By: Lucell Larawan

By: Lucell Larawan

Carabao dishes have not become a popular menu in most areas in the country because it is not as affordable as cow’s meat. Moreover, the animal helps the farmers. Only some parts of Bohol and Mindoro serve the meat.

For me, preserving the tradition of the Lobocanonbalbacua is important because as a sumptuous dish, it creates our sense of pride. Cultural leaders like Felipe De Leon aver that our sense of pride results to more self-confidence—the prerequisite to development.

My mother Linda and sister Myra do not cook balbacua; however, I have opened up to them my plan of sponsoring my sister’s balbacua store. The product can create a niche in the market composed of Tagbilaran residents.

How balbacua is done? The vesperas of the fiesta unfolds the drama. I see spices piling up in groups, in various colors and forms, like installation art in a gallery exhibit. There are bags of different sizes containing meats put together at the lower part of the abuhan. Papa Be usually cooks the dishes simultaneously. Balbacua is among them.

“This must be really tasty,” I said, expecting the luscious outcomes.

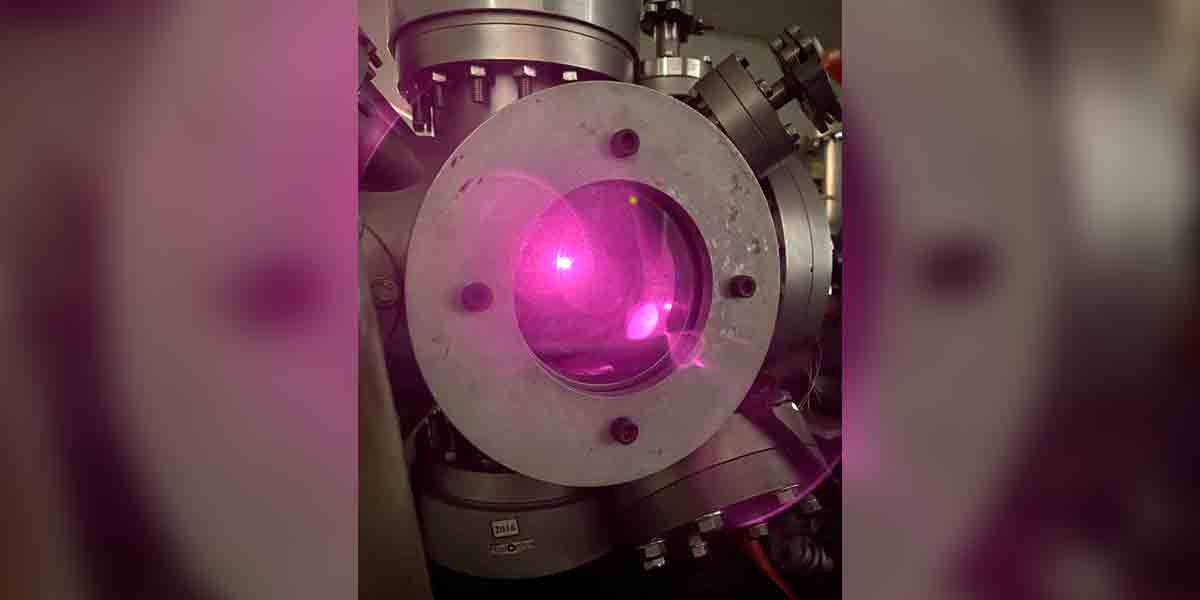

And what is done to the carabao legs? I see Papa Be burn some coconut charcoals using scratch papers set aflame with a match. As the charcoals get ready, he grills the legs until they look almost as black as the charcoal. The pleasant aroma fills the air.

The purpose of grilling first the legs, I suppose, is to accelerate the cooking. Carabao meat is relatively harder, so the grilling might shorten the process. More importantly, it also adds to the unique taste of the Boholano traditional way of cooking balbacua. This is how the Boholano balbacua stands out compared to its equivalent pata prepared by Ilonggos that only undergoes the boiling, not the grilling.

After grilling, I hear thudding sounds as a hammer hits the black-colored legs on a taparan. Scraping off the outer part using bolo follows. Hammering and scraping removes the burnt meat so no one eats the likes of charcoal. Papa Be then chops the legs cross-wise to around four or five inches. He puts them in a one-and-a-half feet wide cauldron for boiling with no spices yet. When it reaches the boiling point, the water is removed. It is then replaced with new water boiled to soften the meat for around four hours. This second boiling is done with salt, chili, onions, garlic and Ajinomoto.

If Papa Be had thought of operating a carenderia that specializes in balbacua, he could have sold out his dish. I could tell because of the yearning for more among the critics. I am not a food connoisseur but my view might be valid.

I see more affirmation of this fact during fiestas. The day starts around five in the morning in the kitchen. When Papa Be cannot raise a medium-sized pig to slaughter, he simply buys the meat through credit. “Tadtara sa ning tinai sa baboy, Doy,” he asks me on two occasions after he heated the entrails, exuding a tempting smell. Two of my father’s friends assist him. One chops spices, another cooks humba nga baboy, then they complete other tasks. My father cooks the carabao soup. All the sweats are compensated with the feedback of the day—the compliment of guests who expect the carabao soup menu and say, “Lami inyong balbacua. Lain nga pagluto.”

Around seven in the morning during fiesta, I hear greetings from Lobocanons. “Maayongbuntag,” quips a five-feet and five inches man wearing a white polo shirt. He says he hails from Camayaan in Loboc.

After a while, Papa Be asks the guests to sit around the long table which accommodates ten. I remember it serves two or three batches during breakfast. But the guest usually flock during the lunchtime where a barrage of relatives and friends from both parents come. Peals of laughter and light jokes would be heard often. Guests share their state-of-the-family reports.

The next day that follows ends the drama. Plates with blue floral graphic designs would go back to the wood and glass aparadors, along with spoons, forks and bowls. The thud of foot-steps cease to be heard in the wooden stairway with the usual greeting. Some dishes—including balbacua—stay in their cauldrons or Tupperwares. They become our food reserve for three or four days.

The festive atmosphere ends but the guests and I recall an encounter with Boholano—one to masticate into remembrance. The Japanese take pride in their ramen. The Chinese flaunt their Lanzhou beef noodles. Boholanos should start to promote balbacua.

Life is about savoring the moment, sages say. With Papa Be’s balbacua, a brief time is, indeed, a luscious memory.