By Rjay Zuriaga Castor

Iloilo City’s information ecosystem is being flooded with political content — some of it openly sponsored, some more covert. What appears on the surface to be standard press releases from vaguely named civic groups is, upon closer inspection, a coordinated campaign aimed at shaping public perception of candidates in the local elections.

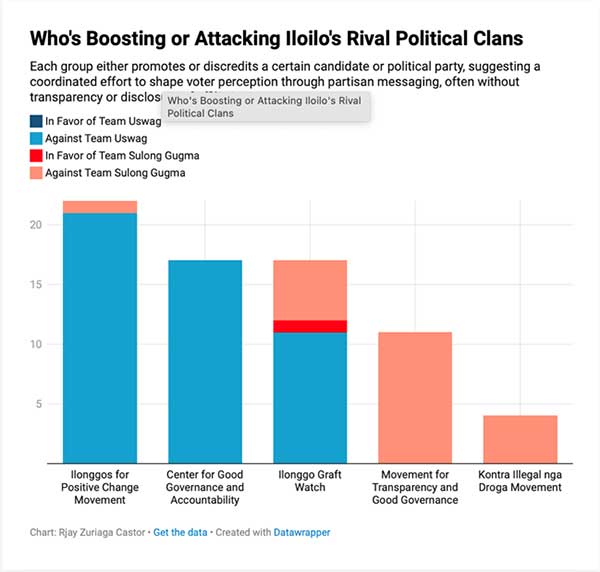

A months-long investigation by Daily Guardian found that at least seven anonymous or loosely named groups have released a total of 71 paid press statements that have overwhelmingly targeted — or favored — Team Uswag of Iloilo City Mayor Jerry Treñas and Team Sulong Gugma of lone district Rep. Julienne “JamJam” Baronda.

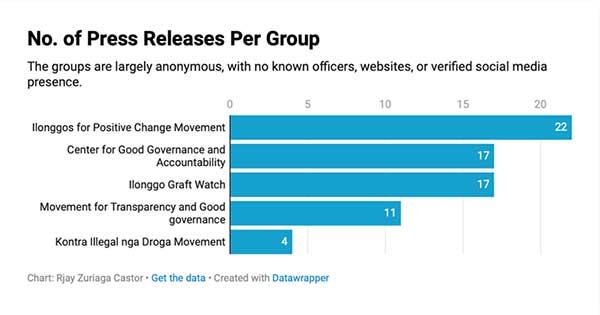

These groups have identified themselves as Ilonggo Graft Watch, Ilonggos for Positive Change Movement, Center for Good Governance and Accountability, Movement for Transparency and Good Governance, and Kontra Illegal nga DrogaMovement.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/in1cs/

A common thread runs through them: they are all largely anonymous, with no public websites, social media presence or identified officers.

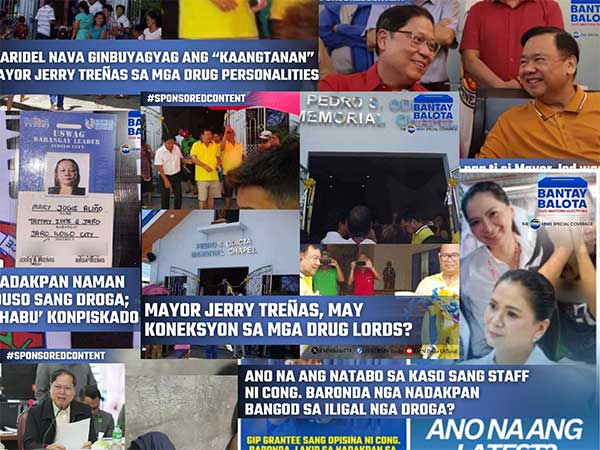

Statements from each group are labeled as #SponsoredContent, #SponsoredPost or #PaidPost when carried by media outlets, signaling that the material is paid advertising.

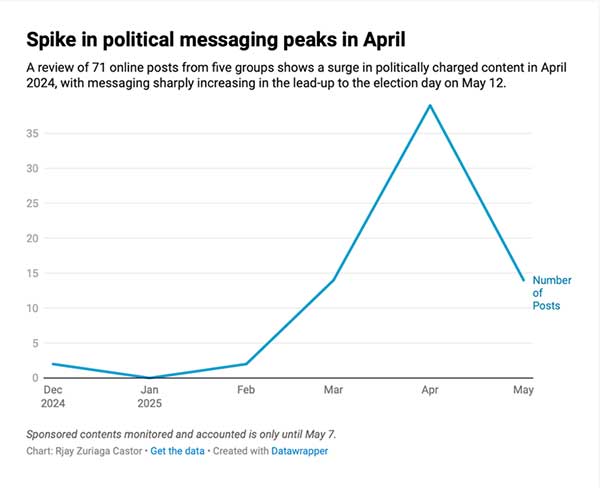

While political advertising is not new, the volume, anonymity and timing of these content blasts suggest an orchestrated effort to shape voter perception ahead of the May 12 polls.

A coordinated timeline of attacks

The earliest wave came from the Kontra Illegal nga Droga Movement in December 2024, which resurfaced the 2014 Commission on Audit disallowance against former Mayor Jed Patrick Mabilog and flagged unliquidated intelligence funds from his administration.

Then came a lull.

Though Mabilog isn’t seeking office, he remains politically active as campaign manager for Baronda’s Team Sulong Gugma.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/YZbbR/

By mid-March—just as the official local campaign period began—the stream resumed with renewed force.

The content turned aggressive, attacking candidates’ alleged ties to drugs, nepotism, poor legislative records or misuse of public funds.

In late April to early May, just weeks before election day, posts shifted toward personal attacks—alleging extramarital affairs, unexplained wealth and labeling opponents as “desperate” or “unfit.”

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/1sgGf/

Daily Guardian’s analysis of the paid posts suggests that the content is part of a coordinated campaign aimed at damaging or boosting a specific candidate’s or party’s credibility in the final stretch before voting.

The group Ilonggos for Positive Change Movement zeroed in on Vice Mayor Jeffrey Ganzon, contrasting his legislative record unfavorably with that of his rival, former city councilor Love-Love Baronda.

They targeted Ganzon’s legislative track record over his 18-year tenure in the Iloilo City Council, comparing it to Baronda’s 91 authored ordinances and 960 resolutions in just nine years as a councilor.

To further discredit Ganzon’s reelection bid, the group quoted disbarred lawyer and former councilor Plaridel Nava, who called the incumbent vice mayor “weak, incompetent and unworthy” to hold office.

The group is also reviving the 2019 Ombudsman complaint against Ganzon, alleging he appointed several family members to city government positions who received salaries without performing official duties—effectively accusing him of employing “ghost employees.”

The group positions Baronda as a more productive, capable and collaborative alternative, highlighting her legislative efficiency and alignment with the executive branch.

The same messaging is echoed by Iloilo Graft Watch, where Ganzon is also a primary target. The group again quoted Nava’s statements dismissing Ganzon’s capability.

One press release from Graft Watch, dated March 14, cited Baronda’s legislative accomplishments—suggesting the group’s alignment with the vice mayoral candidate.

Infrastructure delays, anomalies

Though not a candidate in the midterm polls, Treñas is a frequent target of the Center for Good Governance and Accountability, which blames him for a long list of stalled infrastructure projects funded by a billion-peso loan.

Projects such as the Iloilo City Hospital, multi-level parking buildings and public markets in Arevalo, La Paz and Jaro are cited as examples of the 190 city infrastructure projects delayed under the Treñas administration.

The group also raises concerns about alleged violations of building code regulations, claiming that several projects during Treñas’ term as congressman lacked proper permits.

They argue these delays betray public trust, particularly in the case of the hospital project, which was promoted as offering free hospitalization for Ilonggos.

Meanwhile, Ilonggo Graft Watch paints Baronda as emblematic of political hypocrisy and corruption.

The group accuses her of shirking responsibilities and accumulating unexplained wealth, particularly in connection with incomplete public projects.

Two key cases are frequently cited: the PHP19.2-million multipurpose hall in Barangay Concepcion and the PHP24.6-million evacuation center in Barangay Katilingban, Molo—both of which remain unfinished despite funding.

Drug links

The messaging propagated by the Kontra Illegal nga Droga Movement links current drug-related controversies to incumbent politicians such as Rep. Baronda, while also reviving old corruption and audit issues involving former Mayor Mabilog.

Iloilo Graft Watch goes beyond corruption allegations, claiming that Mayor Jerry Treñas has maintained ties with known drug figures, particularly the late Melvin “Boyet” Odicta and his family.

This stands in direct contradiction to the mayor’s public anti-drug stance and his recent condemnation of Mabilog, whom he labeled a “drug protector”—a sharp reversal from his previous defenses of Mabilog in 2024.

The accusations are amplified by public statements and online posts from political figures like Plaridel Nava and businessman Rommel Ynion, who are frequently cited by these groups.

They further attempt to erode the credibility of Team Uswag by pointing to the recent arrest of a party leader on drug-related charges, framing it as evidence that Treñas’ political organization is either complicit in or ineffective against the drug trade in Iloilo.

The Movement for Transparency and Good Governance has also singled out Baronda’s camp. One press release references the arrest of two barangay leaders allegedly affiliated with Sulong Gugma during a buy-bust operation.

The incident is framed as a continuation of the drug-related controversies that plagued the Mabilog administration, reinforcing claims that the alliance is tainted by criminal ties.

Unexplained wealth

Iloilo Graft Watch also targets Baronda’s alleged unexplained wealth—pointing to her ownership of luxury cars, upscale condominiums and branded accessories.

Earlier this April, Nava filed a formal complaint before the Ombudsman, citing these concerns and referencing much of the material previously circulated by Iloilo Graft Watch.

The group, through its press releases, openly calls on voters to reject Baronda in the May elections, portraying her as a politician who has repeatedly broken promises, misused public funds and failed to deliver basic infrastructure.

The Movement for Transparency and Good Governance has also joined the fray, casting doubt on Love-Love Baronda’s campaign platform and character.

Her proposals—such as regularizing job hires and providing free student transportation—are dismissed as unrealistic, with the group branding her campaign as “desperate” and based on populist appeals that are financially and administratively unsustainable.

The group also scrutinizes the wealth of both Jamjam and Love-Love, suggesting their public service salaries could not reasonably account for their reported lifestyles.

Their ownership of luxury vehicles, upscale properties and high-end accessories is presented as further evidence of corruption or unexplained enrichment.

Betrayals and backroom deals

The Movement for Transparency and Good Governance further expands its campaign by questioning the political affiliations and motives behind the Baronda-Mabilog-Sulong Gugma alliance.

The group’s content strongly suggests that, despite public denials, Rep. Baronda and Team Sulong Gugma are tacitly endorsing mayoral candidate Roland Magahin.

These claims emerged after Treñas alleged that Team Sulong Gugma is backing Magahin—an act he said violates the gentleman’s agreement brokered by House Speaker Martin Romualdez to prevent a fractured local race.

To support this claim, the group points to photographs of Magahin posing with Sulong Gugma campaign tarpaulins, his use of the party’s recognizable “finger heart” symbol and his appearances on a blocktime radio program hosted by Jun Capulot, a Sulong Gugma candidate.

These visuals are presented as circumstantial evidence of covert collaboration between Magahin and Sulong Gugma, despite the group’s official claim of neutrality.

Though Sulong Gugma denied the endorsement, Treñas vowed to raise the matter with the Speaker after the elections.

Treñas, Ganzon as top targets

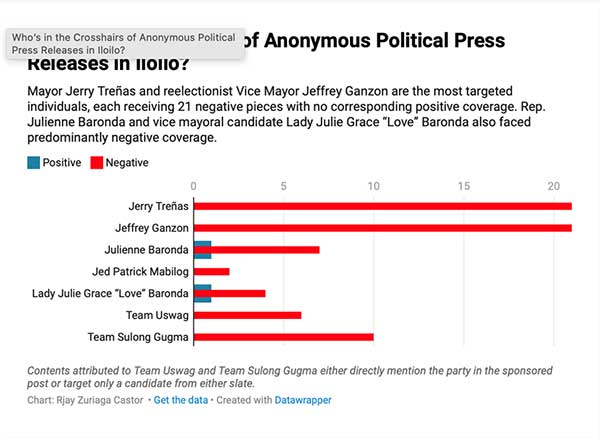

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/GJv6o/?v=3

The wave of sponsored posts is targeting Treñas and Ganzon, who have emerged as the most frequent subjects of negative coverage.

The Baronda sisters, both aligned with Team Sulong Gugma, were also subjected to predominantly negative coverage.

Even political slates were not spared, with some content suggesting an effort to taint entire parties through their association with specific councilor candidates.

Mabilog, whose name remains closely linked to the Baronda camp, was likewise not spared from negative attacks.

Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Gaps

Republic Act No. 9006, known as the Fair Election Act, ensures fair and nondiscriminatory elections. The law protects candidates from harassment and discrimination during the election period.

For the 2025 midterm elections, the Commission on Elections (Comelec) promulgated Resolution No. 11116 in February, which penalizes bullying and discrimination against candidates and supporters during campaigns—including acts based on gender, disability and other protected characteristics.

Violations are considered election offenses and can lead to disqualification and legal action.

Comelec has also implemented strict rules to ensure transparency in political advertising for the 2025 elections, including clear labeling and disclosures, especially for digital campaigns.

Under Comelec Resolution No. 11064, all official digital campaign platforms—such as social media accounts, websites and podcasts—must be registered with Comelec within 30 days after the filing of certificates of candidacy.

This registration aims to promote transparency and accountability in campaign activities.

Media and news organizations are also required by Comelec to disclose election advertisements and report the expenditures of candidates who air these ads.

Comelec Chairman George Erwin Garcia said newspapers, television and radio stations must properly report how much candidates spend on campaign advertisements, including full disclosure of contracts with candidates.

“Our only goal is truthful news and reporting on the actual expenses of candidates and party-lists in their stations,” Garcia said in a February interview.

“Don’t settle with two contracts—a legitimate contract, while the other one is not. I believe that the stations will not allow that,” he added.

Failure to disclose such expenditures can result in election offenses, including imprisonment of one to six years for responsible media officials.

Comelec Resolution No. 11109 governs campaign finance disclosure, requiring candidates and party-lists to file Statements of Contributions and Expenditures (SOCEs) within 30 days after the elections. These must include all forms of advertising—print, broadcast and internet.

Shadow Campaign Persists

Despite the regulatory safeguards of Comelec, loopholes remain—particularly when campaign content is funded by unnamed individuals or shell groups.

These opaque funding sources complicate efforts to trace who is financing political ads and for what purpose, especially as local races tighten and online narratives intensify.

The lack of accountability—no contact details, physical offices or known funders—suggests that these “groups” may be shell fronts for partisan actors using public relations tools as political weapons.

While it remains unclear who is behind these efforts, the volume, coordination and content strategy suggest a shadow propaganda campaign—one that leverages the credibility of traditional media and the reach of social platforms to shape public opinion “on air” and “off the record.”

The paid posts reflect not just campaign tactics, but a fragmented information ecosystem in which loosely named groups can influence the electoral narrative without facing scrutiny.