By Herman M. Lagon

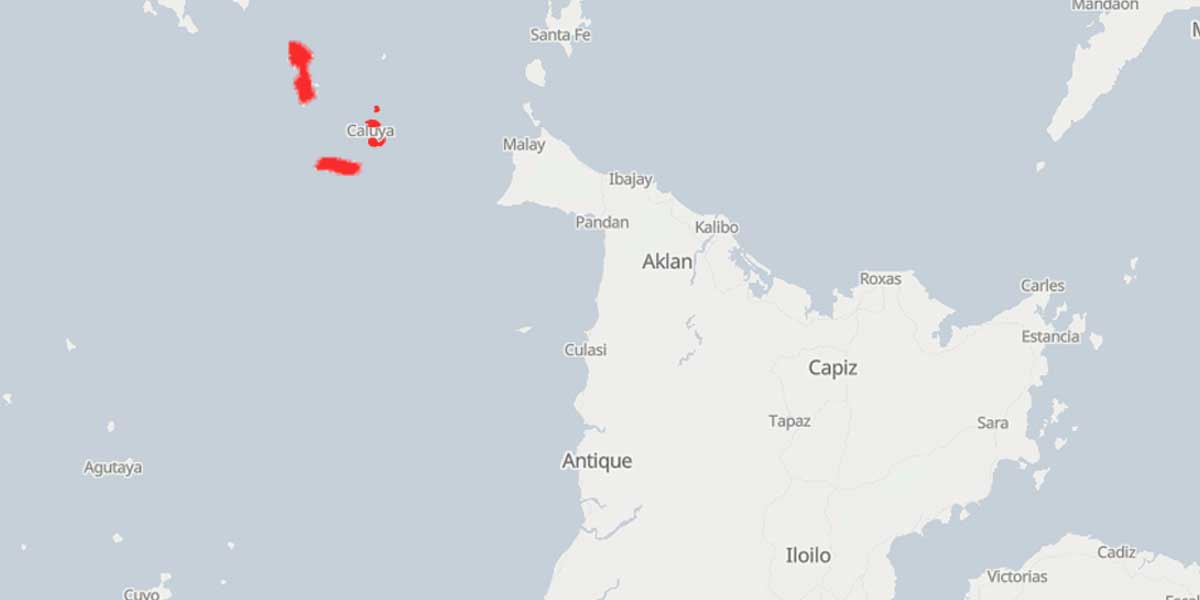

As I find myself halfway through a weeklong journey of cultural mapping training at INA Farm in Barotac Nuevo, the significance of our mission has never been more apparent. We are here, over a hundred strong, diving deep into the heart of Iloilo’s 4th and 5th districts, part of a larger initiative to map the cultural landscapes of Panay and Guimaras. This ambitious project, spearheaded by the NCCA, UPV, and various state universities and colleges, including ISUFST, is not just about pinning locations on a map; it is about charting the soul of our islands.

Cultural mapping, with its myriad facets, is a vital tool in our quest. The UNESCO-NCCA-designed “way of proceeding” allows us to pinpoint where our treasures lie, offering a visual feast that brings data to life. However, the engagement of local communities truly enriches this process. Their stories and knowledge ensure that the maps we create are not just accurate but imbued with the soul of our people. Every step is a discovery, from the inventory of cultural and natural assets to the analysis that reveals patterns and opportunities.

We are not just drawing maps; we are integrating these findings into urban and regional planning, ensuring that we do not leave our heritage behind as we move forward. Creating digital and more sustainable platforms means this wealth of information is not locked away but shared widely, sparking conversations and further study.

The importance of this work cannot be overstated. In a world racing towards the future, cultural mapping helps us preserve our past, ensuring that our intangible heritage and tangible assets are not lost but celebrated and protected. It is about community development, using our cultural riches to stimulate local economies and enhance pride and cohesion.

NCCA Commissioner Arvin Manuel Villalon’s words rang true during the fieldwork and workshop: “Our cultural heritage is key to understanding our identity and origins, crucial amidst globalization and rapid global changes.” He reminds us of an African proverb, “When an old man dies, a library burns to the ground,” highlighting the urgency of our mission. Getting inspiration from the commitment of Sen. Loren Legarda to this cultural endeavor, Commissioner Villalon stressed that cultural mapping is not just an academic exercise but a lifeline to the soul of our society, ensuring that the libraries within our elders and the landscapes that have cradled generations are preserved and cherished.

But cultural mapping is more than preservation. This is a launchpad for innovation and creativity. By identifying and fostering creative assets, we pave the way for new industries and opportunities, marrying the traditional with the new. And let us not forget the role of cultural mapping in environmental conservation, where the cultural significance of natural landscapes is recognized and safeguarded.

This initiative has drawn me into a world where every site and story is a thread in the vibrant web of our cultural heritage. Inspired by the commitment seen in the eyes of my fellow cultural mappers in the weeklong training, it is clear that the work we are prepared to thread is not just for us but for generations to come. We are mapping not just spaces but the human spirit, a variable that is given more depth through qualitative triangulation, ensuring that our cultural wealth is authentically recognized, celebrated, and preserved.

As we navigate through this process, guided by the wisdom of those like Commissioner Villalon, who reminds us that “Your most valuable assets and finest abilities are intangible and invisible,” it is clear that cultural mapping is a movement, not just a project. It is a collective journey towards treasuring the essence of who we are.

In the serene embrace of INA garden, among fellow cultural mappers from ISUFST, LGUs, and partner institutions, the gravity of our task is crystal clear. We are charged to document and ensure that the stories, traditions, and landmarks that define us are recognized and integrated into the fabric of our development. This is our mission, our responsibility, and our privilege. And if we do this right, regionwide, we hope that, with God’s grace, it will eventually be the start of a cultural mapping revolution in the rest of the islands in the country.

***

Doc H fondly describes himself as a ‘student of and for life’ who, like many others, aspires to a life-giving and why-driven world that is grounded in social justice and the pursuit of happiness. His views herewith do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions he is employed or connected with.