The Philippines has over 3100 known caves. Featuring 12 chambers over its seven kilometer span, the Langun-Gobingob Cave in Samar is the king of them all. Discovered by Italian Guido Rossi in 1987, it was opened to the public in 1990.

We recently explored it to celebrate the Year of the Protected Areas or YOPA, which aims not just to convince people to conserve the country’s 246 protected areas, but to encourage them to visit the sites themselves.

Caves are underground chambers, usually situated in mountains, hills or cliffs. Generations of imaginative fear-mongers have made them the home of everything from treasure-hoarding dragons to a whip-wielding Balrog. In reality, caves are special ecosystems which need our protection, particularly from unscrupulous miners who would break apart tons of rock for a handful of precious stones.

Unique But Threatened Biodiversity

Samar Island, overshadowed by more popular places like Palawan and Boracay, isn’t usually considered a top tourist destination, owing to its long history as a hotbed for insurgencies and a punching bag for typhoons. Though the Philippines’ third largest island exudes rugged beauty, its real value as an ecotourism destination lies beneath the earth.

“Samar is unique because it is a karst landscape made primarily of limestone. Millions of years of weathering has created numerous caves and sinkholes on the island,” explains Anson Tagtag, head of the Caves, Wetlands and Other Ecosystems Division of the DENR. “Caves are special ecosystems which harbor highly-evolved fauna, most of which have adapted to darkness.”

Birds, bats, spiders, snakes, crickets and even blind cave fish thrive inside the Langun-Gobingob Cave. The lack of light confines plants to entrances, but mushrooms and other types of fungi cling to life as discreet denizens of the dark.

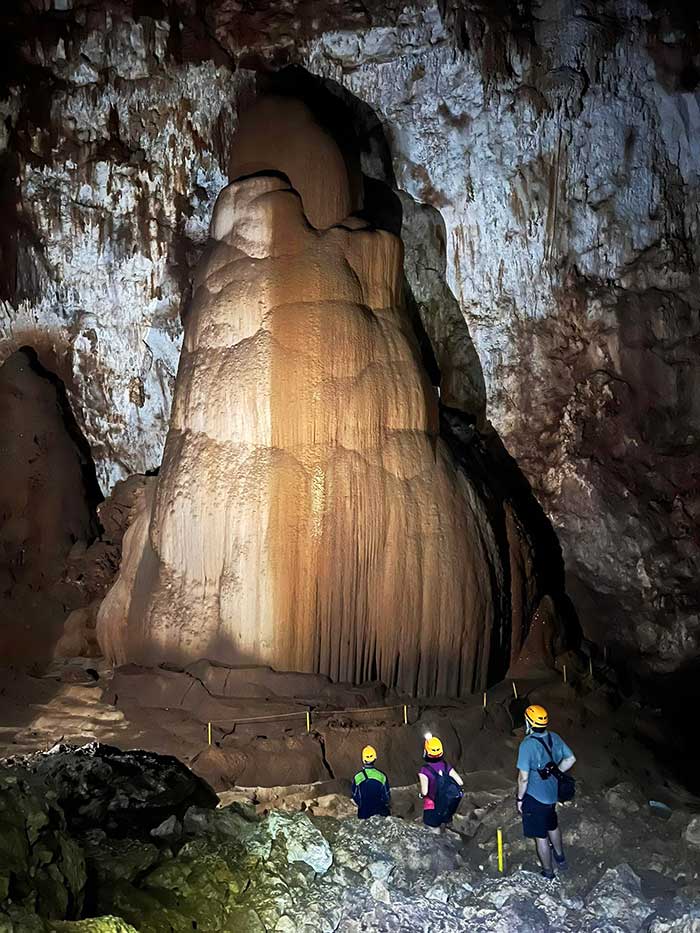

“The speleothems or rocks in caves are in a very real sense ‘alive’ – they just grow and move at timescales difficult for people to comprehend,” explains Dr. Allan Gil Fernando, a professor at the National Institute of Geological Sciences in UP Diliman. “The constant dripping of water for instance leaves minute traces of minerals like calcite. Over time these traces pile up to form hanging stalactites and their inverted kin, stalagmites. It takes about a century for a stalactite or stalagmite to grow one inch.”

It is because of their surreal beauty that many caves are sundered.

“People used to enter the Langun-Gobingob Cave to break apart and mine stalagmites plus white calcite rocks for collectors,” says Samar Island Natural Park (SINP) Assistant Superintendent Eires Mate. Our guide Alvin confirms this. “Locals used to mine the cave for Taiwanese businessmen, who paid a paltry PHP7 for a kilogram of rock. Balinsasayao or swiftlet nests were plucked out too, to be shipped to Chinese markets.”

The cave was finally declared a protected area in 1997. “Thank God for legal protection. Mining was effectively stopped,” says Eires. The Langun-Gobingob Cave is just one of many natural systems benefiting from the country’s protected area system.

“Declaring key biodiversity sites as protected areas is one of the best ways to ensure that future generations can continue enjoying their beauty,” says United Nations Development Programme Biodiversity Finance Initiative (UNDP-BIOFIN) Manager Anabelle Plantilla. “Visitors should positively support local communities but be mindful of the environmental impacts of their travels. They should for instance, avoid taking wild plants or leaving trash in tourist sites.”

Year of the Protected Areas

Launched in May of 2022, YOPA hopes to generate funds from tourists to ensure the continued management of protected areas hard-hit by COVID-19 budget cuts.

The Langun-Gobingob Cave is part of the Samar Island Natural Park (SINP), one of YOPA’s six highlighted parks, the others being the Bongsanglay Natural Park in Masbate, Apo Reef Natural Park in Occidental Mindoro, Balinsasayao Twin Lakes Natural Park in Negros Oriental, Mt. Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary in Davao Oriental, and Mt. Timpoong Hibok-Hibok Natural Monument in Camiguin.

The country’s caves are now open for tourism, but visitors should know what not to do inside them. “Cave tourism should be well managed and there are cave do’s and don’ts,” says Buddy Acenas from the GAIA Exploration Club, a Manila-based caving and exploration group. “A comprehensive assessment should be conducted before a cave is opened for tourism. Trained guides and set trails should be used to minimize human impacts. Like so many of our fragile wilderness areas, caves must be stewarded by those visiting them.”

For its part, the Philippine government is doing what it can to promote responsible tourism. “Our caves, mountains, beaches and other protected areas are now open for tourism. We invite both Filipinos and foreigners to come and visit, but to do so in an environmentally-responsible manner,” adds DENR-BMB Director Natividad Bernardino. “By practicing responsible and regenerative tourism in PAs, we’re helping our national parks flourish and recover from the economic blow they suffered from the COVID-19 pandemic.”