By Joseph Bernard A. Marzan

A renowned gastronomy scholar called on local government units (LGUs) to engage all food-related stakeholders in their jurisdictions, especially the grassroots levels such as public markets and carinderias, in conversations about local cuisine during the Filipino Food Month.

Guillermo “Ige” Ramos of the Ugnayan Center for Filipino Gastronomy said LGUs are key to this move because they were the ones who had better knowledge of the immediate community.

He cited the “Palengke Tourism Capacity Building Program” project with the Department of Tourism (DOT), which was started this year in Baguio City.

“We started the program of Ugnayan that, the grassroots level is included. I started with the public markets, because these are veritable cultural hubs. They are a cultural space, a very very active cultural space. They must be included in the discourse created by the Filipino Food Month,” Ramos said.

“With public markets as a social space, as a cultural space, and you also have carinderias here, which are becoming a part of our culture. People would think that when you would say Filipino Food Month, it would be just expensive restaurants and chefs,” he said.

Ramos agreed that tour packages should have a greater connection to food, particularly in Iloilo which is a Creative City of Gastronomy under the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

But he also emphasized that this should be done with a “culture lens”, warning against “exotifying” or changing the physical features of the establishments, the local industry stakeholders, and the food itself.

“Food has a lot of narratives. As a researcher, I use ethnographic tools to research and tell the story of how food gets made. In one place in Cavite, I have peg, usually where kakanin, lumpia, vegetables, and condiments would be sold. As is, where is, the sellers do not have make-up [or] costume. Whatever they are wearing, that’s it,” he said.

“We have to use a culture lens. What I teach students is that, what may be ugly and baduy for you the dignity of a person is being preserved by not putting makeup or costumes.”

The food scholar also openly expressed opposition to the idea of ‘One Town, One Product’, which is currently a program of the Department of Trade and Industry, saying that this and similar programs kills other products that may also be thriving in a community.

Ramos criticized the “One Town, One Product” program of the DTI for potentially stifling other thriving local products.

He cited Republic Act No. 8172 or the Act for Salt Iodization Nationwide (ASIN) Law, for the decline of the salt industry.

“For instance, when you have the salt beds, and then you have laws like the ASIN Law without any cultural impact study, it’s bound to kill the salt industry in the long run. In 20 years, we saw the decline of the salt industry, because it’s just [a] mitigating [measure],” he stated.

“Was hypothyroidism mitigated? If it was, then fine. But it killed asin tibuok, asin tultul, asin buyo, [and] the salt beds of Kawit [Cavite]. So what else will die? Although I’m a certified DOT trainer, they should be more open. Because not all provinces are equal. Some provinces are poorer than others.”

SOCIO-CULTURAL CONSTRUCTION

Ramos’ discussion delved into the heritage and socio-cultural construction of gastronomy, demonstrating how food, as an integral part of culture, also involves a complex web of social and economic factors.

He said that the culinary aspect of food is just one part of gastronomy, a convergence of four bigger factors, namely geography, ethnicity, community, and technology.

“Culinary is just part and parcel of gastronomy. You shouldn’t confuse culinary with gastronomy, because that always happens. Culinary is the art and science of cooking, while gastronomy is the art of food or choosing the right food, or studying the food according to the community, the environment, all aspects, including farming,” Ramos explained.

“Chefs and cooks are the last in the value chain. It starts with the geography. You have disruptors including climate change, natural disasters, and the unseen culinary traditions and practices,” he added.

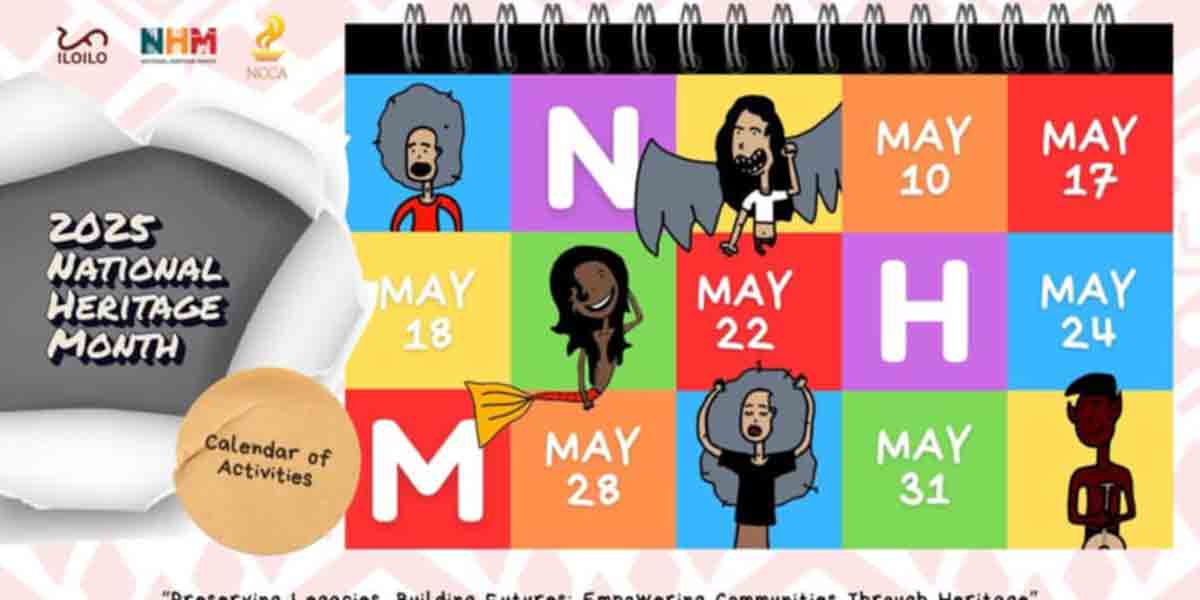

His talk was part of the kick-off of the Gastronomy and Sustainable Food Systems Conference, one of the highlights of this year’s local celebration of the National Filipino Food Month.

It is organized by the Iloilo City Government together with the DOT, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), and the Department of Agriculture.

Participating educational institutions include Western Institute of Technology, University of San Agustin, University of the Philippines Visayas, University of Iloilo PHINMA, Central Philippine University, Iloilo Science and Technology University, La Flamme Bleue Center for Culinary Arts, and the John B. Lacson Foundation Maritime University.

This is the city’s first celebration of the annual event as the UNESCO Creative City for Gastronomy.

Presidential Proclamation No. 469 issued by then-President Rodrigo Duterte in 2018 declared April as Filipino Food Month or Buwan ng Kalutong Filipino, aiming to ensure the appreciation, preservation, and transmission of Filipino culinary traditions as an established art form to future generations while celebrating and uniting regional diversity as a collective Filipino identity, and supporting the industries, farmers, and agriculture communities.

NCCA Special Projects Unit head Mark Omaña said that the Filipino Food Month aims to elevate food to more than “just a commodity that feeds empty stomachs.”

“[Food] is a culture, in viewing our identity. It is [a] collective effort of the fisherfolk, farmers, and local producers. […] It is an art form that celebrates and harmonizes diversity,” said Omaña.