As summer temperatures rise in Iloilo City, so does the risk of food and waterborne diseases. The Iloilo City Health Office (CHO) recently intensified its campaign to prevent contamination-related illnesses, warning the public about the heightened dangers of bacteria and pathogens thriving in perishable foods and unsafe water. The initiative is timely—but troublingly familiar.

This is not the first time the city has scrambled to act as the thermometer climbs and illnesses spike. Year after year, the same cycle plays out: hot weather triggers warnings, illnesses prompt inspections, and then everything cools down—until the next crisis.

But this cycle hides a deeper, more uncomfortable truth: public health risks during extreme heat disproportionately affect the poor, and the systems meant to protect everyone are not built equitably.

When the CHO warned the public about how bacteria thrive in the heat and contaminate food and water, he was issuing more than a health advisory. He was exposing a long-standing problem: the urban poor have fewer options to stay safe, and their food and water sources are often the most vulnerable.

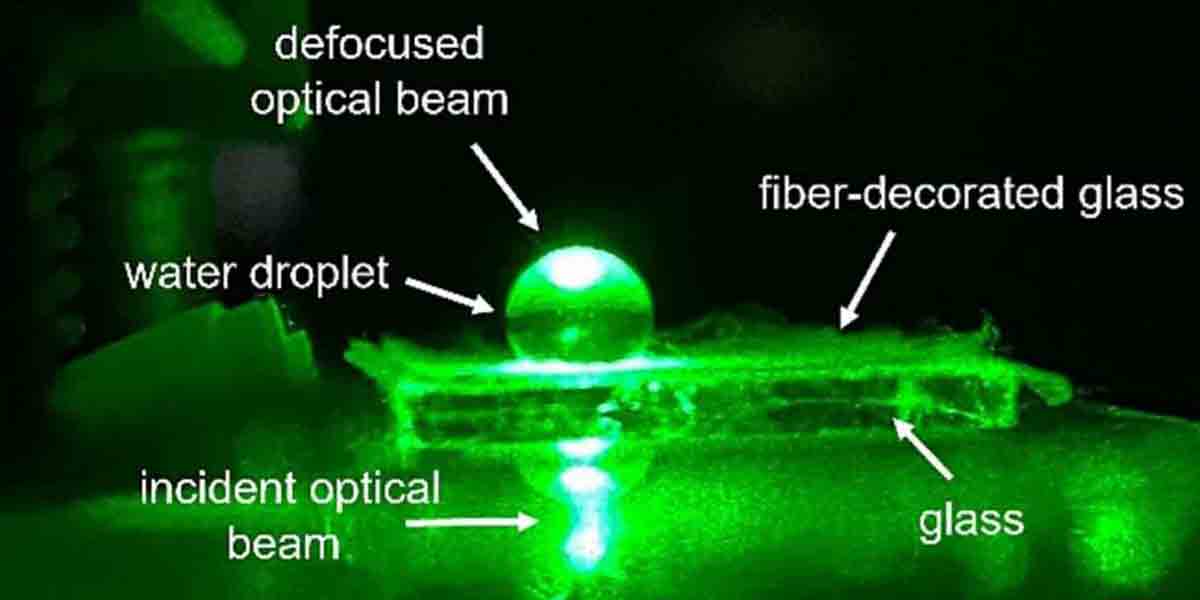

In many of Iloilo City’s informal settlements, access to clean and safe water remains inconsistent. While the CHO conducts monthly bacteriological tests on water refilling stations, what about those who rely on makeshift water sources, communal wells, or informal vendors? Some of these sources, especially in areas where condemned wells remain in use, are chronically unsafe.

The CHO has rightly stepped in by providing water tanks and emergency supplies in villages with no access to potable water. But these are temporary solutions to long-term neglect. Worse, poor communities are rarely informed of the results of water quality tests or given consistent education on water safety.

Then there’s the issue of food safety. In neighborhoods where families survive on daily wages, street food is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. It’s cheap, accessible, and often the only available option for working parents and schoolchildren. Yet it is also where food safety breaks down most often.

Ambulant vendors often lack refrigeration and are exposed to elements that promote spoilage. Ice used in drinks—especially during the summer palamig craze—is another danger point. The CHO has vowed to dispose of cold drinks made with ice blocks, but one must ask: Is this enforcement reaching every corner of the city, or only those visible to inspectors?

Fiesta season should be a celebration of abundance, but for many, it becomes a health risk. Households who can barely afford daily meals stretch themselves to hire catering services—many of which may lack proper sanitation permits.

The CHO’s call to verify if caterers are licensed is a sound advisory. But expecting individual households, particularly from low-income areas, to do this legwork puts the burden of public health on those least equipped to carry it.

Why not publish a public list of verified and regularly inspected caterers? Why not create a hotline or online platform to report suspicious practices in real time? Instead of treating fiesta season as a special case, the city can use it as an opportunity to teach long-term food safety habits.

The deeper problem behind these campaigns is not the intention but the timing. Why does the City Hall only intensify inspections and public information efforts when the heat index goes up?

Why aren’t food stalls, water sources, and catering services inspected with the same rigor in November or January? Why aren’t schools and barangays regularly engaged in food and water safety drills?

The problem with seasonal responses is that they send the message that danger only exists during the summer. But bacteria don’t watch the calendar, and contaminated water doesn’t care about weather reports.

The CHO’s monitoring of water refilling stations, its unannounced inspections of ambulant vendors, and its push for sanitation compliance are all commendable. What’s missing is the year-round, systemic commitment to safety that transcends weather alerts and press briefings.

The CHO cannot—and should not—be expected to fix the city’s inequality alone. But its current campaigns offer a critical opportunity for the city government to reimagine what food and water safety looks like in Iloilo City.

It must start with recognizing who is most at risk. The poor. The street vendors. The families dependent on informal caterers. The residents of barangays where clean water is a privilege, not a given.

City Hall must stop seeing food and water safety as seasonal concerns and start seeing them as infrastructure and governance issues tied to poverty, education, and public accountability.

It’s time to replace the band-aid with structural change. Let’s not wait for the next heat wave—or outbreak—to care about who gets clean water, safe food, and a fighting chance at health.

Because public health, like justice, must be for all—or it is for none.