By John Anthony S. Estolloso

TRUTH BE told, we did not survive them at all.

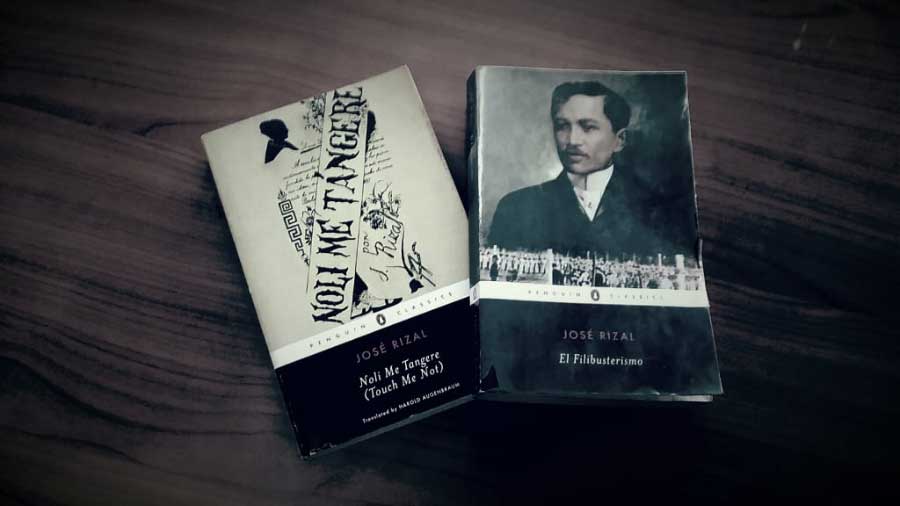

Our high school selves complied with all the requirements but as to how much we truly retained from Rizal’s novels left much to be desired. And for one who just recently read the novels in full, it came as a fresh surprise that so much of the books prove to be caustic irony and sharp commentary. Both novels were an entertaining critique, brimming with rather overly used tropes that would have been perfectly at home in a play of Moliere or Oscar Wilde. Oh, why did we not learn these in high school?

Historian Ambeth Ocampo, in his Rizal Without the Overcoat, pointed out that our schooling made us literate, but it never did teach us to love reading for its own sake – and past literary experiences with and the treatment of Rizal’s novels seem to corroborate this. Take Emilio Aguinaldo for instance, in his advocacy for the compulsory reading of the literature in the 1950s: when asked of some inspirational segments from the books, he admitted that he had in fact not read either!

In retrospect, the Noli is superb satire – it is comical at its worst and profound at its best. It is the best apologia in the canon of Filipino literature to prove that the critique was not only about the arrogant Spanish but of the idiot indio as well. (Doña Victorina, anyone?) Of course, we can always excuse the author for his ilustrado lens which takes the reader to dainty parties or on boating picnics where coarser characters are relegated as foils to the local glitterati.

That passages and characters seem to be projections from Rizal’s favorite novels is forgivable: after all, one can only write about the familiar and the comfortable – and why should Rizal’s literary idols find offense in this? For the artist of the pen, brush, or chisel, imitation is still the best form of flattery.

For instance, we see glimpses of Victor Hugo’s Fantine in Sisa’s madness, in almost the same way that the former insanely mourns her lost offspring. Cosette as the absent object of maternal affection is metamorphosed to Crispin and Basilio – and who can miss the similarity of how these youngsters were maltreated? Both Fantine and Sisa become delirious, seeing projections of their children in their mad yearning; both die in that state of insanity and never find redemption for their characters.

El Fili, as sequel, takes on a much darker and somber tone. Less is seen of the gaiety that dotted the first novel and Simoun, as a mature version of the naïve Ibarra, steps into the narrative’s limelight like a manipulative avenger from an epic penny dreadful. Put him alongside Dorian Gray or Abraham van Helsing, and one would hardly distinguish him from the serried ranks of these gothic characters. That the novel was dedicated to the three executed Filipino priests further heightens its macabre nuances.

Simoun dies as a tragic hero, finding some degree of redemption in a final confession to Padre Florentino. The deathbed conversation is poignant, to the point of being melodramatic. He reveals everything even as the distraught priest comforts him: is the scene not evocative of the worn-out Valjean from Les Misérables or the asthmatic Violetta from La Traviata as they make their exits?

Intriguing themes, intriguing tropes. So, what exactly stopped us from enjoying Rizal’s novels in high school?

Was it the staleness or the inadequacy with which our literature teachers handled the literature, leaving us with the aftertaste of digesting the stories with the same appetizing gusto as chewing dried cardboard? Was it the monotony of the cheap recalling of events and characters which never lent heart or soul to what Rizal wrote between the lines? Was it the passionless delivery of the chapter at hand?

If there is one encapsulating takeaway that we can get from this literary survival mode, it would be that nothing kills literary appreciation faster than a literature teacher who only regurgitates the basics of the narrative.

* * * * *

August is for the celebration of things nationalistic: national languages, history, Iloilo City’s charter day, Ninoy Aquino’s death anniversary, and our National Heroes Day. With this surfeit of nationalist sentiment inundating our academes, there is also this invitation and challenge to our literature teachers to revisit how we approach the study of our stories and narratives and perhaps, revamp these texts to make it speak more to younger audiences.

In conclusion, we ask: will future generations of students ‘survive’ Rizal’s novels? Of course, they will – academic compliance compels them to do so. But that is a shallow and insipid reason, and it might just be the final nail on the coffin of literary appreciation. Not unless our literature teachers do something about it.

(The author is the Subject Area Coordinator for Social Studies in one of the private schools of the city.)