By Elyssa Lopez

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Lea Alomia has started to strain her voice. At 47, the sari-sari store owner in Teresa town in Rizal province could not believe she could still be diagnosed with asthma. “When the doctor asked me: ‘Do you get exposed to cigarettes?’ I thought, no. No one is smoking at home.”

Alomia believes the heavy dust that came from an enormous cement plant near her home in Brgy. Prinza caused her asthma. Dust emitted from various processes in cement manufacturing is known to cause allergies and complications to the respiratory system.

Republic Cement, one of the country’s biggest cement companies, is the town’s major industry. It operates a 115-hectare plant in her town, spanning 2,326 basketball courts. “When the wind is so strong… you can really see white dust everywhere. Do you know that storm that happens in the desert? It’s like there’s a sandstorm here,” she said.

It is hard to be certain what caused Alomia’s asthma. Unknown to many residents, the plant is also burning plastic waste as alternative fuel for kilns that bake limestone into cement. Burning plastic also releases harmful emissions that could cause her condition.

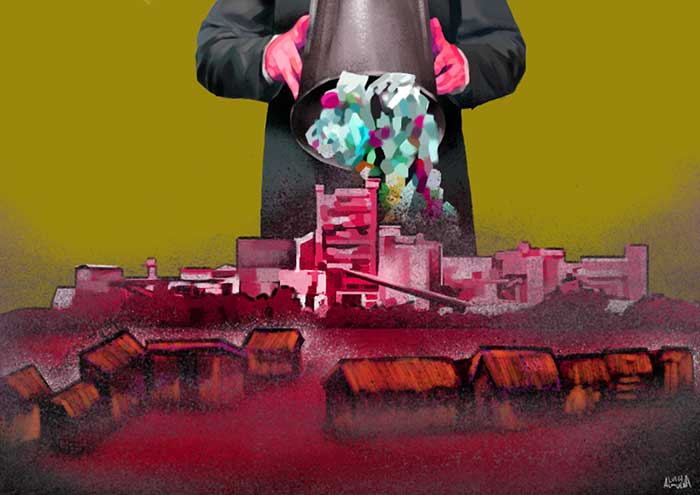

The kilns, which need extreme heat of up to 1,400 to 1,500 degrees Celsius, are mainly powered by coal. In a method called “co-processing,” more cement factories in the country have been using municipal waste as alternative fuel.

Refused-derived fuel (RDF), composed of flammable materials such as plastic and paper, is most commonly used. These are sorted and shredded into smaller sizes to fit the kilns.

It’s a method supported by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), which sees co-processing as a “sustainable” solution — and a better alternative to landfills — to address the country’s solid waste problem.

Environmentalists have long raised the health hazards of cement dust. They have raised concerns about RDF, too. A March 2022 report of the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) said a typical use of the alternative fuel “releases dioxins, lead, cadmium, mercury, and fine particles into the atmosphere.”

They have called for a temporary suspension of co-processing facilities, saying their impact on public health and environment should not be ignored.

They are wary that the Philippines may not be ready for wider use of co-processing because of the country’s outdated air quality standards and poor capability to monitor air quality.

And even if the standards are up to date, critics said co-processing is a “token scheme” for solid waste management that does not encourage reduction of plastic production in the country.

The manufacturers, they said, should be required to develop packaging materials that could be repurposed, which would be a better way to ensure that wastes did not end up in landfills or leaked into the environment by other means such as kilns.

DENR’s push

Republic Cement is among the country’s top cement makers that have marketed themselves as processors of municipal waste. The Teresa Plant, for example, can process 5,161 metric tons of waste a year, which is only equivalent to 0.1% of the solid waste collected (11,953 tons per day) from the National Capital Region in 2021, based on data from the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB).

Republic Cement has a pending application to increase the manufacturing capacity of the Teresa plant to almost three-fold its annual record of 1.7 million metric tons to 5 million metric tons. The company said the expansion’s general objective was for “energy and material recovery from waste resources,” and to provide “technically and environmentally sound waste disposal services.”

In a statement sent to the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ), Republic Cement said it did not receive any complaint regarding asthma cases in relation to its operations in Teresa.

The company also reported installing a “Bag House” system inside the plant in 2018, a device that collects and separates dust and particulates from the air.

“We are in close coordination with our LGU and Barangay Health Offices to respond to any health concerns that our community may have with respect to our operations. Once we receive such a complaint, it is immediately investigated from an operational side while simultaneously providing medical resources and support to the concerned community member,” Republic Cement said.

Ramil Paril, Brgy. Prinza’s environmental and health committee head, downplayed the health concerns. “You know, in our population of 8,000, maybe per 1,000 people, there are only one or two people who suffer from asthma,” he claimed. “No one has also formally filed a complaint about it [in our office].”

A 2010 DENR Administrative Order — AO 2010-06 — allowed wastes for burning in cement kilns. Last year, the DENR also amended the AO to expand the allowable wastes for burning to include “non-pathological healthcare wastes” like personal protective equipment (PPEs), face masks, and face shields.

Cement companies previously relied on imported RDF but EMB Director William Cuñado said he encouraged the cement companies in 2020 to buy RDF in the Philippines.

“I believe there will be a dramatic decrease in the waste to be dumped in [our] sanitary landfills [when co-processing plants start to use local RDFs] because we will use the garbage as a raw material,” he told PCIJ in an interview.

The pandemic saw a rapid increase in plastic waste in the country. “All industries are looking for cheaper raw materials, anyway. So if the garbage will be converted into raw material, there’s a big significant difference in the cost of fuel [for them],” he said.

But environmental lawyer and Ateneo de Manila School of Law professor Gregorio Bueta questioned the legal basis for the AO that allowed co-processing.

Co-processing is a form of incineration, Bueta said, which is prohibited under Republic Act 9749 or the Clean Air Act. The law aims to protect the country from the adverse effects of air pollution.

“The title of Section 20 of the law itself says: ban on incineration. Unless the law is changed, unless Sec. 20 of Clean Air Act is amended, industries which use incineration… [like] co-processing… run the risk of violating the law,” Bueta said.

Nine of the 29 cement plants in the Philippines already practice co-processing, according to EMB, as cement companies worldwide replace fossil fuels with alternative fuels such as RDF.

Three cement plants with co-processing activities are able to process 33,123 metric tons of waste per year, said Cuñado, citing industry data.

“If all cement plants [nationwide] engage in co-processing, we can have about 300,000 metric tons of garbage that can be used as raw materials,” he said.

Apart from Republic Cement, two other big cement companies in the country — Holcim Philippines and CEMEX Philippines — are also aggressively positioning themselves as processors of municipal waste.

As of 2021, the three companies have signed agreements with at least 46 local government units, and at least four fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) companies, to process their municipal and manufacturing wastes, respectively.

Many companies are still purchasing imported RDF but Cuñado said the EMB was in the process of crafting a policy to “encourage” cement companies to put up co-processing facilities in all of their plants. Most companies, he said, have “signified cooperation” if ever such a policy was formalized.

Strengthen monitoring

Environmentalists are wary the Philippines may not be ready for wider use of co-processing, despite its potential contributions to solid waste management, because of the country’s outdated air quality standards and poor capability to monitor air quality.

“As citizens, we are called to rely in good faith on the actions of our government, but from our experience, there’s a lot more to be desired in terms of implementation of laws,” Bueta said.

Emission standards prescribed under the Clean Air Act for stationary sources, which include cement kilns, for example, have been unchanged since implementing rules and regulations were promulgated in 2000. Under the law, the DENR was supposed to review the standards as needed, every two years.

“When the emission standards for [cement kilns] were made 20 years ago, RDF was not as widely used as it is now. There is really a need for further studies and analysis [on its use], and for redrafting of the regulations,” Bueta added.

Data from the Air Quality Management Section (AQMS) of the EMB showed that the annual average of particulate matter (PM) emissions of at least seven cement plants in the country ranged from 25 to 73 milligrams per normal cubic meter (mg/ncm) from 2018 to the first quarter of 2022. (The EMB did not disclose these cement plants or their locations. PCIJ also has no information on whether the data included emissions reporting from the Teresa Plant of Republic Cement.)

PM is a mixture of tiny solid and liquid particles in the air, which may include dust, dirt, soot, and smoke. It is one of the nine criteria air pollutants under the Clean Air Act, which means it has the capability to cause harm to the environment and public health.

While the PM emission average of the cement plants until 2020 was below the emission standards under the Clean Air Act, it was above the standards of Asian counterparts.

In India, where the cement industry is set to replace coal with RDF by 30% by 2030, PM emissions must not exceed 30 mg/ncm. Under the Philippines’s Clean Air Act, PM emissions may exceed 150 mg/ncm.

Republic Cement said the average monthly PM emissions of its Teresa Plant was below 14.5 mg/ncm in 2022.

According to the 2016 Global Burden of Disease study, PM affects more Filipinos than any other pollutant, when they are outdoors. Annually, 7% of all deaths in the country, or about 44,389, are due to ambient PM pollution, it said.

Stationary sources, which include cement kilns, are only one of the contributors to ambient air pollution. In the country, based on the latest data, almost 20% of emissions come from stationary sources. There is no data available on how much cement companies contributed to that number.

Specialists have also reiterated that emission standards varied per country as geographical features, population, and health risks differed. “But it’s still valuable to look at them (standards per country) because you can see how the Philippines is far behind,” Isabella Suarez, an analyst from independent think tank Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), said.

Major industries having the potential to emit 750 tons a year of any of the criteria air pollutants of the country are already required to install a continuous emissions monitoring system (CEMS), a facility that measures pollutant emissions. Out of the 29 cement plants in the country, 25 are required to have one, based on this standard.

But in an interview, EMB’s Cuñado said he was “not sure” if all cement plants in the country had installed the CEMS, or the date of their compliance.

PCIJ requested the CEMS reports of all cement companies in the country from the AQMS of the EMB from 2016 to 2021, but the office provided only annual averages of the emission reports of selected cement companies. AQMS initially agreed to an interview, but it was canceled.

In a 2021 landmark report on the economic and health repercussions of air pollution in the country, CREA noted that until recently, emissions monitoring on stationary sources was voluntary, and facilities reported their emissions to the DENR without a strict format.

Most stationary sources also self-reported. “This setup has likely resulted in selective reporting and even large errors in reported emissions data,” it said.

Aliño of Break Free from Plastic said the DENR’s record on policing cement plants was not reassuring. “When you look at DENR Administrative Order 2010-06, the guidelines on pollution monitoring [of the co-processing facilities] are limited… and then the compliance audit is just done once a year,” he said.

Even EMB Director Cuñado admitted that a study on the environmental effects of the emissions of local co-processing facilities had yet to be conducted more than a decade after the DENR administrative order was released.

He admitted the office needed to strengthen data collection capacities to better monitor industries’ compliance with emission standards.

Last year, the EMB released Memorandum Circular 2021-14, which mandated the establishment of an Air Quality Network Center. It followed DENR Administrative Order 2017-14 signed by the late Environment Secretary Gina Lopez, which was one of her last orders before she failed to get the nod of the congressional Commission on Appointments.

The orders seek the establishment of a central hub of all CEMS reports of industries required to have one and shift the submission of CEMS reports online. This way, the central office can immediately determine if a firm’s operations went beyond the emissions standards for specific pollutants.

CREA’s landmark study said such developments were a step in the right direction, but more work needed to be done.

The organization noted how the implementation of the air quality law should be supported by citizen empowerment. “The public should have the right to access environmental information in real-time, to participate in air quality governance, and to access justice where air quality laws are not implemented,” the study read.

EMB Memorandum Circular 2021-14 provides no guarantees the emissions reports will be accessible to the public.

Bueta had written about the use of imported RDF in the country for the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), a group of environmental organizations raising awareness on the need to eliminate pollutants.

“Prudence dictates that we look into the effects and impacts of using RDF in our co-processing facilities, whether imported or local. Given the unknown harmful effects to us humans, we are reminded by the precautionary principle, that even when there’s scientific uncertainty [to its effects] if there’s potentially irreversible harm, it’s better to stop,” he added.

Question of sustainability

Co-processing has economic benefits. A 2021 World Bank Study already found that the Philippine economy loses $780 million to $890 million a year due to the country’s failure to fully recycle plastics.

However, the same study cautioned that incentivizing the cement industry to replace traditional fuels with RDF without prioritizing “circularity interventions” — mandating product packaging to be apt for recycling, or adopting “reduce/reuse/new delivery models” — would have the effect of prioritizing a linear solution over more circular solutions.

The linear solution is how the existing production system looks like, wherein products are made then disposed of. The circular solution follows the concept of a circular economy, where waste is intentionally eliminated by designing products for reuse and recycling.

An earlier report by PCIJ revealed that co-processing was used for “plastic neutrality” efforts of at least four of the biggest FMCGs in the country. These partnerships were mostly made possible by the Plastic Credit Exchange, an organization that claims to help companies to be “plastic neutral.”

In a position paper published in January 2021, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) defined plastic neutrality as the “ability to completely offset a plastic footprint (whether an individual, company, organization, etc.) by directly investing in projects that collect or recycle plastic, or more indirectly by purchasing credits from a third-party organization that is tied to projects which collect from nature and/or drive additional recycling.”

The Plastic Credit Exchange facilitates this entire process, from the collection of plastic waste from local government units and informal collectors and their delivery to recyclers like co-processing firms. Republic Cement, CEMEX Philippines, and Holcim Philippines are all partners of the organization.

Some groups have cautioned against the use of the terms “plastic neutral” or “plastic neutrality” as they give manufacturers a justification for continued use of plastics.

“More precise and readily understandable terminology should be used to explain a company’s plastic impacts. Transparent monitoring and public reporting should serve as fundamental prerequisites to any communication on [plastic] crediting,” the WWF explained.

Some FMCG companies have said co-processing was only an “interim solution” to their plastic waste problem.

“Our partnerships with Cemex and Republic Cement for co-processing plastic waste provides a safe interim solution until a circular recycling alternative becomes available in the future,” said Ed Sunico, Unilever vice president for communication for Southeast Asia, in an email to PCIJ in October 2021.

But the EMB director has focused on consumers’ waste disposal practices and LGUs’ waste collection and segregation methods — not on FMCG makers’ plastic production practices.

“We have a lot of waste because we have a big population,” Cuñado contended during the PCIJ interview.

For certain groups, the entire waste problem needs a “whole-of-society” approach that starts with the government’s stricter enforcement of regulations, and with avoidance and reduction of waste.

Co-processing is not a sustainable solution, said IPEN in a report published in March 2022. It called for the development of viable solutions to the waste problem.

“If people are of the mindset that their waste will just easily be disposed of through modern engineering, or that mounds of garbage will suddenly disappear, then there is no motivation for them to change their lifestyle and consumption habits to reduce waste,” IPEN said in a report published in March 2022.