The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism obtained a copy of the Ombudsman’s proposals to amend the law requiring public officials to disclose their wealth, and sought comments from transparency advocates at the Right to Know Right Now coalition.

By Carmela Fonbuena

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Transparency advocates rejected many of Ombudsman Samuel Martires’s proposed amendments to the “SALN law,” based on a draft bill that his office had submitted to Congress and obtained by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Republic Act 6713 or the SALN law defines the obligations of public officials and employees in submitting their Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN), which has been used as a tool in fighting corruption in government.

PCIJ showed the proposed amendments of the Office of the Ombudsman to the lead convenors of the Right to Know Right Now (R2KRN), a coalition of transparency advocates, to solicit comments.

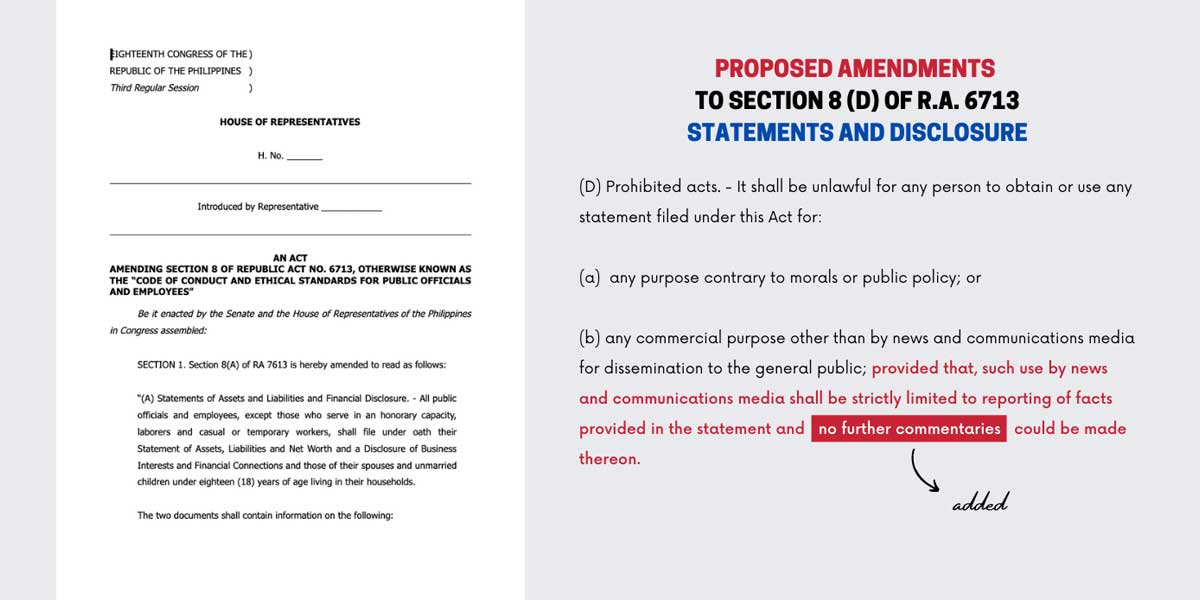

The biggest opposition was against the Ombudsman’s proposal to seek jail time for anyone who makes commentaries on the SALN. It was tantamount to censorship, said Jenina Joy Chavez of the Action for Economic Reforms, co-convenor of the R2KRN coalition.

Other proposed amendments were found to be “very vague.” They gave too much discretion to public officials and employees over which assets to declare or not in their annual statements, said lawyer Eirene Aguila of Angkop, also co-convenor of the coalition.

The draft was not the final version, according to Bayan Muna Rep. Carlos Zarate, who received a copy of the initial proposals. He said the Office of the Ombudsman committed to send him a final draft after undertaking further review and discussion of the amendments.

“We are studying this draft,” Zarate told PCIJ. “Certainly we will vigorously oppose any amendment that will restrict the right of our people to information, restrict freedom of expression and freedom of the press.”

‘No further commentaries’

Martires first advanced his proposal to restrict the media from commenting on SALNs during a House hearing on Sept. 9. He claimed the statements had been weaponized by the media in particular to destroy the reputation of individuals.

“Anyone who makes a comment on SALN of a particular government official or employee must likewise be liable for at least an imprisonment of not less than five years, no more no less,” he told lawmakers.

His proposal was widely criticized by the media, transparency advocates, and allies in government.

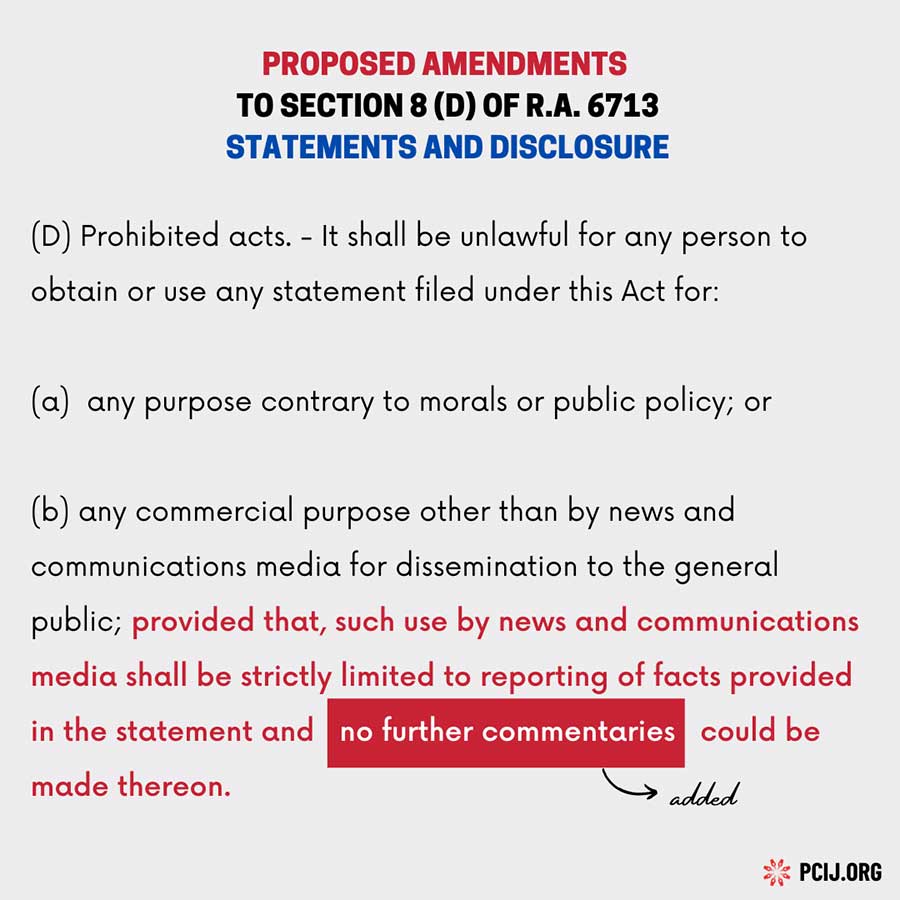

A copy of his draft bill, which was submitted within days after the hearing, showed that the amendment was added in the section on prohibited acts under RA 6713.

“Such use by news and communications media shall be strictly limited to reporting of facts provided in the statement and no further commentaries could be made thereon,” it said.

“That’s censorship,” said Chavez. “Once you release the information, it’s out there. People can read into it however they like.”

“That is obviously unconstitutional to begin with because it already borders on restricting your freedom of speech and freedom of expression,” said Aguila.

Section 4, Article III of the 1987 Constitution, or the Bill of Rights, states that “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

The particular provision should not have passed the technical working group, Aguila said.

Violations under Section 8 of the SALN law carry a punishment of imprisonment not exceeding five years or a fine of up to P5,000, or both.

Discretionary provisions

Chavez and Aguila raised more red flags on the proposed amendments that they said could provide public officials and employees with excuses to keep their wealth secret.

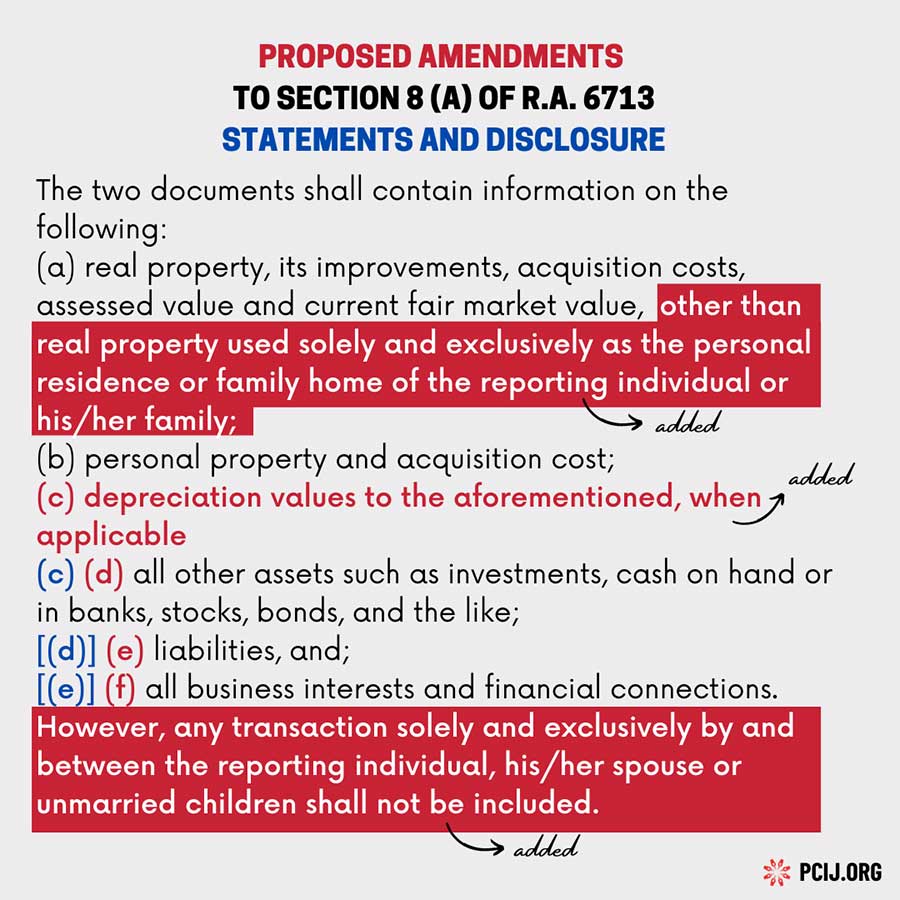

Aguila said one provision was too vague that it could be interpreted to mean that public officials need not declare real properties used “solely and exclusively” as personal residences or family homes.

Chavez warned that the amendment could be abused by public officials who own several residential properties to omit all of them in their declarations.

Aguila said it could be abused by dynasties in particular, citing the cases of the Cayetano and Ejercito political dynasties whose immediate family members had filed for candidacies in different districts using different addresses.

Aguila said privacy concerns might have been considered in proposing the amendment. But she said public officials could declare personal residences and family homes without providing specific addresses.

Information may also be redacted before it is released to the public, but the residences must be declared, she said.

Chavez and Aguila also rejected a proposal to omit the declaration of transactions between public officials and their immediate families, again for being “very vague.”

“A transaction could be: I am a mother and then I will transfer an entire grocery chain to my son. That’s a transaction. I own the power generating plant or the electric company in the town. I transfer shares of stock to my daughter. That’s a transaction,” she said.

It’s important to declare any transfer of control of assets within families to be transparent about public officials’ possible conflicts of interests, Aguila said.

Aguila said the SALNs are important tools in determining possible conflicts of interests, more than revealing the wealth of public officials. “You may not be stealing, but baka iba ang (you may have different) motivations mo [in seeking public office]. That to me is the bigger sin,” she said.

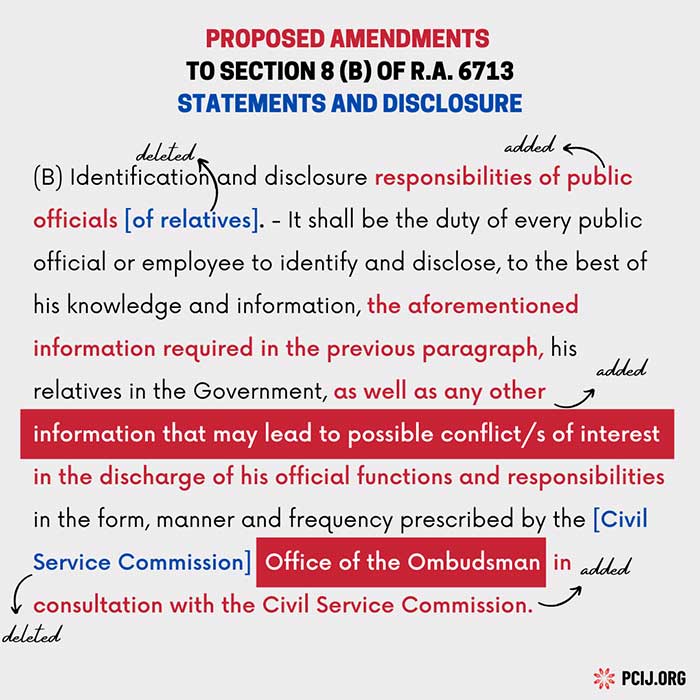

Chavez said it was also “curious” that the Office of the Ombudsman wanted to have the “first say” in the form, manner, and frequency that conflicts of interests would be disclosed.

It’s traditionally the Civil Service Commission (CSC) that prepares the form and manages the filing. “I’m thinking it’s better to leave that to the CSC, and the Ombudsman can really be a complaint body.”

Filing is supposed to be ministerial, she said. “If the Ombudsman is involved at that level, that changes a lot of things – not just for the filings of SALNs of the highest officials, but of all public officials and employees required to file SALNs.”

Release should be procedural

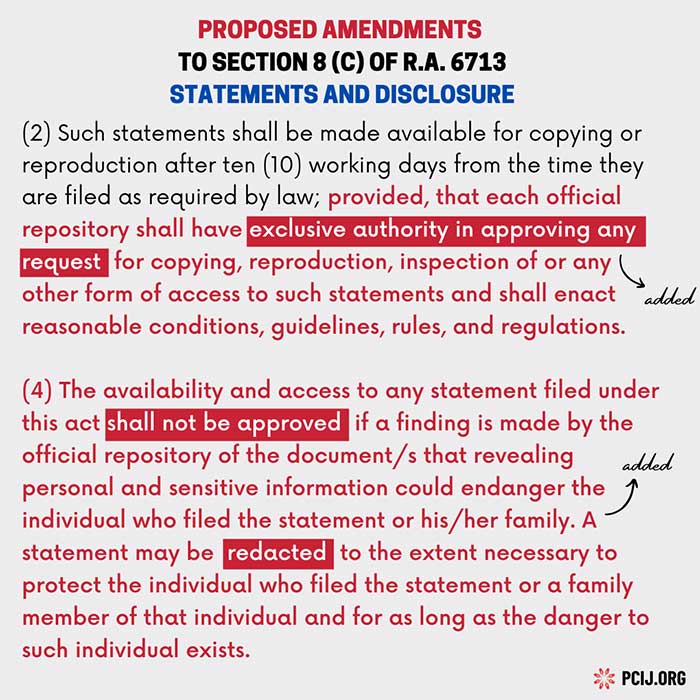

Chavez and Aguila also took issue with provisions that appeared to highlight the authority of custodians to approve requests for SALNs based on certain “conditions, guidelines, rules, and regulations.”

The way the amendment was phrased, custodians are again given too much discretion to deny requests for copies of SALNs, Chavez and Aguila said. It runs contrary to the spirit of the law, which is to give the public easy access to these documents.

Releases of SALNs should be procedural, they said. While there are legitimate exceptions, the bias should always be in favor of releasing the documents, they said.

The proposed basis for denial of requests –– endangerment of the public official or employee if sensitive information is released –– is also “too vague,” they said.

“Everything can put you in danger. You can say all your information can potentially endanger you. What about you does it endanger? It needs to be specific,” said Aguila.

“Privacy is important but it needs to be properly couched. You cannot use it as a blanket excuse,” she added.

Similar to specific addresses of family residences, sensitive information could be redacted, but the document should be released by default, they said.

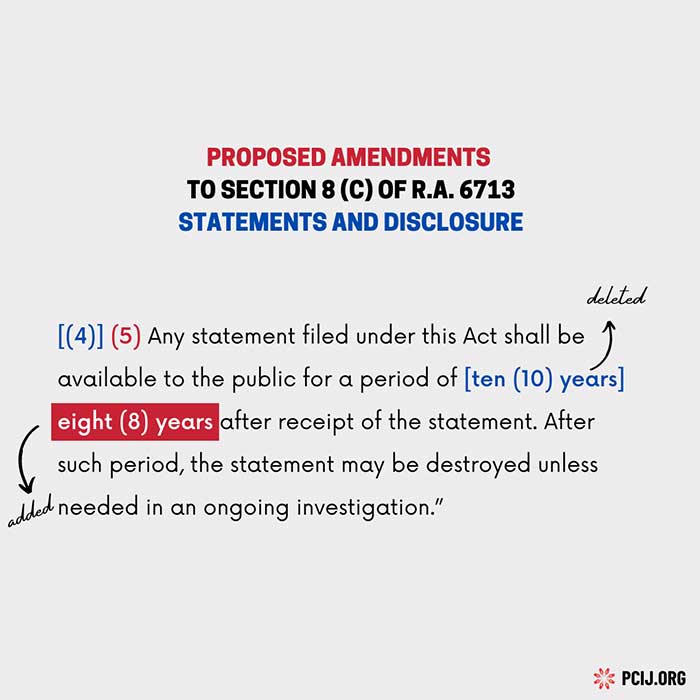

Chavez and Aguila also rejected an amendment to reduce the timeframe for when the documents would be destroyed, from 10 to eight years.

“It’s definitely a no-no,” said Chavez. “At this time and age nobody destroys records anymore.”

Aguila said the SALN information should be perpetually available.

Welcome provisions

Chavez and Aguila welcomed several other amendments however.

They both did not have issues with a proposal to transfer the custodianship of SALNs of the president, vice president, and officials of constitutional commissions from the Office of the Ombudsman to the Office of the Executive Secretary.

“This custodianship is good but it should not be used to work against me asking the declarant himself,” said Aguila, who wanted to highlight the responsibility of the declarants, or the public officials who filed the SALNs, to release their own statements.

“I’d like to remove the focus on who the custodian is,” she said.

Chavez also welcomed what she interpreted to be a proposal to form review committees within offices serving as custodians of SALNs.

Martires’s draft bill prevents anyone from filing complaints in relation to SALNs before the Office of the Ombudsman before such complaints are addressed by review committees.

Chavez said it needed to be clear, however, where the review committees would be created.

Push for consultations

Chavez and Aguila said widespread consultation should be conducted before any amendment is made to the SALN law.

The draft bill was likely not going to progress in the current 18th Congress, but Martires, who has a seven-year term as Ombudsman, will occupy the post until 2025.

Meanwhile, a memorandum that Martires issued in 2020 remains in effect. His office, the custodian of the SALN of presidents, has restricted public access to the wealth declarations of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Martires’ memorandum only allows requests from courts, government investigators, and from the declarants themselves.

Amid criticisms, the Office of the Ombudsman, during its budget hearing on Sept. 24, expressed it was open to revising the memorandum, but remained adamant that protections should be in place to prevent abuse.