By Dr. Clement C. Camposano

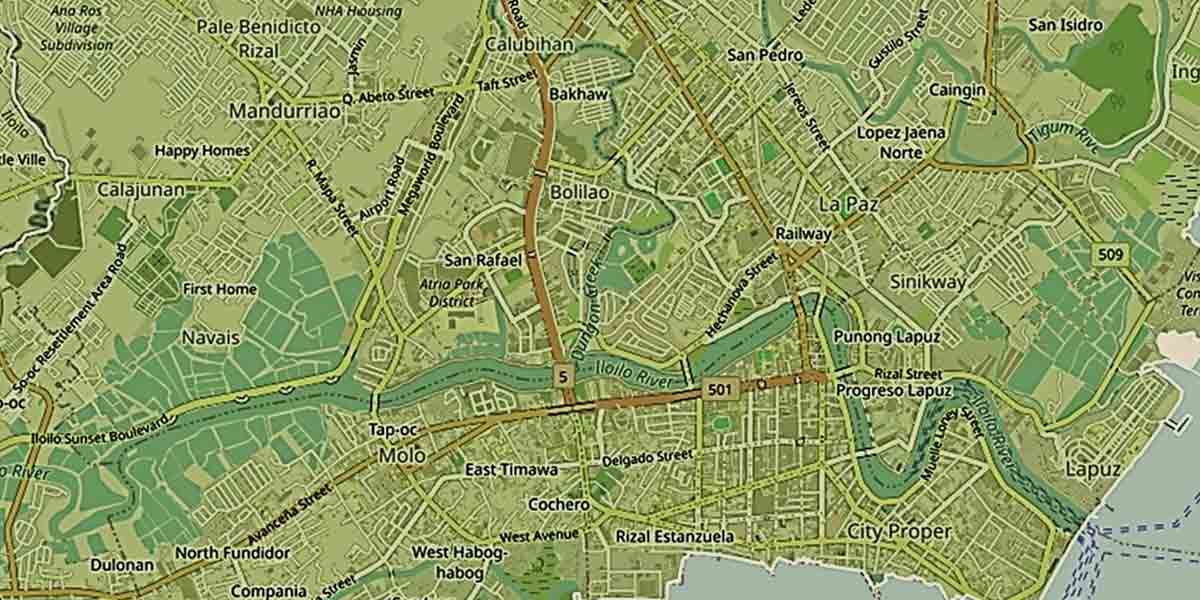

(Speech delivered during the 11th International Conference on Teacher Education in Iloilo City. Dr. Camposano is the chancellor of UP Visayas)

My warmest greetings to all of you participating in the 11th International Conference on Teacher Education organized by the U.P. College of Education. To our international participants, welcome to the Philippines and to Iloilo City. My congratulations to colleagues in the College of Education for putting this important conference together.

Given my own abiding interest in the subject, please allow me to be a little generous with my thoughts on the conference theme, “Preparing Teachers for Education 5.0, Toward Sustainable Futures”. Your conference hopes to examine how new technologies have resulted in changes in education, while underscoring the need for technology to serve the interests of teachers and learners. I wish to make two fundamental points in the hope that these will help frame some of the conversations that will happen in the course of this conference.

Firstly, we need to challenge the prevailing orthodoxy in the education community that all these advances in technology will somehow lead to improved forms of education (Selwyn 2010, 91). Our belief in technology — in what Schulte (2019) calls the “educational promises of the digital” — should be tempered by an understanding that while we are, as a species, distinguished by our use of technology, we are also “used” by technology.

Allow me to elaborate. Those who have explored the cultural consequences of the internet and its associated technologies have cautioned against “communicative instrumentalism or indeed… any other kind of instrumentalism” (Miller 2010, 9; see also Farnham and Churchill 2011; Boyd 2014; Kozinets 2015; and Caliandro 2017). These technologies, they say, should not be seen as mere tools for delivering curricular content. Attention must be paid to what Miller (2010) calls, “the surplus communicative economy” of technology use (9).

It is further argued “that technologies and human beings are co-determining, co-constructive agents. …With our ideas and actions, we choose technologies, we adapt them, and we shape them, just as technologies alter our practices, behaviours, lifestyles and ways of being” (24). Educators and educational institutions need to understand that they cannot have full control of the technologies that are used, nor of the consequences of such use (Kozinets 2015, 24).

Secondly, we cannot remain oblivious to the role that technology plays in the reproduction of inequality. As we continue to weave digital technology into our existing practices, we need to be reminded of the socio-technical nature of educational technology use. For instance, discussions of the educational role of the internet should never lose sight of what has been described as “the exclusionary potentials of networked learning” (Selwyn 2010, 94). These have to do with “basic abilities to self-include oneself into networks, [and] to subsequent abilities to benefit from these connections once they are established” (94).

Our belief in technology should come with the realization that students are differently positioned by personal histories and material conditions. A one-size-fits-all approach cannot work where there are significant differences in participatory resources, which are not only material but also cultural. We need to be empathetic, but we also need to be reflexive. It begins by accepting that teachers and administrators have class lenses, and the earlier these are recognized, acknowledged, and interrogated, the better for students.

Consequently, the promise of online and digitally enabled learning should not obscure the importance of ‘local’ contexts in the framing of learning processes and practices. Technology-based education is never context-free, and thus should not be abstracted from “local contexts such as the school, university, home and/or workplace and, it follows, the social interests, relationships and restrictions that are associated with them” (Selwyn 2010, 95).

In closing, I wish to affirm that we have good reason to think of technology as representing new possibilities for education. Yet, as digital technologies restructure the way we communicate by privileging certain features of human interaction, or radically alter the way information is accessed and consumed, there is a need for a more nuanced understanding of the role that these play in education. We certainly need to go beyond the instrumental issue of how effectively computer mediated communication might deliver content or achieve established learning objectives, or ensure learning continuity during periods of extreme disruption.

Teachers and administrators need to engage in critical sense-making by locating their work within fundamental questions about the purposes of education (Taguchi 2020, 636), even as they revisit their own beliefs and practices with respect to technology and its place in their work, and thus pave the way for re-imagining education in light of rapidly changing conditions. It is a tall order, but the work must be done.

Maayong aga sa inyo nga tanan! Good morning to all of you, and may you have fruitful days ahead.