By Herman M. Lagon

The Party-List System was meant to give the marginalized a voice in Congress. Still, it has become a shortcut for dynasties, business tycoons, and political insiders to tighten their grip on power. Instead of uplifting the underrepresented and the misrepresented, it now serves as an extension of influence for those who already have plenty.

Election watchdog Kontra Daya reports that over half of the 156 party-list groups in the 2025 elections do not truly represent marginalized sectors. Many are tied to political families, big businesses, or military and police figures. These groups are not grassroots advocates—they are well-funded players rebranding themselves as champions of the people.

A 2013 Supreme Court ruling removed the requirement for party-lists to represent marginalized sectors, paving the way for this exploitation. What was once a space for farmers, workers, teachers, and indigenous groups is now dominated by powerful names like the Romualdezes (Tingog Sinirangan), the Tulfos (ACT-CIS), and the Abalos clan (4Ps). According to Kontra Daya, business-backed groups like Ako Bicol and TGP have also turned the system into a tool for financial gain rather than public service.

ACT-CIS, for example, consistently tops the elections, largely due to the influence of Tulfos’s media. While it claims to advocate for crime prevention and public service, its dominance raises an uncomfortable question: Is it truly representing a marginalized sector, or is it simply another dynasty consolidating power? The same goes for Tingog Sinirangan, an extension of the Romualdez political machine. These groups are not dismantling barriers to representation—they, to many, are reinforcing them.

Then there is the creeping influence of big business. Ako Bicol, linked to the Sunwest Group, and TGP, backed by the Teravera Group, reportedly use party-list seats to protect corporate interests rather than uplift marginalized communities. Their presence in Congress is seemingly not about advocacy but maintaining power and influence. This blurred line between governance and business creates conflicts of interest that harm public welfare.

Beyond dynasties and corporations, some party-list groups lack transparency altogether. Many party-lists hide behind vague advocacies, leaving voters in the dark. Some nominees face corruption issues, while others have no real ties to the groups they claim to represent. Without stronger vetting mechanisms, party-list seats remain easy targets for exploitation.

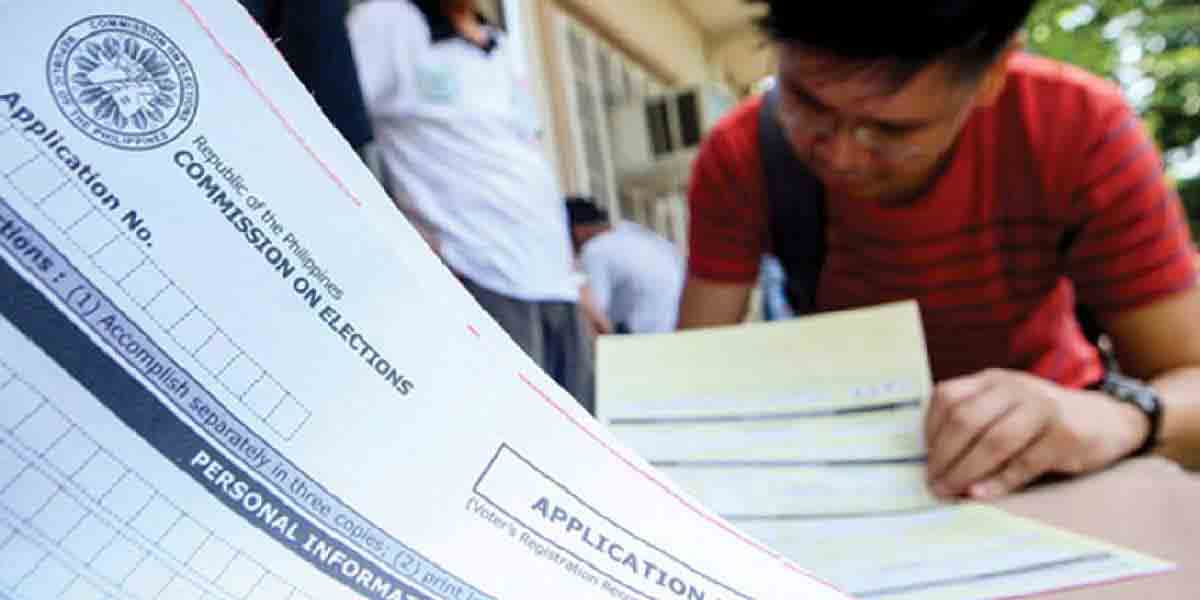

Despite its efforts, Comelec struggles to police these groups due to the absence of an anti-dynasty law covering the party-list system. With weak regulations, the system has become a free-for-all where influence, not advocacy, determines success. The burden of filtering out legitimate groups from opportunistic ones falls on the electorate.

Yet, despite the challenges, genuine advocacy-driven party lists persist. Groups (and their first nominees) like Akbayan (DLSU Dean Chel Diokno), Gabriela (Women Crusader Rep. Sarah Jane Elago), ACT Teachers (Educator Rep. Antonio Tinio), and Kabataan (UP Student Regent Renee Louise Co) continue pushing for legislation that benefits their respective sectors. They have actively participated in hearings and authored key laws on education, workers’ rights, and social inclusivity, proving that the system can still serve its original purpose—if voters learn from the past and choose wisely.

New voices are also emerging throughout the system. Mamamayang Liberal (Sen Leila de Lima), Bayan Muna (Human Rights Lawyer Rep. Neri Colmenares), and other progressive groups are stepping up against dynastic control. Based on their track record, these groups prioritize people over profit, representation over political convenience, and advocacy over access. Their system counterforce the misuse of the system.

For real change to happen, the legal framework governing party-list elections needs an overhaul. There must be stricter nominee qualifications, more explicit judicial definitions of marginalized sectors, and an enforceable anti-dynasty provision. Without these, the system will continue to be exploited, serving the few at the expense of the many. But expecting Congress—where dynasties thrive—to enact these reforms voluntarily is wishful thinking. This makes voter vigilance even more critical.

We must scrutinize party-list groups beyond their catchy slogans and media campaigns. An Ateneo School of Government study found that voters who actively research candidates make more discerning choices, leading to better legislative representation. However, accessing credible information remains challenging in a political landscape rife with disinformation. Election watchdogs, independent media, and civil society groups must step up efforts to provide voters with factual insights.

Every party-list vote matters. A vote for a political dynasty or business-backed group is a wasted opportunity to give real advocates a voice. On the other hand, a well-informed vote can bring meaningful change, pushing back against political opportunism. The stakes are high, and the consequences of neglecting this choice will be felt for years.

This election is not just about ticking a box but about shaping the leadership we want for the future. Our choices on May 12, 2025, will have lasting effects, and a party-list vote is more than just a name on a ballot. It stands for genuine representation, for leaders who serve the people, not their own interests. The choice is clear. It is time to return the party-list system to those it was meant to serve.

***

Doc H fondly describes himself as a “student of and for life” who, like many others, aspires to a life-giving and why-driven world grounded in social justice and the pursuit of happiness. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions he is employed or connected with.