By John Anthony S. Estolloso

KIP OEBANDA’S films always take the metaphorical cake, either as satire or biography – Bar Boys was funny enough as a cinematic retelling of what lawyers must go through to reach the bar and Liway was autobiography elevated to historical drama. Now he offers his audience something much tougher to chew and digest.

Balota is Oebanda’s satiric diatribe of Philippine politics. It has somehow transcended from the categorically comic and tragic, and melded both into a social commentary that is both laughable and deplorable: a mirror-image of our electoral realities. But such is the function of comedy – to make the audience see the absurdity of their own existential, social, or political states. We can laugh and curse at the exaggerated excess of face-splattered campaign ads shown in the cinematic screen precisely because we find the same hanging by the sidewalks of our city.

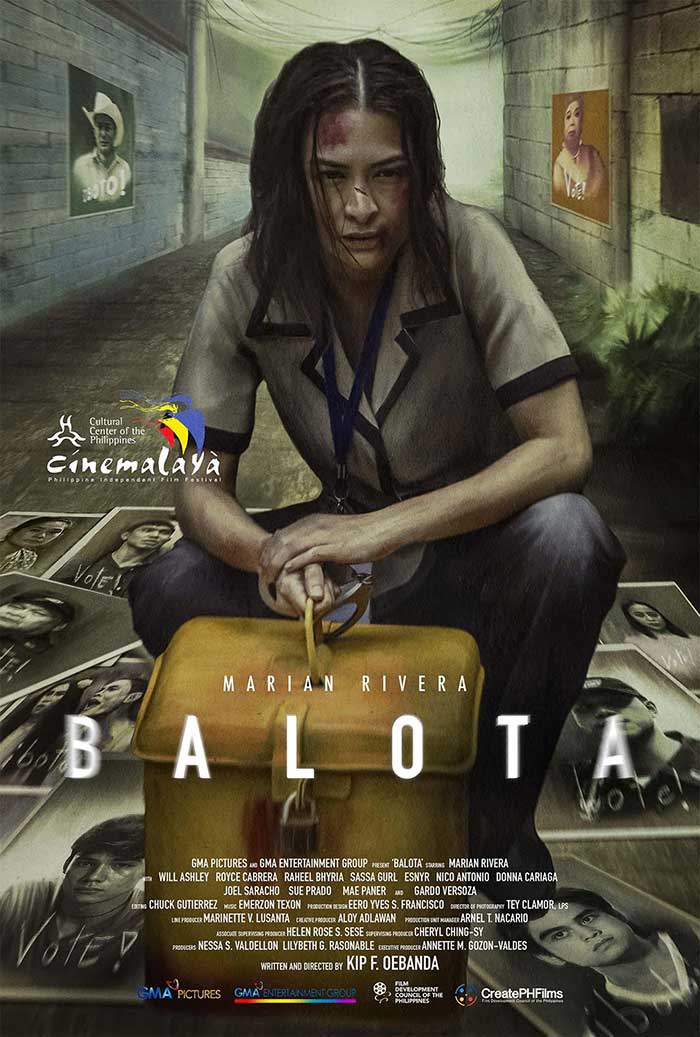

The plot is familiar enough, which makes it all the more worrying. A public school teacher on election duties gets waylaid at gunpoint as she delivers the ballot box entrusted to her; hounded by hired guns, she has to trek through hills and jungles with the cumbersome container chained to her wrist, only to find herself in a precarious position of becoming a pawn caught between two power-hungry politicians. Punctuated by murder and mayhem, the story inflates into a comedy of errors, redolent with layered political narratives and snide asides, ranging from very familiar house-to-house campaigns to brazen envelope distributions.

Characterization leans towards the overblown. Marian Rivera plays Teacher Emmy, one of those principled educators who somehow keep the public school system afloat through simple grit and sheer integrity – and how many of her kind are left in our schools? Perhaps the depiction is too idealistic, far from our simplistic image of teachers usually enmeshed in more domestic woes, like lesson plans and loans.

Mae Paner and Gardo Versoza as fatuous politicians hellbent on forwarding their personal interests in the name of public service, may be a tad bloated in portrayal. Paner as Hidalgo was all histrionics, something akin to an operatic diva singing the wrong part; Versoza as Edraline [glib reference noted!] oozes with an ego as swollen as the protuberance of his member, made more prominent by the recurring intrusions of his hand into the pocket of his pants. In any case, we have seen the likes of these politicians in the recent election.

The supporting characters are more believable. Joel Saracho as an abusive cop with murder in mind is terrifying to contemplate while Felix Petate and Esnyr Ranollo’s portrayal of the LGBTQ+’s role in awakening political consciousness from the grassroots did not go unnoticed. It is without duplicity that they affirm that our penchant for pageantry takes precedence over our politics: simple shows to win simple people.

For all of Balota’s exaggerations, the film unabashedly reveals the cracks running beneath the veneer of our traditional politics, one that relies more on token gestures than sincere intentions. When hitmen cross themselves before an assassination, should we not question if religion is still a moral force and not merely a spiritual placebo? When candidates win by jingles and jigs rather than well-planned platforms, should we not raise an eyebrow on the gullibility of the voters? When filthy rich politicians are catapulted into power by dirt-poor supporters, should we not be alarmed by this simple-minded credulity?

Beneath the dramatics of the actors, the film is a panegyric to the rotten hopelessness of Philippine politics: the tragedy of a failed democracy reenacted every other year and glorified by titling it with ‘fair elections.’ Much as we want to deny it, election time in this country sadly degenerates into a masquerade of bribery and violence, the machinery of corruption fueled by bread and the circus thrown at the masses. Keep the envelopes flowing, keep the cheap entertainment running, and no one would give a damn on who sits in office: the state dies by ballot box.

Balota will turn into a classic – not so much for of its cinematic cleverness and idealisms, but for its laconic and remorseless narrative that makes you want to curse like Teacher Emmy by the film’s end. But we need that: we need more films to make us curse and rage at the dying of the light.

[The writer is the Social Studies subject area coordinator of one of the private schools in the city. The poster of the film is from IMDb.]