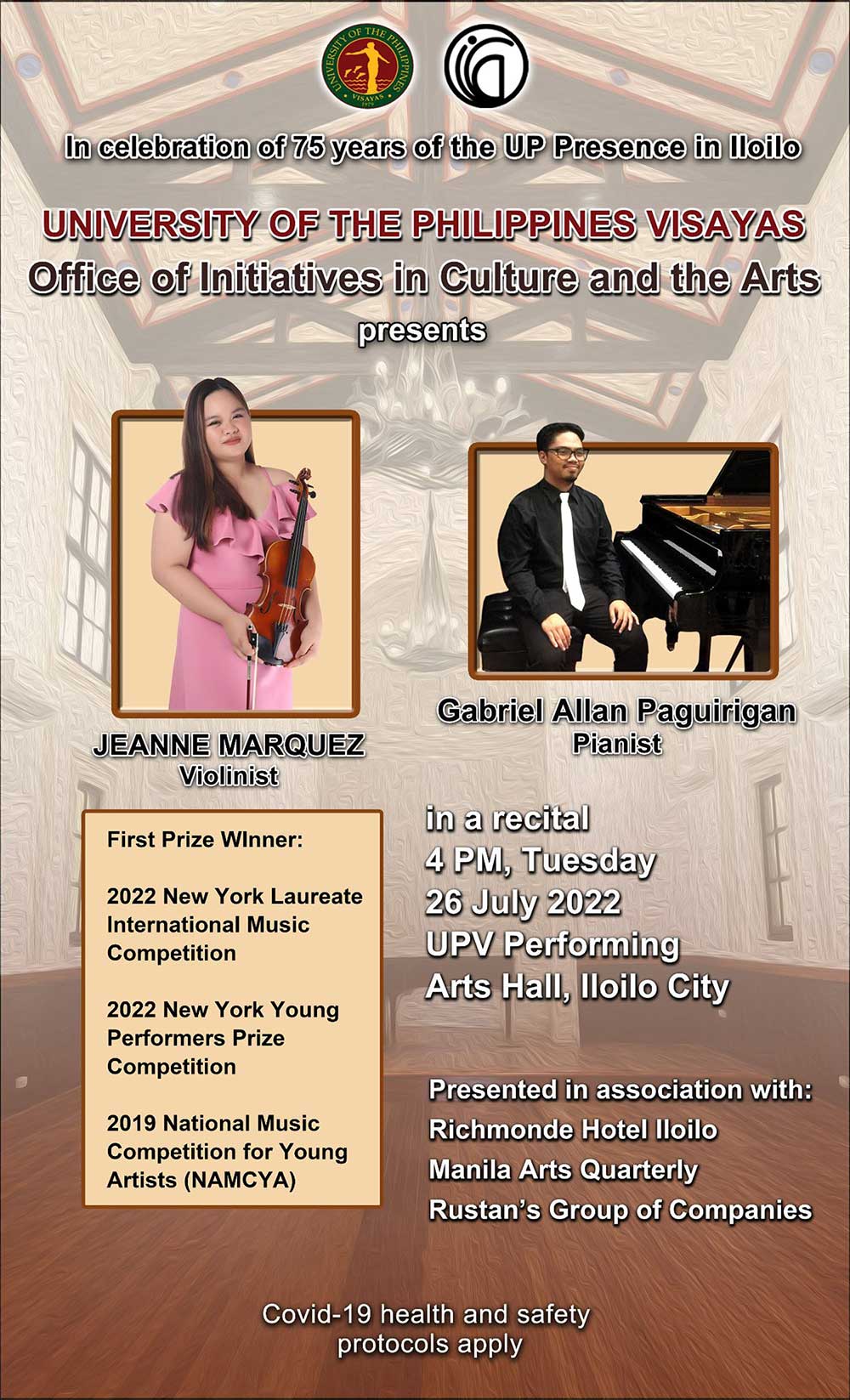

By John Anthony Estolloso and Miguel Antonio Davao

Last July 26, the University of the Philippines – Visayas’ Performing Arts Hall witnessed a musical extravaganza seldom seen in this city. Granted, it was but a recital in a rather condensed hall of classical dimensions and designs, yet it did provide an apt setting for two promising musicians who somehow rekindled stale classics with the veneer of masterful interpretations.

In a nutshell, Jeanne Marquez’s performance was exhilarating: she displayed a musical expertise relatively prodigious at her age and an understanding of the violin that is rare among musicians of her generation. Second to none would be Gabriel Allan Paguirigan’s piano accompaniment to the soloist: intuitive, intense, and introspective. His exquisite control and phrasing – aptly played legatos and rubatos – that caught on with the sigh and strain of the soloist, complemented the plaintive playing of Marquez, even as it reminded the audience that, yes, the piano was still the ‘bigger’ instrument.

Their rendition of Carlos Gardel’s ‘Por Una Cabeza’ (made fatuously popular by the 1992 film ‘Scent of a Woman’) as arranged by film composer John Williams stayed true to the spirit of the arranger. The title itself is a Spanish horse racing expression that is used when a contender won “by a head” – which mirrored precisely the performance of the two musicians. Just when the listener felt like they were getting ahead of each other, they win this piece by keeping their audience at the edge of their seats with explosive pizzicatos, spicy arpeggios, and the occasional rubato that comes at the most opportune times only to surprise the acutely discerning with something out of the blue.

Camille Saint-Saëns’ fiendishly difficult Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso is one that most conservatory students avoid. Not for Marquez and Paguirigan. The former especially gave off an electric musical sizzle to the audience each time she is given the limelight to show off alone in some segments. Her consistent trills and flying staccatos were something that would have been only achieved by a 40-hour per day practice (if you get the social media reference) – or something close to that.

On a more serious note, the ending cadenza of this hefty piece was the highwater mark of the performance, as it really showcased Marquez’s virtuosity – as a good cadenza should. Although written out by Saint-Saëns himself, her performance of this tricky passage prior to the dazzling finale was a feat in itself.

To the regular listener, Beethoven’s music is lugubrious, tedious, and a tad ostentatious: it would seem that the deaf maestro must insist that everyone knows by his music that he is deaf – and has to deal with his handicapped genius, even in our times.

Somehow, none of that surfaced in Marquez’s rendition of his Sonata for Violin in C Minor. Instead, the contrast of musical colors burst from the passages that range from the lyrical to the thunderous, from delicate running scales to fluttering thrills and ritornelli. All in all, there was bravura but no pretension in the execution.

Perhaps it has something to do with Beethoven’s deliberate deviation from the conventions of the sonata form, thus giving Marquez a musical podium to showcase contrasts: the allegro set against the cantabile even as the racy, rollicking presto of the finale ensured a rousing applause from a delighted audience.

To cap the Romantic repertoire was a reduction of Felix Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E Minor. Albeit the absence of an orchestra, Paguirigan’s zesty and thundering piano reduction was powerful enough to drive home the zeitgeist of the composition – a century of revolution, when all manner of things mundane are magnified through rose-colored lenses.

Most striking from the composition was the andante: it was poignant with a puissant dreaminess reminiscent of the composer’s lyrical melodies – indeed, a song without words. Marquez exhibited the technical mastery so yearned for by the composers of that age, that is, to flaunt and push the limits of the instrument, even to the point of overshadowing the performer.

Yet she was not overshadowed. Her lyric andante quickly shifted to the allegretto non troppo of the finale (thus happily depriving the lost among the audience a chance to applaud between movements); the molto vivace of the closing bars maintained her technical command of the instrument, with the elegant and subtle phrasing so consistently employed throughout the recital. The standing ovation that ensued was indeed well-deserved.

The encore pieces reverted to the comfortably familiar – and Ms. Marquez and Mr. Paguirigan did not fail to deliver. There was Nicanor Abelardo’s ‘Cavatina’, a sad, tender composition that just gets more beautiful each time it is performed. Jules Massenet’s ‘Meditation’ from ‘Thaïs’ was a rejuvenated staple, and what better way to end than with a reprise of Gardel’s ‘Por Una Cabeza’? Then again, what else can put blissful smiles on an appreciative audience at the close of a violin and piano recital than the faint memory of Al Pacino and Gabrielle Anwar gliding blindly across the dance floor?