By Martin Genodepa

After three years, Lubiok: Hiligaynon Art, an exhibit at one of the galleries at the Museum of Art and Cultural Heritage of the University of the Philippines in the Visayas has generated strong, adverse reactions from Antiqueño cultural workers, who have decried the title of the exhibit as another effort at “erasing” the Karay-a people, especially of Antique.

As Director of the UP Visayas Office of Initiatives in Culture and the Arts and curator of the exhibitions in the UPV Museum of Art and Cultural Heritage, I take full responsibility for whatever sins of commission or omission that viewers perceive in the different art and cultural heritage exhibitions of the museum.

However, it must be emphasized that art and curatorial projects and their statements are basically ideational propositions that are always contestable, depending on the viewer’s perspective and opinion. As propositions they are also dependent on existing trends of thought and ideas and may change with time. They are inherently meant to trigger reactions and provoke discussions.

The use of the word Hiligaynon to represent the art created by Ilonggos, Antiqueños, Akeanons, Capiznons, Guimarasnons, and Negrenses was never intended to “erase” a culture or people. Identities, like art, are constructions. For this exhibit, Hiligaynon is used, not to render the individual artists and their communities invisible and inconsequential. Hiligaynon is used, instead, in a cosmopolitan sense, as the exhibition framework. The artists are not just rooted in their province, but are also an integral part of their regional community.

The Hiligaynon language is generally understood, if not spoken, throughout the region because it evolved initially from the confluence of terms from Karay-a, Akeanon, and even Bisaya/Cebuano. Its lexicon continues to evolve and expand with the integration of concepts and vocabulary from other regions of the country and from abroad, propelled largely by continuous advancements and innovations in technology, travel, and communication. The development of the Hiligaynon language is not unique. All other languages in the region and throughout the world undergo the same processes of integration and assimilation to remain relevant and alive.

The use of the term Ilonggo to categorize the work done by artists in Western Visayas would likely touch more ethnocentric nerves because it could be deemed as more obliterative than the term Hiligaynon. The use of the term Binisaya, instead of Hiligaynon, has its own issues as well.

Hiligaynon Art in the exhibition title was intended to be celebratory because artists from Western Visayas have gained recognition and acclaim and have put themselves in the nation’s art map. However, the truth is, terms such Maranao art, T’Boli textile, Islamic art, Indian art, Egyptian art, or Greek art are accepted and used by art scholars and historians to refer to traditional art or aesthetics done by groups of people and nations adhering to common belief systems and canons that have resulted in shared creative and production techniques and styles, eventually yielding creative products with similar forms, shapes, colors, etc.

To insist that Karay-a art is unique and must always be differentiated from art created by artists from other localities and regions is but one of a number of schools of thought in the art world. Artist David Cortez Medalla, a Filipino and a pioneer of kinetic art once declared that in the modern and contemporary sense, there is only art done by Filipinos. Medalla’s declaration was a confirmation of the nature of modern or contemporary art: an amalgam of influences, a convergence of art psyches and worldviews and art techniques that are both equally native and universal.

In this vein, National Artist Jerry Elizalde Navarro was not doing Karay-a art or Filipino art. He made art as a Karay-a from Antique. He made art as a Filipino. A native of Western Visayas, he is halangdon; as a Karay-a from Antique he is harangdun!

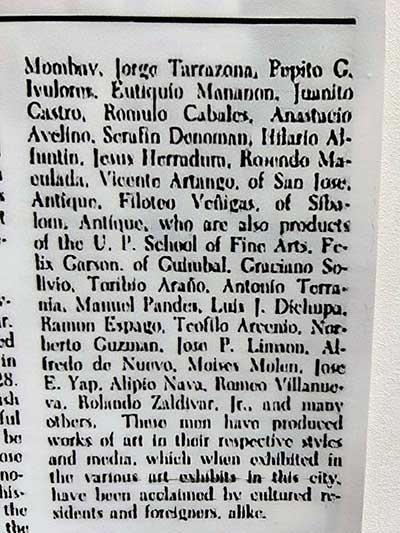

To dismiss the whole exhibition as a form of cultural erasure based on the perceived political incorrectness of the curatorial statement is not exactly a tenable stance – even political correctness may be anathema to the creative spirit. It must be noted that all the labels of the artworks in the exhibition explicitly indicate their creators’ places of birth or hometown and provinces–if and when research data is available–as proof that there is an even distribution of artistic talent in the region. The exhibition also displays the list of artists from all the provinces of Western Visayas, including those who, with the passage of time or a dearth of primary sources, may have been forgotten. It is hoped that future researchers, scholars, and art enthusiasts may be able to find more information and materials pertaining to these artists.

For instance, the family of Akeanon artist Telesforo Sugcang, who was a contemporary of Juan Luna, and who painted the ‘most unflattering portrait of Jose Rizal,’ according to Ambeth Ocampo, was elated to see their ancestor’s name in the list of artists in this exhibition. Sucgang, who was also a musician, later practiced his art in Iloilo, according to his granddaughter.

In addition, the exhibit presents a copy of a page of a publication that featured the Guild of Iloilo Artists, an artist organization older than the Art Association of the Philippines, which lasted until the 1970s. The Guild included members from Antique such as Vicente Artango and Filoteo Veñegas, who were products of the UP School of Fine Arts.

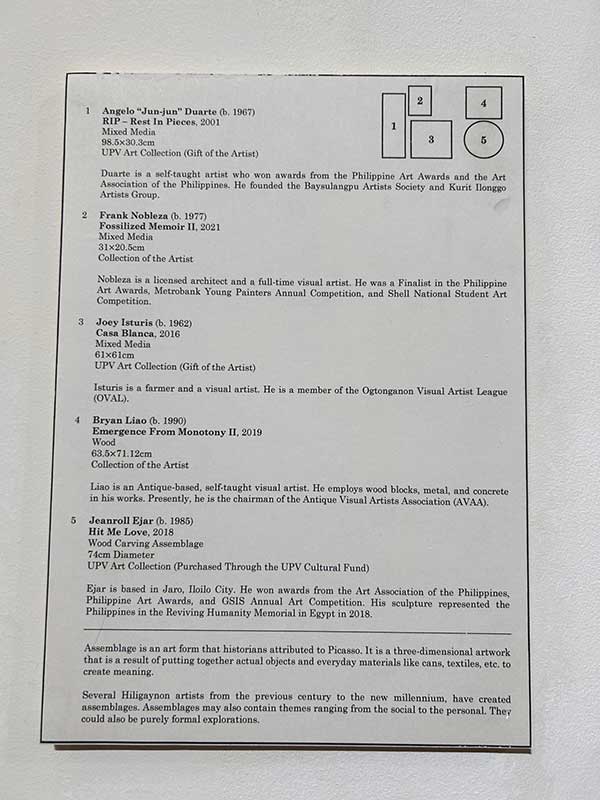

Hubon Madiaas, an Iloilo-based art organization founded in the early 1980s with the encouragement of now National Artist Jose Joya, included artists not only from Iloilo, but from other parts of the region. Hublag, an Ilonggo Arts Festival—probably the first contemporary art fair in the country—was organized by the Arts Council of Iloilo. Artists from Aklan and Negros participated in its short-lived existence from the late 1980s until the early 1990s. Now, there is Himbon Contemporary Ilonggo Artists Group, whose members are natives and residents of Capiz, Aklan, Guimaras, and Iloilo.

Were these artists subverting their identities when they participated in artist groups and art exhibitions that did not announce their individual ethnicity or hometowns?

Without the labels in Lubiok: Hiligaynon Art, it is hard to discern the nuances or distinction in the sample artworks of an artist who is an Ilonggo, Akeanon, Capiznon, Negrense or Antiqueño. If art is a universal language, the creations of this collective certainly speak to us in a variety of voices. Often, their voices are in harmony with ours, birthplace and culture notwithstanding.

Modern and contemporary art embrace a diversity of forms. Experimenting, breaking with the past, and searching for new expressions distinguish and differentiate the works and the artists in these periods. In the quest to transcend the traditional and the conventional, they branch out far from their roots. Origins and ethnicity are blurred. The dominant power and influence present this exhibition is not in its title. It is in the hands, hearts, and minds of the artists whose works mirror, find meaning, even mock, the times they live in.

That Antique/Karay-a cultural workers have raised the issue of recognizing ethnicity and cultural diversity in art is welcome. And while I credit the Karay-a cultural workers of Antique for asserting their recognition as a people, the Karay-a is not limited to Antique. On a personal level, their call for recognition has called my attention to my being a Karay-a from Guimbal. I, too, am Karay-a, who happens be from Iloilo, and fluent in both Kinaray-a and Hiligaynon.

When I create art, I am not conscious of my being a Karay-a because I am not concerned with making my work look Karay-a or Ilonggo. My proficiencies and flaws flow into my work, inflected by my being at once a Filipino, an Ilonggo, and Karay-a. Did I erase myself and my fellow Karay-a from Guimbal by having internalized the Ilonggo and the Filipino in me?

David Cortez Medalla, once opined that a bad artist, like a bad cook preoccupied with creating a particular taste, takes great effort in creating work that looks like it was made by someone from a particular ethnic group. A good artist, like a good cook who is mindful of the nutritive value of a dish, is concerned about how to make his work nourishing to the spirit.

In the greater scheme of things, will my being an Ilonggo from Guimbal, a Karay-a, matter in the bigger pond of regional art? Will my being from Western Visayas or Hiligaynon matter in the larger domain of Filipino art? And will my being from the Philippines matter in the vast history of world art?

On a more contemporary note, was Bette Midler erasing identities when she crooned:

“From a distance, we are instruments

Marching in a common band

Playing songs of hope

Playing songs of peace

They’re the songs of every man.”?

Although this is the only time I shall answer the tirades against the exhibit, this rejoinder is not meant to end the issue; rather, it is intended to stir the pot as it were, continuously, regularly, even endlessly with the aim of keeping the production of art of all forms in the region alive. Let the exhibition and its proposition continue to fuel the fire without malice and prejudice to those who will come after me to design an exhibition and make their own statements about the vibrant art of the region!

Editor’s Note: This is a rejoinder to the column of Roger B. Rueda headlined “The Hegemony of Hiligaynon: Erasing Karay-a Identity, One Exhibit at a Time” that was published in the February 19, 2025 edition of Daily Guardian