By Martin Genodepa

Enlightened – the term means many things: knowledgeable, informed, educated, wise, or keen in spiritual things.

But before all these synonyms sprung, the word literally means to put light into something. Hence, the atmosphere courtesy of the dark and seemingly dank venue, wittingly or unwittingly, added another layer of meaning to Enlightened, the recent exhibition of paintings by Marzz Capanang, Charmaine Española, Bea Gison, MA Tuvilla, and Paul Fortunado at the Himbon Art Hub.

That the artists have seemed to have agreed on the grey-black-white color scheme for their works in keeping with the theme of enlightenment is at once a strength and a weakness. The weakness, although not exactly severe, stems from harnessing traditional color symbolisms to drive the group’s thematic agenda. The strength is derived from overcoming the limited use of color to create works that put forward what each artist exclusively wants to express or communicate.

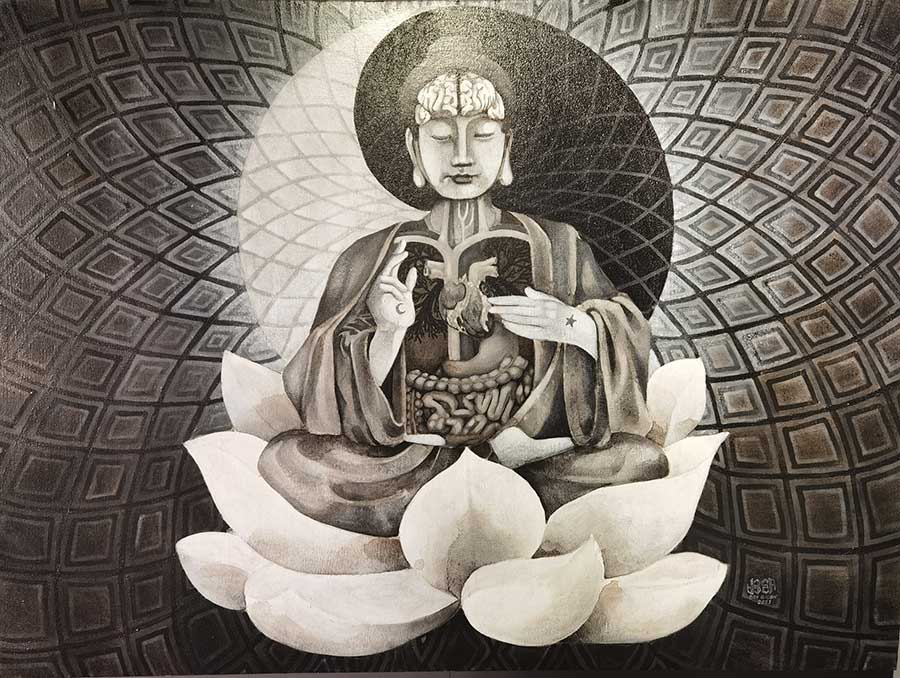

Homeostasis, Bea Gison’s installation of paintings primarily borrows from Buddhist iconography; Buddhism is, after all, is the purveyor of enlightenment. The large central painting of the seated Buddha with exposed vital organs is flanked by decorative small tondos of the lotus. Their repetitive variations are like mantras, reiterating the idea that the purity of mind and body is important to be truly enlightened. Betraying syncretism, the mudra of Buddha’s hands marked by a crescent moon (signifying womanhood) and a star (signifying humanity) is borrowed from Roman Catholic iconography, specifically the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

By exposing the seated Buddha’s brain, heart, and intestines, Gison is clarifying that matter or the body with the vital organs that compose it is important in spiritual enlightenment as it is where the spirit dwells.

The paintings of MA Tuvilla and Charmaine Española appear like confessions of enlightened or empowered women who have undergone some harrowing experiences and have struggled much but have overcome.

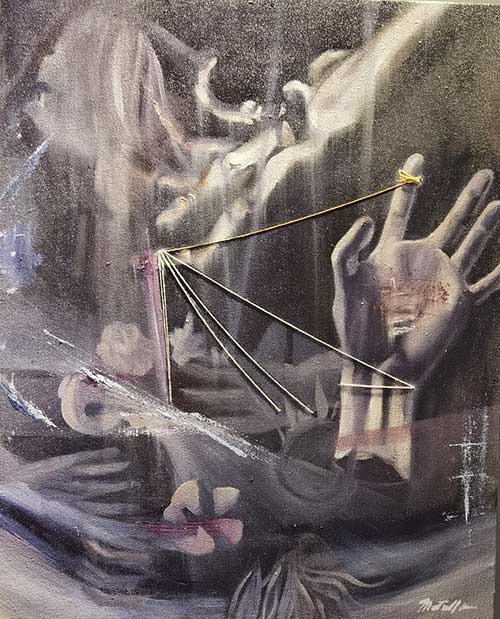

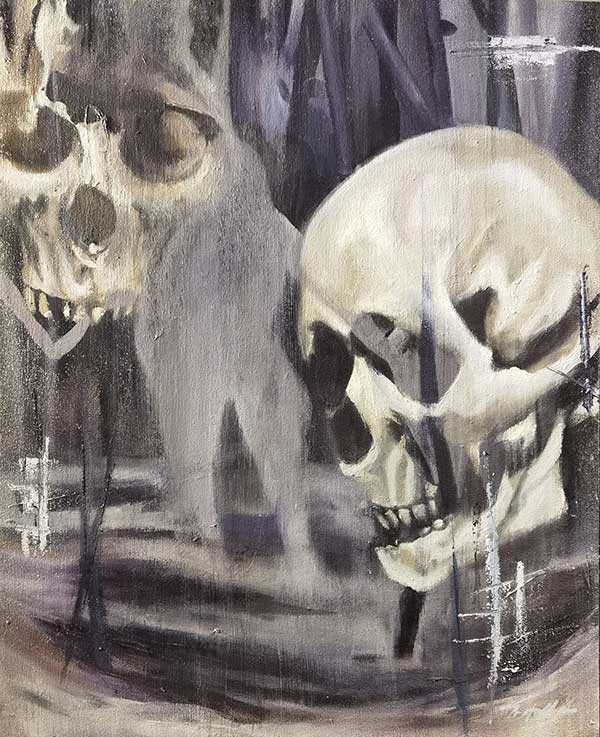

Tuvilla’s Mental Torment depicts two bowed skulls overlapping a human silhouette aptly represents psychological anguish’s kinship with death. Her work Getting Better shows a hand tied to a post – or is it a cross? It is reminiscent of scenes in horror movies when the hand of a supposedly dead person reaches out from the grave. Tuvilla’s figuration that lapses into abstraction is consistent with expressionism, especially the German kind, and aligns with her desire to depict her emotions and responses to events or circumstances in her life.

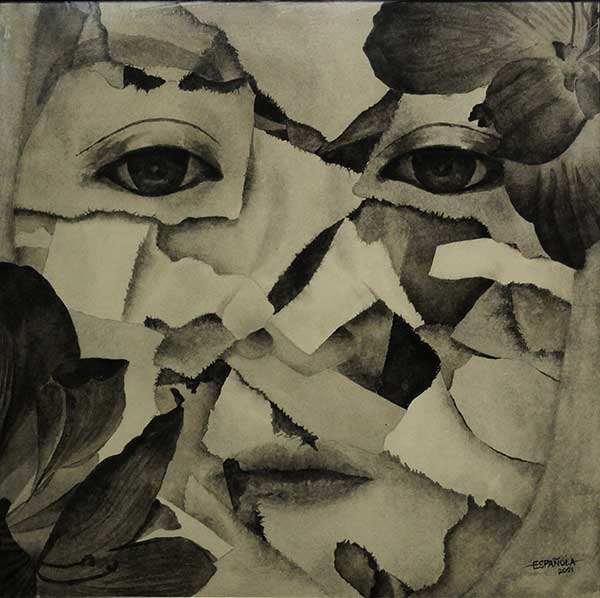

Española’s Torn No More is a portrait of a woman emerging from a heap of shredded paper – a testimony of slow or incremental reconstruction, restoration, and emergence. The same thing is articulated by her triptych My Truth Unfolds. However, the painting’s format suggests a self that is broken up that needs to be put into one whole composition or frame. These two works show Española as an adept communicator who carefully chooses her codes.

Marzz Capanang’s enlightenment is a blend of environmentalism and concern for humanity and the human spirit. The oneness of humans with the environment which the work intones is a shared view of most, if not all, indigenous cultures.

Itom nga Kalayo I and Itom nga Kalayo II are shaped canvases which can pass for a diptych as they are continuous or related compositions showing vast fields littered with what looks like pointed haystacks in the former and pyramids in the latter. The triangle, in symbology, represents higher perspective or enlightenment. In Capanang’s surreal landscapes that are akin to Chinese paintings in their economy and vitality as well as in their use of distance in the plane or level distance perspective, such potential for complex consciousness is under threat by the looming black smoke or cloud where a power characterized by an ill-omened eye resides.

Paul Furtado’s Rediscovery of Once was Deemed Insignificant is about the enlightened reprocessing of memories and experiences. This painting, in the mold of veristic surrealism shows a man navigating upstream in a landscape full of gigantic childhood toys. Furtado, in his artist statement, clarifies that the man in the boat is the owner of the toys. He deems the past (his, likely) as a life that had been lived like a child at play with nary a thought of dire consequences. Play-can-be-destructive is something that he proposes but not without hope of remediation. That the man in the boat calmly rows against the river’s flow amidst the incongruous scenery hints at some transcendent knowledge or force beyond human in him. This seems like Furtado’s conclusion: enlightenment or embracing some truth is liberating and enables one to navigate against the tides of the present and undaunted by the awfulness of the past that still haunts.

Enlightened as a thematic group exhibition succeeds because the artists delivered an enriched individuated engagement with the show’s concept despite the group-imposed artistic restraints and the constraints of space and venue.