In a province known for intense political contests, shifting alliances, and families who treat local offices as inheritances, Cabatuan, Iloilo is oddly calm.

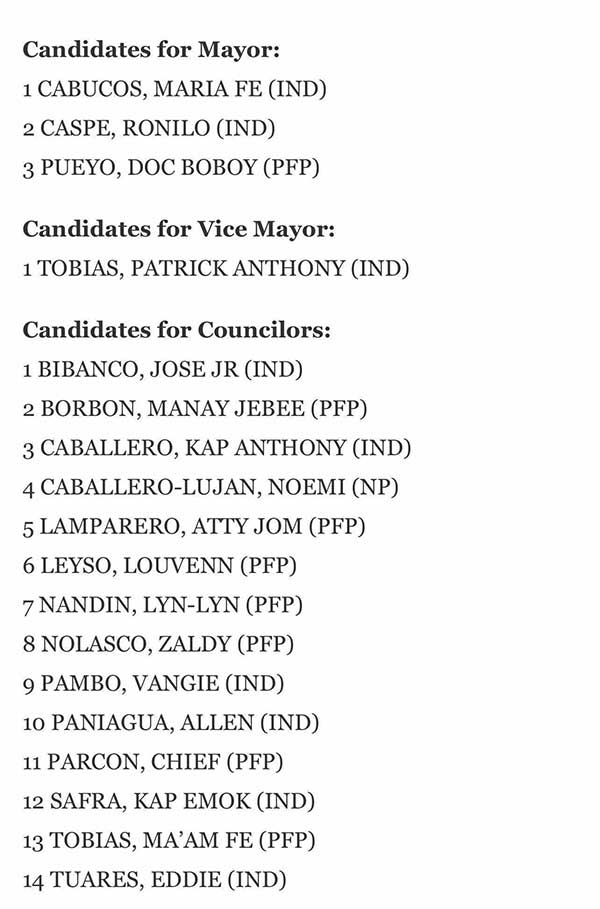

With just three mayoral candidates—two of them independents—and a lone bet for vice mayor, the 2025 local elections in this central Iloilo town barely register a pulse.

The race for council seats is similarly subdued. Fourteen candidates are vying for eight slots, but with no monolithic party banner dominating the list. Only the Partido Federal ng Pilipinas (PFP) appears to have fielded a partial slate. Most others are running independently, suggesting a lack of political consolidation.

This quiet isn’t just procedural—it feels cultural.

Unlike other Iloilo towns where politics is a sport of survival, spectacle, and supremacy, Cabatuan seems to be holding its breath.

And this raises the question: is the town maturing politically, or is it simply tired?

There are two competing narratives. One, more hopeful, sees the absence of political dynasties as a sign of progress. Without entrenched clans dictating the pace, the field opens to newcomers—civic-minded individuals without access to vast machinery or deep pockets.

In this light, Cabatuan could be an example of a community slowly dismantling patronage politics in favor of merit and independence.

The other narrative is less romantic. It suggests disinterest. A kind of political boredom or even cynicism that keeps new leaders from rising and voters from caring.

The unopposed vice mayoral bid and the scattered affiliations may signal that residents are disengaged—not because they are satisfied, but because they no longer believe change will come from the ballot box.

Cabatuan’s voters are not unfamiliar with broken promises. Like many towns, it has seen project delays, unmet infrastructure plans, and health or social services that struggle to reach the grassroots. But unlike places that respond with protest or populism, Cabatuan seems to have gone silent.

The silence could also mean something else: absence of political investment. Without the presence of power brokers or kingmakers, elections don’t have the usual pageantry, mudslinging, or mobilization. It’s democracy, but stripped of drama.

Whether this is a sign of political evolution or regression depends on what follows.

But if voter turnout dwindles, and elected leaders win on sheer default, then the town risks sliding into administrative inertia. Without public pressure, even the most well-meaning independent candidate can grow complacent. And without vision, even a dynasty-free LGU can stagnate.

The future of Cabatuan lies not in who wins the May elections, but in how its citizens treat the post-election period.

Will they treat public service as something to monitor, evaluate, and demand? Or will they retreat into quiet discontent, leaving local affairs to unfold without them?

For now, the town stands out—not for its noise, but for its stillness. And as with any silence, it is what follows that will tell us what it truly meant.