By Sensei Adorador

Does the blame for our current literacy crisis lie solely with the Department of Education (DepEd)?

This was a question posed by one of my students during a recent lecture on the state of literacy in the Philippines.

The honest answer is no—it is not just DepEd that bears responsibility.

The issue is systemic, rooted in both national and local governance.

There is an African proverb that says, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

This emphasizes the collective responsibility of a community in nurturing its members.

In the Filipino context, this resonates with the indigenous concept of kapwa, a value system that highlights shared identity, interconnectedness, and mutual responsibility.

If we accept that learning is a communal enterprise, then it is only logical to look beyond the classroom and consider the broader ecosystem that influences a child’s capacity to learn.

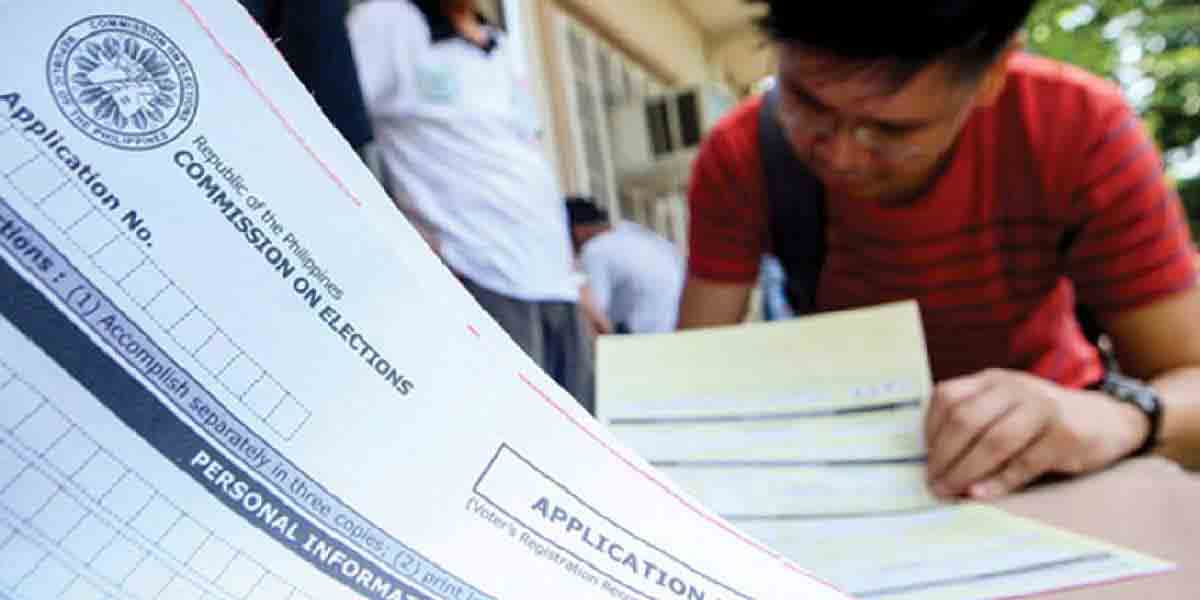

The first layer of this issue involves our political choices.

The leaders we elect have a critical role in shaping education policy.

We must choose leaders who genuinely champion education, particularly early childhood education.

Lawmakers and executives at both local and national levels must prioritize the needs of children—not their political survival or personal gain.

Unfortunately, many voters remain trapped in a cycle of short-term thinking, electing the same kinds of leaders who promise change but deliver the same corrupt practices.

This myopic approach to elections perpetuates systemic dysfunction, including in the education sector.

Another layer involves the structural support—or lack thereof—for Child Development Workers (CDWs).

Are they given sufficient training to unlock the potential of the children they serve?

Do they work in environments conducive to early learning?

The findings of EDCOM II revealed a dire shortage of pre-kindergarten facilities, despite research affirming the critical importance of early childhood development (Heckman, 2011).

Without adequate early intervention, children are at a disadvantage before they even begin formal schooling.

We must also confront the issue of food security.

Proper nutrition is foundational to cognitive development.

How can we expect children to concentrate in class when they arrive at school hungry?

I recall countless students who came to school without breakfast—many of them listless, inattentive, and unable to participate.

This is not just anecdotal; neuroscience and developmental psychology consistently show that malnutrition affects brain development and learning capacity (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007).

In terms of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, if a child’s physiological needs are unmet, how can we expect them to fulfill higher-level cognitive tasks like reading comprehension or critical thinking?

This brings us to another failure: the inability of the education system to consider preexisting conditions that hinder learning.

Changes to the curriculum, no matter how well-intentioned, are futile if we ignore the underlying issues that impair student readiness.

A new set of learning competencies cannot compensate for an empty stomach or an uninspired, undertrained teacher.

Moreover, we are now contending with an even more insidious challenge—digital distraction.

Today’s learners are immersed in virtual content: TikTok, YouTube Shorts, online gaming, and algorithmically curated media.

These platforms, while entertaining, have rewired our students’ cognitive habits.

The result? A generation of children who can decode words but fail to grasp meaning—readers without comprehension.

As a teacher, I see this daily: students can recite beautifully like parrots but struggle to explain what they have read.

This issue is rooted in poor reading instruction at the elementary level, which snowballs into deeper deficiencies in high school and college.

A strong foundation in early literacy is crucial.

If this is not addressed, college students will continue to rely on artificial intelligence tools to generate essays without understanding the underlying arguments.

This affects not only their academic performance but also their ability to synthesize information, participate in civic discourse, and engage in democratic processes.

Ultimately, this literacy crisis is not merely an educational issue—it is a social and moral one.

Are we still practicing kapwa?

Or have we retreated into individualism, indifferent to the struggles of our fellow Filipinos?

We cannot claim to value kapwa while tolerating systems that rob children of their futures.

The government, particularly DepEd, must work in tandem with other sectors to address the roots of illiteracy: poverty, poor nutrition, lack of facilities, and weak teacher training.

But this also calls for a renewed sense of civic responsibility.

We must elect leaders who prioritize education, food security, and child welfare—not just as campaign slogans but as actionable commitments.

As we face a rapidly changing world, filled with new technologies and complex social challenges, we need to prepare the next generation with more than just functional literacy.

We need to nurture critical thinkers, empathetic citizens, and lifelong learners.

The time to act is now—not just for the sake of the children in our classrooms, but for the future of our shared kapwa.

About the Author

Sensei M. Adorador is a faculty member at the College of Education, Carlos Hilado Memorial State University.

He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in Psychology, with a specialization in Social Psychology, at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

He is also a member of CONTEND (Congress of Teachers and Educators for Nationalism and Democracy).