvings, there were more than 300 works of art by modern and contemporary artists. Plus elements of popular culture: surveys of archaeological excavations, advertisements, and extracts from books (The Quest for Fire, a hugely popular Belgian 1911 fantasy novel) and cult films such as The Lost World (1925), King Kong (1933), or 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). This undertone in the exhibitions shows what the curators of the Pompidou exhibition describe as the “invention of the concept of prehistory.” How artists and society have succumbed to the appeal of origins in the modern era, “yielding to a fantasized vision of what came before history.”

The exhibition opened with Odilon Redon and Paul Cézanne, at the turn of the 20th century. Cézanne was an amateur student of geology and paleontology. He visited prehistoric caves and painted the rocks on the Mediterranean coast with his close friend Antoine-Fortuné Marion (1846–1900), who later became a noted geologist and paleontologist. The show also exposed the Venus of Lespugue, the famous prehistoric ivory statuette, dated around 23,000 years ago, which inspired Picasso and Giacometti (both owned plaster casts of it). She stands there, in an exhibition room at the Musée de l’Homme, surrounded by bronzes from Matisse, Miró, and other modern artists who were equally fascinated by her and other statues from that time.

“Préhistoire, une énigme moderne” brilliantly demonstrated how prehistory inspired modernity, an artistic movement that was, paradoxically, about the future. Photos of the 1889 Paris World’s Fair show how the Eiffel Tower and various cutting-edge technologies were exhibited alongside Neanderthal skeletons. A Max Ernst painting of “petrified forests, glacialized landscapes, and sedimented earth,” created after World War I, raised questions about whether these were depictions “from after humanity, or before it?” as modernism developed toward “a prehistoric vision of time before humankind,” according to a 2019 New York Times article.

This feeling got stronger with the tragedies of World War II when many intellectuals and artists turned their back on the notion of progress, digging in reverse into the beginning of life, extinct species, the first hominids, the lost cultures of the Paleolithic era, and the Neolithic revolution to grapple with the possibility of extinction, of earth without humankind. “Nourished by archaeological discoveries, but far from simply reflecting on them,… prehistory…[functioning] as a powerful machine for stirring up time,” write the curators. “This time machine constantly shapes the mental boundaries of modernity and provides concrete models for all sorts of experiments.”

The exhibition also explores the mysteries of shaped rocks and tools, an intimate relationship to animals, ecological issues, and apocalyptic wonder in chronological and thematic parcourse. These themes are part of the collective representation, the idea of what prehistory is and how the inspired artists, whose works were exhibited, felt from Louise Bourgeois, Joseph Beuys, Lucio Fontana, Max Penck, Robert Morris, Robert Smithson in the 1980s, the Chapman brothers, Pierre Huyghe, Tacita Dean, Marguerite Humeau, Dove Allouche, Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, Jean-Pascal Flavien, and Bertrand Lavier in the last few years. “Prehistory is not an object given to artists to interpret; it is created by them” states Labrusse.

“I think artists are either Paleolithic or Neolithic. I am decidedly the latter said minimalist artist Carl Andre, according to the previously mentioned NYT article. His Stone Field Sculpture in Hartford, Connecticut, could have belonged to the Neolithic times. Painters and sculptors sometimes like to experiment with the artistic canons and the tradition of “getting back to our roots,” to the “early man,” as a 2024 exhibition at the Hole Gallery shows. “Based around an out-of-print anthology devoted to prehistoric collections unearthed by archaeological expeditions in Algeria, French artist Camille Henrot’s… [Prehistoric Collections] treats this ethnographic material as motifs of a contemporary grotesque,” states the Perimeter Books’s website.

Meanwhile, Mark Dion’s immersive, uncanny installation at La Brea Tar Pits and Museum in September 2024, Excavations, displayed new work alongside “early museum murals, dioramas, and maquettes of Ice Age mammals in a playful… presentation,” the museum website states.

Labrusse recalls feeling “powerless” when he started applying his scientific skills and methods to prehistoric art (he is a professor of art history at École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales). “History requires context, facts, and elements to narrate it. These things are almost nonexistent when one looks back so far behind in time,” he explains. Many social scientists who study prehistoric history testify to a similar challenge. There is little evidence from prehistoric times and huge gaps of time for which the evidence is completely missing. “Prehistorians have the scientific honesty to recognize an irreducible ignorance, an impossibility of bringing out meaning,” notes Labrusse. “It is impossible to give a social, political, or aesthetic meaning to these societies.” During a podcast interview in 2019, he explained feeling first “like falling into a hole, caught up in an abyss of darkness. Then, as in Alice in Wonderland, you start to see through the looking glass.”

For him, the turning point came while exploring a prehistoric cave, a “very intimate, life-changing experience,” he says during the interview with me. Discovering parietal scenes in the cave of Roucadour, Labrusse felt “as if they were contemporary. There is no context there, and things seem to float outside of any attributable meaning, so their appropriation is immediate, easy.” I learned this way to “let go of the burden of history,” which “dissolved like a soap bubble.” He recalls being tempted to touch these walls, reproducing these same gestures that the first men did back then. “Science now tells us that Homos sapiens has been the same for 100,000 years, even 300,000 years. Individuals have the same capacities, even possibly the same feelings as us today.”

The limits of science, when confronted with prehistory, are also an opportunity that artists have often seized to contribute to the field in their own way. It gives them a chance to tell this story differently. Aware of this, contemporary prehistorians sometimes invite painters or sculptors to work with them to create interdisciplinary meaning, an epistemology articulating a subjective point of view (art) with an objective approach (science).

The French government invited artists Ernest Pignon-Ernest, Giuseppe Penone, and Miquel Barceló, among others, to bring “Other Perspectives” to the Chauvet-Pont d’Arc cave. To understand how a howl decorating the cave had been originally drawn, Barceló recreated first the same wet surface that was used by his predecessor as a canvas 35,5000 years ago. He then drew a few lines like a graffiti artist in less than 10 seconds. His audacious and instinctive gesture was brilliant: the resulting drawing looked remarkably similar to the original one. “Only an artist can do this with his subjective impulsivity,” comments Labrusse. “A historian would not have dared to do it, keeping a rigorous mindset in his attempt to reproduce the drawing and, ultimately, failing to do so.”

In another style, the notorious Adrie and Alfons Kennis, twin brothers who are “paleo artists,” are creating lifelike figures of early man that are touring museums and galleries around the world. Their hominids are fascinating and are another example of what art and science can do when working hand in hand.

Yann Perreau is a writer, educator, contemporary art curator, and writing fellow for the Human Bridges project of the Independent Media Institute. He has published several books on art, climate, anonymity, and more. His articles have appeared in many publications, including Libération, Art Press, and East of Borneo. He has served as a cultural attaché for both the French Embassy in London and the French Consulate in Los Angeles. He holds an MPhil in art history from Paris’s EHESS. This article was produced by Human Bridges.