By The Institute of Contemporary Economics

First of two parts

There is generally no one single cause that can be attributed to as causing a specific road traffic incident. Too often the focus is on which among the personalities or objects involved in the incident is at fault. Sadly, investigations often end there. In many cases, there needs to be a deeper understanding of these incidents. And it can get complicated.

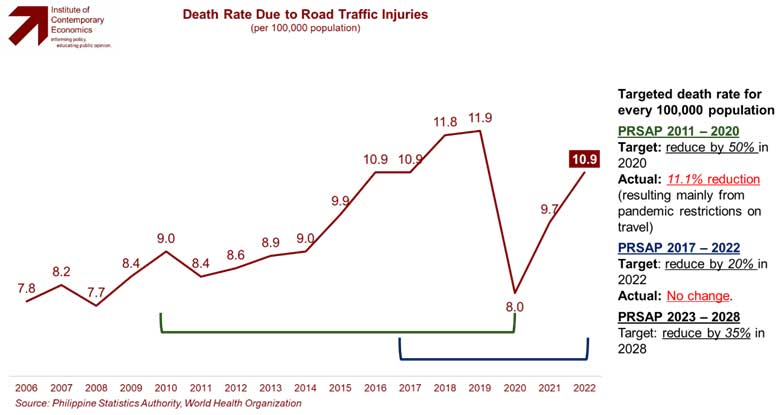

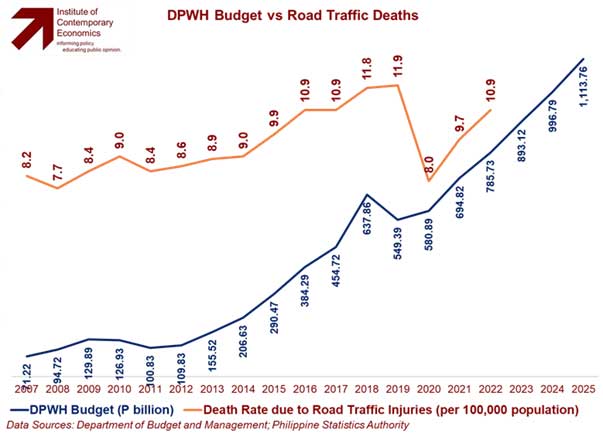

This report tries to shed light on other factors that weigh in on the rising death rate due to road traffic injuries in the Philippines. After expectedly tapering off during the pandemic years, the latest data show that the death rate has risen up to 10.9 deaths per 100,000 population (2022) caused by road traffic injuries.

The Philippine government is now in the midst of implementing the Philippine Road Safety Action Plan (PRSAP) 2023 – 2028. The target of the government is to reduce the death rate to 4.0 deaths per 100,000. Reaching this goal will be a significant challenge. In the 15 years of data that we have reviewed, the lowest figure we attained was 7.7 deaths per 100,000 in 2008.

It’s complicated but how…

A standard definition of the word complicated usually includes the following:

- Difficult to understand; and,

- Consisting of parts intricately related or combined.

The problem of road safety (or more appropriately, unsafe roads) is not that difficult to understand. It does have a lot of intricately related components. It is this that makes solutions complicated.

In the literature that we have reviewed, the Philippine government (as with many other countries) sets the goal of road safety as being the reduction of deaths due to road traffic injuries. This goal implicitly accepts that road traffic injuries will happen. It can be argued that a higher goal would be to prevent road traffic injuries (ergo adverse road traffic incidents) from happening at all. After all safety is designed as the absence of risk or danger.

Much has been studied and written about road safety and how to achieve it. Given this wealth of resources, knowing the factors that contribute to poor road safety in the Philippines that complicated.

As with many things in this country, knowing about the problem and actually fixing it are two different things. This where the complication lies.

The Philippine Road Safety Action Plan (PRSAP)

It has been difficult to accept at face value any “Roadmap” or “Action Plan” produced by any agency of the Philippine Government. Launched with great fanfare, most (if not all) of these plans fail to achieve their stated goals.

Why they have failed

Plans typically go awry and fall short of their targeted outcomes when:

- The targets are too ambitious;

- Underlying actions to meet target are not completed (or not done at

all);

- Action steps are vague and/or do not contribute towards tangible and meaningful results;

- Some unforeseen factor causes a change in underlying planning and implementation environment; and/or,

- There is a lack of the ability to adjust and adapt.

PRSAP 2023-2028 is the third iteration of this planning document. Our review of the failure (see chart) of the previous two PRSAPs to achieve their targets belie a combination of at least four of the five causes of possible failure.

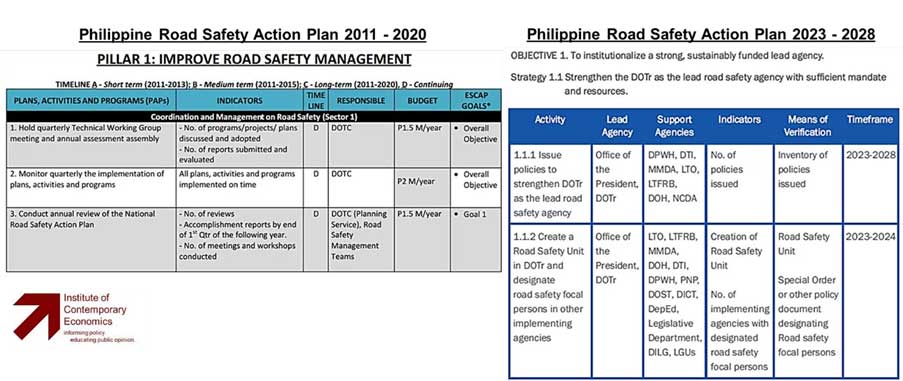

Checklists, checklists and more checklists

Checklists are one way of moving things forward by regularly reviewing the progress of the items contained in the checklist. For these to be effective, however, they need to include quantified outcome measures as a measure of progress. The listing of things on a checklist will not be sufficient to get things done.

The checklists contained in the PRSAPs are quite weak relative to pushing accountable actions in pursuit of the goal of improving road safety (see table on previous page). There is an inordinate number of actions specifying new policies and not enough attention being given to reviewing compliance with existing policies and regulations. As the saying goes, we don’t need new laws, we just need to implement the ones we already have.

Not learning from past lessons A look back at the PRSAP for 2011 – 2020 shows many actions listed in the checklist not having been done or at the very least, not having the desired impact. This is a pity as many of the action items identified are good ideas which are worth pursuing.

Subsequent PRSAPs contain only a passing review of the success of the previous PRSAPs. We have not seen an analysis of what has worked and what has not. The result is that the PRSAPs do not build on the lessons from its previous iterations. As a result, it would seem like every new plan substantively starts from square one every time.

Going beyond the kamote driver

Road traffic accidents are routinely attributed to the actions of drivers, pedestrians and even dogs who suddenly cross roadways. It is rare that bad road design or construction is blamed for these accidents.

The Department for Transport of the UK has been transitioning to a new framework of recording road casualty statistics with its road safety statistics team using the new framework for its 2023 statistics. The current framework coined Road Safety Factors (RSF) is meant to align with the Five Pillars of the UN Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021 – 2030.

Prior to this, the UK was using what was called the Contributory Factors (CF) for reported road casualty statistics. These CFs were meant to provide some insight into why and how road collisions occur. They were designed to give the key actions and failures that led directly to the actual impact to aid investigation of how collisions might be prevented.

Under the RSF framework the CFs were basically subsumed into the new recording methodology or eliminated altogether. One of the main reasons for the elimination of the old CFs was that they did not happen enough to justify recording or be of significant value to safety improvements.

It helps to look back at the CFs to see what apply to our situation in the Philippines. These road-related contributory factors for road casualties included:

- Poor or defective road surface

- Deposit on road (e.g. oil, mud, chippings)

- Slippery road (due to weather)

- Inadequate or masked signs or road markings

- Defective traffic signals

- Traffic calming (e.g. road humps, chicane)

- Temporary road layout (e.g. contraflow)

- Road layout (e.g. bend, hill, narrow road)

- Animal or object in carriageway

- Slippery inspection cover or road marking

- Stationary or parked vehicle(s)

- Vegetation

- Buildings, road signs, street furniture

- Dazzling sun

- Rain, sleet, snow, or fog

- Spray from other vehicles

Most of these also contribute to road accidents in the Philippines. It is helpful to remember, at this point, is that these CF data are collected as an input into weaknesses in road safety and the improvement thereof. This is quite different in our country where some of these CFs are taken as “normal” and nothing is done to eliminate these factors in improving road safety.

Human behavior in road safety

A careful examination of available data would indicate that human behavior accounts for the overwhelming (>90%) factor in road accidents in developed countries. This is the natural impact of well-designed infrastructure.

While the opposite should be true in less developed countries given the relatively poor state of their infrastructure, data is seldom collected on non-human factors in road accidents in these countries. The sad result of this is the “normalization” of bad roadway designs and construction. It doesn’t have to be this way

While human behavior and road infrastructure both contribute to road traffic incidents, we focus here on the latter.

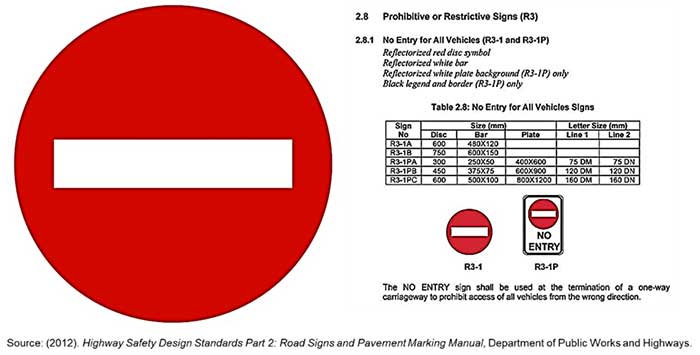

The Department of Public Works and Highways actually has a good manual on road safety contained in its Highway Safety Design Standards. It is a well-thought-of manual which covers road safety design, road safety planning design and risk assessment. The second part of the manual contains the specifications of road signs and pavement markings and instructions as to where and how these should be used.

Even a cursory examination of our existing roadways and assessing their compliance with the DPWH’s own safety design standards would lead one to conclude that very few of there are “up to spec”.

The inadequacy of oversight and lack of accountability

When a project ends up not following standards, it can either be that the original design itself was not compliant, or a contractor failed to meet the specifications of the project design.

DPWH Department Order (DO) 166 Series of 2024 lays out the guidelines for the issuance of the Certificate of Completion and Certificate of Acceptance for Locally Funded Projects. The DO is quite thorough and should be sufficient as a basis for the process of accepting completed projects.

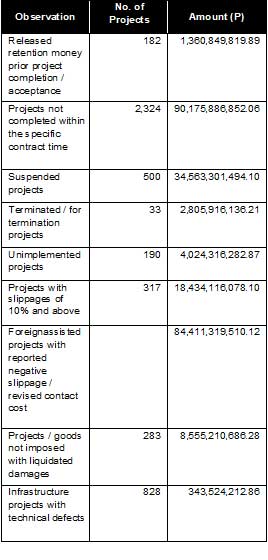

We reviewed the 2023 Consolidated Annual

Audit Report of DPWH as undertaken by the Commission on Audit. In the Report, we find many troubling audit observations which may obliquely shed light on the DPWH’s performance in undertaking its projects.

Specific details provided by CoA of deficiencies do not provide comfort. This includes comments such as:

“Scaling, cracks, damage (sic) structures, and/or items of works which were deficient or not in accordance with the standard specifications of the contract”

“The program of work of infrastructure project did not cover at least a usable portion of the projects and construction had been started for the portion of the project that is less usable, thus the project though 100% completed per program of work still remained idle and unusable”

“Completed infrastructure projects were unusable due to gaps in road component”

These CoA observations recur almost every year. Given that audits cannot cover the totality of an organization’s operations, it may be that there are a lot more of these that lie under the surface. It is also very rare to hear of sanctions imposed on those responsible for these defective projects. This has the effect of institutionalizing a culture that does not give importance to the proper use of the people’s money.

The table below shows a sampling of the audit observations of CoA on DPWH’s 2023 operations. These total P244.7 billion pesos worth of projects with issues accounting for just over 25% of DPWH’s budget for 2023.

The bottom line is that there is evidence that projects do get completed and get paid for despite not being completed according to DPWH’s standard. Despite this, the DPWH will get the lion’s share of the 2025 General Appropriations Act.

It is interesting to note, in light of the focus of this paper on road safety, that annual appropriations for DPWH somehow almost perfectly tracks the movement of the death rate in the Philippines due to road traffic injuries as seen in the chart that follows.

Creating problems

It is indeed disheartening to note that some of the road projects that are undertaken create problems. As an example, we are all witness to the practice of constructing roads around utility poles. This makes the utility pole a hazard (where it was not) and encouraging parking on these newly built roads meant to be driven in. This is a prime example of the privatization of a public good where something that is meant for use by everyone is appropriated for parking space by the few.

Many newly built roads also are not equipped with the proper road signages and pavement markings. This actually goes with existing roads which continue to be left unsafe with the absences of these standard safety measures.

Finally, there are some roads which seem to ignore traffic engineering principles in terms of their design and how they impact the flow of traffic. This is not solely on the lap of DOWH as the lack of expertise and coordination on roadworks performed by local government units leads to badly designed projects leading to unintended consequences which could have been foreseen.

The other suspects The LTO

The other major component of road safety is the regulation of driver behavior. Road infrastructure, when done right, does serve a static role by guiding drivers via road signs and pavement markings.

In the Philippines, the regulation of driver behavior starts with the Land Transportation Office (LTO). Its mandate includes:

- The registration of motor vehicles;

- The issuance of driver’s licenses;

- The enforcement of traffic laws, rules and regulations; and,

- The adjudication of cases involving apprehended drivers.

The LTO in its current form traces its roots from Executive Orders 125, 125-A and 226, all issued in 1987. Before that, it was known as the Land Transportation Commission which also had, as part of its mandate, the franchising of public utility vehicles. This last responsibility has since been undertaken by the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board.

Even with the transfer of its public utility vehicle mandate, the LTO remains a unique creature in the transportation regulation environment. In the United States, for example, the registration of vehicles and issuance of drivers’ licenses is handled by the Department of Motor Vehicles overseen by state governments. Enforcement of traffic rules and regulations is typically done by local law enforcement agencies.

Given the wide scope of its responsibilities, it may be too much to ask of the LTO to perform these responsibilities in the most effective and efficient manner possible. While there has been significant improvement, particularly in the processing of drivers’ license renewals and new mandates attendant to new driver registration, there are areas such as the issuance of vehicle license plates which need significant improvement.

Its performance as the lead agency in enforcing traffic rules and regulations also needs significant attention. Recent incidents of road injuries and fatalities only shines a light on the need for major improvement.

It is clear that the LTO does devote or does not have enough resources to properly fulfill its mandate of enforcing traffic rules. Ideally, given its limited resources, this LTO needs to make more of an effort to deputize local government traffic enforcers.

It may have done so in some areas, the MMDA being a prime example, but its policy on deputizing local agencies has been inconsistent, at best.

The inadequate enforcement of traffic rules and regulations normalizes behavior that are violative of these regulations. Article V (Miscellaneous Traffic Rules) of Republic Act No. 4136 (Land Transportation and Traffic Code) lists down eight of the most basic traffic rules. Of this eight, most of us see four of them being violated (with little in the way of apprehension) on a regular basis. These include:

- Reckless driving;

- Hitching to a vehicle (e.g. riding on the roof of a jeepney);

- Driving or parking on a sidewalk; and,

- Obstruction of traffic.

One of the main problems with our traffic enforcement regime is that they are static in nature. Most violations, including the ones above, are moving violations.

Then there are other violations mentioned in RA 4136 contained in Article IV (Accessories of Motor Vehicles) that are not policed to the point that it becomes okay to break the rules. This includes the requirements for vehicle headlights, taillights, stop lights, etc. Since most of these can only be observed at night, the LTO does not catch them because they do not operate at night. The absence of headlights on public utility vehicles especially at night is an especially dangerous traffic hazard yet these have become a common sight on our roadways.

Finally, there is the seeming optionality in the use of motorcycle helmets in many rural and some urban areas.

The LTO performs a vital role in engendering road safety but if it fails in its various mandates, particularly in the enforcement of traffic rules and regulations, the best designed and constructed road infrastructure can only do so much in creating the safe transportation environment that is required to reduce road traffic deaths.

To give credit where credit is due, the LTO has produced a very useful driver’s manual which helps in educating current and aspiring drivers. This document is certainly a step in the right direction which needs to be more widely disseminated.

Local governments

“It is hereby declared the policy of the State that the territorial and political subdivisions of the State shall enjoy genuine and meaningful local autonomy to enable them to attain their fullest development as selfreliant communities and make them more effective partners in the attainment of national goals. Toward this end, the State shall provide for a more responsive and accountable local government structure instituted through a system of decentralization whereby local government units shall be given more powers, authority, responsibilities, and resources. The process of decentralization shall proceed from the national government to the local government units”.

– Republic Act 7160, Local Government

Code of 1991

Local governments play a critical role in the promotion and actualization of road safety. This begins with land use planning, which, with the enactment of the Local Government Code of 1991 was devolved to local governments.

The Institute for Local Government describes land use planning as “…the relationship between people and the land – more specifically, how the physical world is adapted, modified, or put to use for human purposes. This includes even the “non-use” of lands reserved as wilderness or protected from human impacts”.

Local planning is one of the most important responsibilities of local government officials. Planning, in this context, includes determining how land will be used, how to provide infrastructure and services to those uses.

The Local Government Code devolves land use planning authority consistent with the idea that local governments are in the best position to know and respond to the needs of their communities. Land use planning and community development impact the general health, safety, and welfare of residents of the locality. Economic vitality, environmental health and quality of life are all influenced by land use and community design decisions.

It is sad to note, however, that despite the policy statement of RA 7160, certain activities which can be argued as being within the proper ambit of local governments remains with the national government. This includes certain levers which contribute to road safety.

The grant of public utility franchises and the enforcement of traffic rules and regulations are among these levers that remain with national government institutions. While local governments originate plans for public transportation routes, approval of Local Public Transportation Route Plan (LPTRP) still rests with the Department of Transportation. This creates a condition where the approving authority may have less knowledge of local conditions compared to the local government officials who prepared and have responsibility for the implementation of the LPTRP.

We have also observed the inclination to convert city roads to national roads. The rationale is to offload the cost of maintaining and rehabilitating these streets to the national government.

This practice, however, deprives the city of the ability to fully control any modifications or improvements to these roads which have been transferred to the national government. It also can have the effect of delaying repair work for any damage to these roads as it will now have to rely on the availability of funds at the DPWH to initiate these repairs. We have witnessed this firsthand in the delayed rectification of the Ungka flyover which had to submit a budget to be included in a subsequent year GAA. In contrast, local governments have easier route to budget allocation by enacting a supplemental budget ordinance for unforeseen or emergency purposes.

This practice also does not conform with the original definition of roads based on their utility. The DPWH defines roads and describes the road hierarchy in the following manner:

Road network is defined as a hierarchy in terms of road types and according to the major functions it will serve.

The main classification is whether the road is to be used primarily for movement or for access.

An expressway is proposed for a road corridor under the following situations;

- A road corridor connecting several highly urbanized centers with ribbon-type of development of commercial, business and industrial establishment.

- A road corridor with high traffic demand.

These roads are the longer distance transport routes for motorized traffic. They provide the transportation link between regions and provinces. Their primary function is movement and not access.

National Roads are roads continuous in extent that form part of the main trunk line system; all roads leading to national ports, national seaports, parks or coast-to-coast roads. National arterial roads are classified into three groups from the viewpoint of function, i.e. North-south backbone, EastWest Laterals and Other Strategic Roads.

Provincial Roads are roads connecting one municipality with another; all roads extending from a municipality or from a provincial or national roads to a public wharf or railway station; and any other road to be designated as such by the Sangguniang Panlalalwigan.

City Roads – these roads/ streets within the urban area of the city to be designated as such by the Sangguniang Panglungsod.

Municipal Roads – these roads / streets within the poblacion area of a municipality to be designated as such by the Sangguniang Bayan.

City I Municipal Roads serve to feed traffic onto and off the main road network at the beginning and end of trips. These roads serve local traffic only.

Barangay Roads are rural roads located either outside the urban area of city or outside industrial, commercial or residential subdivisions which act as feeder farm-to-market roads, and which are not otherwise classified as national, provincial, city or municipal roads. Roads located outside the Poblacion area of a municipality, and those roads located outside the urban area of a city to be designated as such by the Barangay Council concerned.

Pedestrianized Areas/Routes These are areas from which all motorized vehicles are excluded to improve safety. In their broadest sense they would include all routes where nonmotorized traffic has sole priority. This would include purpose-built footpaths and bikeways that often form a totally separate network to that for motorized traffic in residential areas.

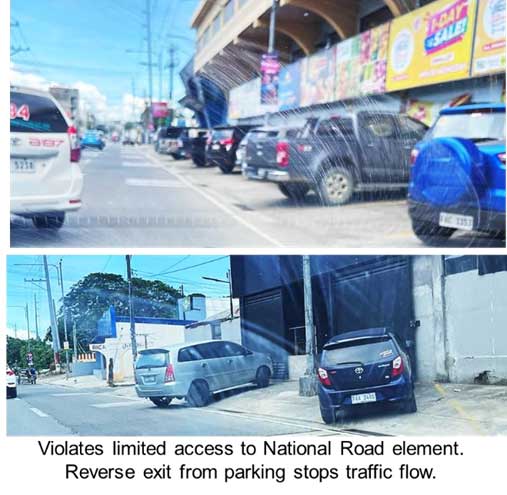

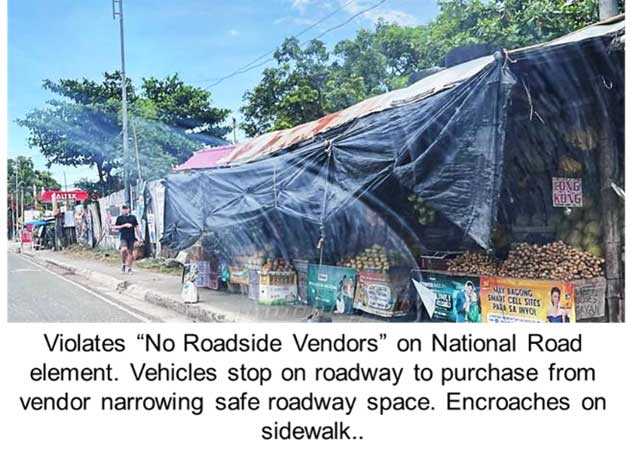

Further, the DPWH lists down elements of a national road which include:

- Limited frontage access

- Development set well back from the highway;

- All access to premises provided via provincial roads;

- Number of intersections to be minimized;

- Suitable at-grade channelized intersections for minor flows and other elements

- No roadside vendors.

Bearing these elements in mind, these are some of the streets in Iloilo City that are tagged as national roads:

- Rizal St. (City Proper)

- Rosario-Duran

- Delgado St.

- Jalandoni St. in City Proper

- San Rafael Road to Tabucan road

- Timawa Avenue

- Molo Boulevard

- Jereos St.

- Cubay road to Balabago road

- Tacas road from Quintin Salas, Jaro to Pavia boundary

- Rizal St. (Jaro)

- Loboc road to PPA

- Yulo Drive

- Arevalo-So-oc. Mandurriao road

- Bonifacio Drive (Arevalo)

- the whole stretch from Carpenter’s Bridge to Diversion Road Efrain B. Treñas Boulevard

- Iznart to Rizal St.

- Fuentes St.

- Valeria St.

- Luna to Jalandoni St.

- Quezon St. Arguelles St.

- Democracia St.

- Cuartero St. Loboc to La Granja road

The conversion of these streets to national roads was properly consummated via an act of Congress and approved by the President at the time that these laws were passed.

Despite this, all of these streets do not comply with the elements required of national roads. To be clear, laws supersede standards developed by any agency of government. Nevertheless, these standards were developed by professionals using guidelines meant to ensure road safety and efficiency of use. The conversion of these streets by law now created confusion which defeats the purpose of having standards. This is not unique to Iloilo City and is a practice that is prevalent via Congressional fiat.

To complete this picture, the elements for city/municipal roads are as follows:

- The road is only for local traffic; through traffic is adequately accommodated on an alternative more direct main road;

- Where possible, an industrial traffic route should not pass through a residential area;

- Vehicle speeds should be kept low so long straight roads should be avoided;

- Parking is allowed, but alternative off-road provision should be made if possible;

- Non-motorized traffic is of equal importance to motor traffic and separate route should be provided if possible;

- Where non-motorized traffic needs to use a local distributor, it should be separated from motorized traffic;

- The road width can be varied to provide for parking or to give emphasis to crossing points depending upon traffic flows;

- Bus stops and other loading areas (only permitted in exceptional circumstances} should be in

separate well-designed lay-bys;

- Through-movements should be made awkward and inconvenient to discourage them; and,

- No roadside vendors.

Given the marked differences in the standards between national and city roads, which of these should now apply to the newly converted national roads? As it was, these city streets were already not up to standard and continue to be so.

Whatever the case may be (and the confusion that they so for developmental purposes), the way forward should be to design and institute remedial measures to improve the safety of these roads based on the current their use. In a previous report, we alluded to the 2004 JICA Study for Road Network Improvements. Many of its unimplemented recommendations remain applicable todays as they did then. We encourage a review of these recommendations and their implementation.

Policy Directions

“If we just follow everything that we write including the laws that we pass, the guidelines that we set, the Philippines would have been a First World country a long time ago”. – Anonymous

This quote pretty much sums up why we are the state we are in. This goes for the reason why 33 (and growing) people die from preventable injuries from road traffic incidents.

The Philippines has committed to Vision Zero which aims to create a worldwide road transport system where no person dies or is seriously injured from road traffic incidents. PRDP 2023-2028 sets an intermediate goal of 21 people dying every day from these avoidable incidents by 2028.

If the Philippines were to make significant inroads into the Vision Zero goal it will have to make many difficult changes and shifts in policy direction. This would include:

- Reallocating the majority of the annual General Appropriations Act budgets towards road and land transport infrastructure remediation at the expense of new road construction.

- Following existing DPWH standards in infrastructure remediation and in whatever new road construction.

- Enacting a law creating a Road Transport Safety office consolidating within one entity all aspects of Transportation Safety policymaking and oversight. This should expand the scope of the Philippine Transport Safety Bill which was vetoed by President Marcos.

- Removing the traffic enforcement mandate of the LTO and transferring this function to the Philippine National Police and local traffic enforcement.

For Iloilo City, policy directions and actions should include:

- Total rethinking of the LPTRP with a view towards aligning it with best practices in urban planning.

- Re-starting plans for a long-term solution to public and mass transportation.

- Revamping the current traffic management body to take on more policymaking and coordination roles and improving traffic rules and regulation enforcement.

- Audit of road and traffic infrastructure and instituting measures to improve road safety.

- Act on “low hanging fruit” such as:

o Consistent apprehension of violators of simple regulations such as:

-No Parking

-No Parking on Sidewalks

-Traffic Obstruction by PUVs from improper loading / unloading of passengers

-Illegal structures on roadways and sidewalks

o Consistent application of requirement for Traffic Impact Assessment for new building construction. o Issuance of new building permits contingent on consistency with standards of development along national roads such as:

-Limited frontage access; and,

-Development set well back from the highway.

o Enacting an ordinance providing a time frame for current structures not in compliance with roadway development standards to comply.

We have always contended that Iloilo and Iloilo City have the knowledge, ability and resources to tackle and solve seemingly intractable and persistent problems. Yet this has to start with acknowledging that there are these problems, mobilizing resources to fix these problems and actually doing it. (To be concluded)