By Karol Ilagan, Elyssa Lopez, Andrew Lehren, Anna Schecter and Rich Schapiro

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and NBC News.

Deck:

The transition to clean energy is pressuring mineral-rich countries like the Philippines and nickel mines like Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corp. to dig even more.

Body:

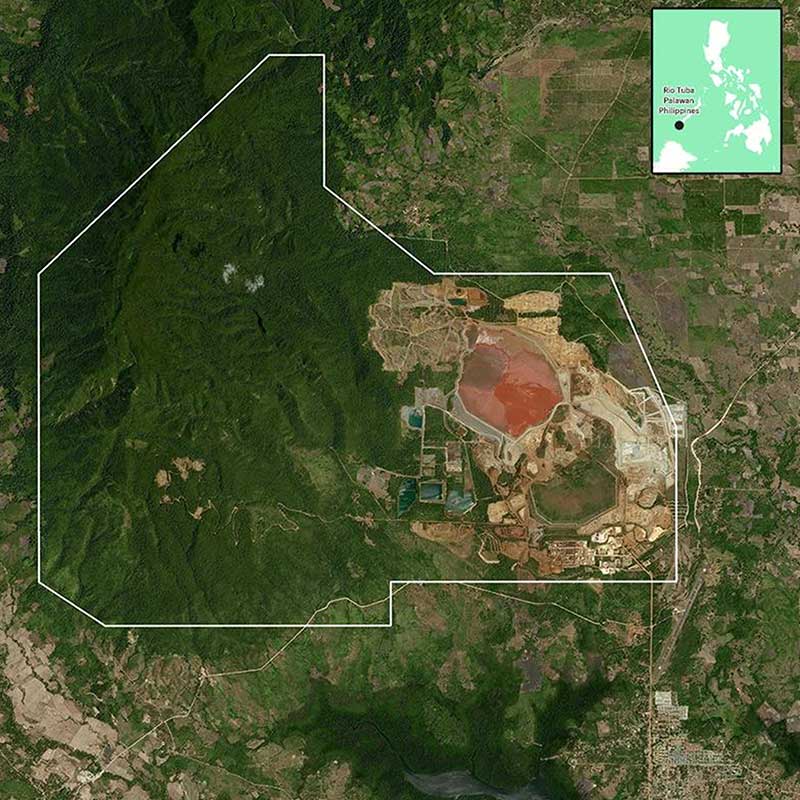

BATARAZA, Palawan – On Macadam Highway, mine trucks are king. Vehicles passing by this private road must yield or stop to make way for trucks carrying loads of sulphuric acid or nickel ore. Bakeries, carinderias, chaolong houses, hardware stores, money transfer agents and pawnshops skirt the seven-kilometer highway that connects the mine site to the pier stockyard by the Rio Tuba Bay. Red dust paves the road and blankets the mining town.

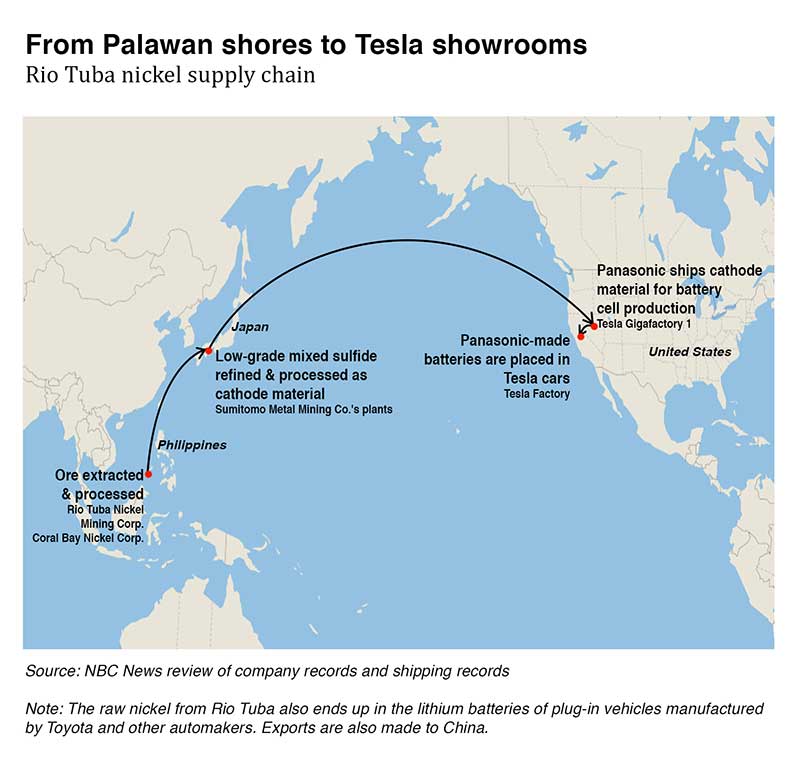

Built by Coral Bay Nickel Corp. (CBNC), a processing plant, Macadam Highway is Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corp.’s physical link to the global supply chain. Trucks plying this route transport the ore extracted by Rio Tuba and processed by CBNC for export to Japan.

NBC News, PCIJ’s reporting partner, reviewed corporate reports from the Japanese mining giant Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd. and found that the processed nickel goes through refineries in Japan, where it is converted into nickel cobalt aluminum oxide cathode material for Panasonic’s lithium ion batteries. (See infographic.)

Sumitomo Metal Mining holds roughly a 25 percent stake in the company that owns the Rio Tuba mine, Nickel Asia Corp., which is based in the Philippines.

In 2019, the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) gave conditional approval to Rio Tuba’s application to renew and amend its Mineral Processing Sharing Agreement (MPSA). With two of four requirements accepted as of writing, the mining firm is on the verge of a major expansion in Mt. Bulanjao, most of which had originally been designated as “core zones” or areas of maximum protection by law.

As superpowers pledge dramatic drops in their economies’ carbon emissions, the clamor to adopt renewable energy (RE) technologies is pressuring mineral-rich countries like the Philippines and nickel mines like Rio Tuba to dig even more.

While carbon emissions need to be kept to a minimum to address climate change, experts are wary that the transition to renewable energy technologies will encourage the environmentally destructive industry.

The country has the second-largest nickel reserves in the world. Since Indonesia banned ore exports in January 2020, the demand for Philippine nickel and its price increased. Rates are also expected to go up even more as the nickel requirement for clean energy systems is anticipated to rise fourfold by 2025.

With Covid-19 battering most of the world’s economies, the Philippine government, after leading a crackdown on erring mining firms, has turned to the mining industry to boost revenue and create jobs. In April 2021, President Rodrigo Duterte, once a mining critic, lifted a nine-year moratorium on new mining deals.

Industry experts expect new nickel mining sites to open in the coming year. Government data as of 2021 showed that three nickel companies had submitted exploration permit applications since 2019. If approved, this would bring the total number of nickel mining projects in the country to 34.

The Philippine Nickel Industry Association, a lobby group, is also developing a roadmap to identify downstream markets for nickel mining companies such as local processing and preparation of raw materials for batteries. At the moment, only two mines in the Philippines, those of Nickel Asia’s, are processing extracts.

Nickel demand on the rise

According to a 2021 International Energy Agency (IEA) study, energy transition is going to drive a huge demand for minerals and metals. In a scenario that meets the Paris Agreement goals, the agency estimates that the share of clean energy technologies to total demand will rise to over 40% for copper and rare-earth elements, 60% to 70% for nickel and cobalt, and almost 90% for lithium over the next two decades.

While copper has long been used in the manufacture of gadgets and materials for infrastructure projects, lithium and nickel are becoming synonymous with the RE boom as they become in-demand for the electric vehicle industry.

Electric vehicles are powered by rechargeable lithium ion batteries. These batteries have varieties, but the most popular in the industry are the lithium, nickel, cobalt, aluminum oxide (NCA) and lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC), as they can hold a larger amount of energy over other varieties. According to the Nickel Institute, current versions of the NCA and NMC lithium batteries are composed of 80% and 33% nickel, respectively.

Because nickel can store high amounts of energy, it’s part of solar power systems, which use mirrors to direct sunlight into a transmitter that can generate electricity. Some wind turbines also use nickel as protection from fluctuations in temperature.

Global consulting firm S&P Global Market Intelligence forecast demand for nickel from the battery sector to increase fourfold between 2020 and 2025, as the sector’s share in the global demand for the metal to reach 15.7 percent by 2025.

Philippine mined nickel production is expected to increase further to 550,000 tons, from 2021 to 2025. “[This is] based on expectations that Indonesia’s ban on nickel ore exports will continue to encourage Philippine producers to raise output,” said Jason Sappor, an S&P Global Market Intelligence research analyst.

The cost of clean energy

But not everyone takes these developments as good news. The renewable energy push of much of the Western world, while helping win the battle against climate change, may mean more environmental worries for the Philippines.

Environmental activists argue that the transition to clean energy led by the push to produce batteries for electric vehicles, solar panels and other renewable storage is unleashing unprecedented levels of mineral extraction and “transition” metals. This is bad, according to them, because of the environmental destruction and human rights abuses associated with mining.

A paper by War on Want, an environmental advocacy group, illustrates how these problems could worsen, citing cases in the Philippines, Indonesia, New Caledonia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“Each new green technology,” the report said, “has a potential for extractivist violence and worker exploitation.”

Even the IEA study notes that mining can result in the displacement of communities, loss of endangered species’ habitats, water contamination, air pollution and even noise pollution. The report does highlight that it may be possible to manage these impacts by integrating environmental concerns at the early stages of project planning.

But it also emphasizes the far-ranging repercussions of the impacts of mining: “In sensitive areas, such as habitats of endemic species or traditional indigenous territories, engaging in new mining developments might present a lower societal value than maintaining healthy ecosystems.”

Palawan and the entire Philippines fit the description.

‘Digging to disaster’

It’s lamentable when corporations fail to observe the principles of fairness and justice, said environmental lawyer Grizelda Mayo-Anda. Indigenous peoples and farmers in Bataraza, she said, would probably not be able to buy Tesla cars, but they and the future generation would bear the brunt of the impacts.

“It is grossly unfair,” Mayo-Anda said. “It is an inter-generational equity issue for the future farmer’s children and indigenous people’s children and their children’s children. It’s an issue of justice.”

The idea of fairness is not lost on farmer Jeminda Bartolome who lives in Taratak, one of the barangays that would be affected should Rio Tuba’s expansion on Mt. Bulanjao proceed. Describing mining as “salot” or plague, she says the impending expansion would mean hunger and illness.

“Sila, umisip sila ng kagandahan ng kalusugan nila, pero iniisip ba nila ang kalusugan namin dito (They think about themselves, but have they thought about our health here)?” Bartolome asks. “Ano’ng gagawing paraan namin? Kung masiraan ang kabuhayan namin. Kung matibagan kami ng bundok. Dapat pantay (What are we going to do? If our livelihood is destroyed. If our mountain is flattened. It should be fair).”

William Holden, a geology professor at the University of Calgary consulted by then Environment Secretary Gina Lopez in 2017, said mining sites in developed countries like Canada do not have communities nearby. Storms and floods do not really happen there.

“The problem with mining in developing countries is the environmental impacts of it. It degrades the environment that people rely upon for subsistence and livelihoods. We see it in Peru… we see it in the Philippines,” said Holden.

In 2012, Holden published the book “Mining and Natural Hazard Vulnerability in the Philippines,” which extensively documented the tragedies and accidents caused by the mining industry in the country. In one chapter, the professor listed how typhoons from 1911 to the 2000s had repeatedly caused flooding in several mining sites in the Philippines. The incidents led to the contamination of bodies of water with hazardous elements coming from the mining sites. And then there are accidents solely caused by human error, like the Marcopper spill in Marinduque in 1996.

Holden’s book concluded that mining was not fit for the Philippines because of its susceptibility to earthquakes and torrential floods, as well as poor economic benefits gained from the industry.

“Given mining’s environmental effects and the hazards present in the Philippines, a development paradigm based upon large-scale mining is an example of digging to disaster, not an example of digging to development,” said Holden.

Shigeru Tanaka, director of Tokyo-based Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC), explained why it’s difficult to do “responsible mining” in countries like the Philippines and Indonesia. The type of nickel in these countries is found just below vegetation and a thin topsoil, he noted.

“[Y]ou can’t dig under. You can only dig horizontally so if you want more nickel, that means you have to destroy all the vegetation,” he said. “And if you want to dig fast, because the supply demand is so high, then your reforestation speed cannot catch up with the deforestation.”

Tanaka is also a member of the Ethical Keitai Campaign, a Japanese consortium of NGOs that examines supply chain due diligence trends of Japanese electronics companies.

It doesn’t help that most of the country’s nickel is exported directly to China, which has loose regulations on the environmental compliance of mining companies. In 2016, the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals and Chemicals Importers and Exporters (CCCMC) formed the Responsible Cobalt Initiative (RCI) in a bid to address child labor concerns of cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

However, in 2017, Amnesty International reported that the Chinese business chamber had been slow in tackling concerns not just on child labor, but on other potential human rights violations of other member companies.

While Western companies have pledged to practice responsible sourcing of minerals, the same might not be expected from Chinese companies. Even companies in the rest of Southeast Asia have been silent in talks on carbon neutrality despite the region’s susceptibility to the climate crisis.

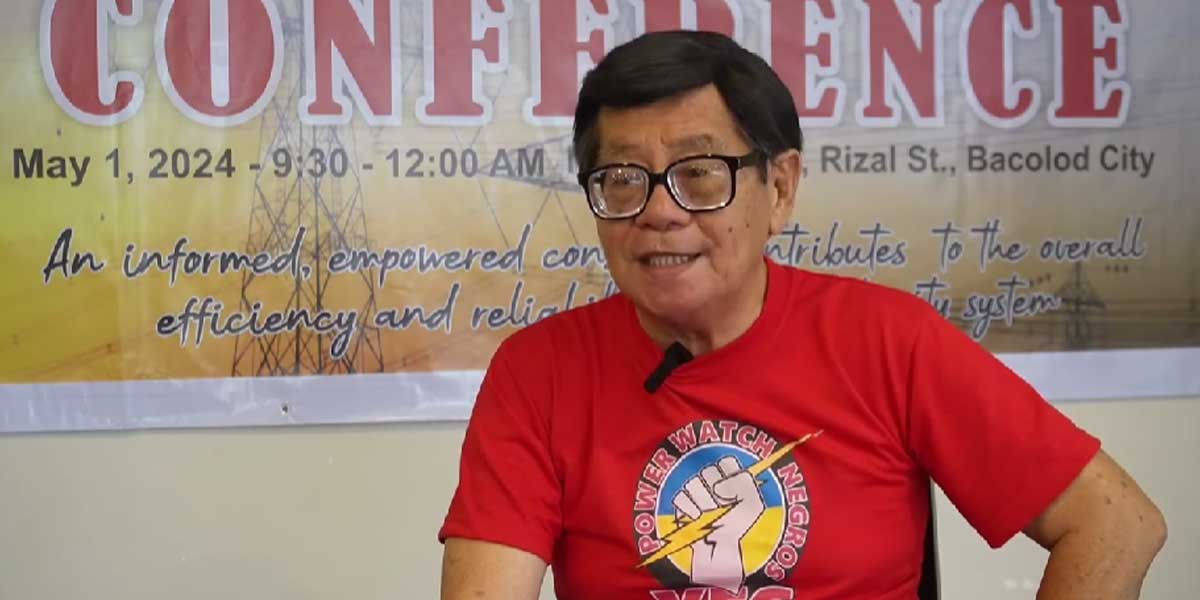

“Pressure from the end-receiver of our minerals can certainly help… (But) international pressure to heighten the standards for mine performance is absent here (in the Philippines). And without that, there is no pressure to raise standards,” said Jaybee Garganera, national coordinator of Alyansa Tigil Mina (ATM), an anti-mining group.

Representatives from Tesla and Toyota did not respond to NBC News’ requests for comment. A Panasonic spokesperson declined to comment.

Natural trade-off?

So even when global electric vehicle firms like Tesla – whose CEO Elon Musk made headlines last year when he promised a “giant contract” to any mining company that can supply him nickel mined in an “efficiently and environmentally sensitive way” – have pledged to protect the environment, stakeholders remain wary.

New nickel mining activities may invite more damage to the country’s biodiversity, and leave affected communities of mining sites without alternative livelihoods once the projects are finished. The promise of “clean” minerals is also vague as there is no clear definition for the industry, campaigners and experts said.

For Jose Bayani Baylon, Nickel Asia’s spokesperson, the idea of mining to support clean energy transition is part of how human development has been a series of tradeoffs. “I think that the reality is, unless you can grow it, or unless you can make it in a lab, you got to mine it,” he said.

Baylon said mining, if done responsibly, would fuel the country into the green economy. As for irresponsible miners, the government needs to step in and enforce rules.

Rio Tuba’s track record speaks for itself, he said. The company has won multiple recognitions, including the Best Practice in Minerals Mining award in the first Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ Mineral Awards in 2017.

“We cannot castigate a whole industry because there are some irresponsible operators and there are, especially in the third world as you should expect,” he said. “Life has been a series of tradeoffs, and we’re still trading off. But I think the trading off now is getting much better than it was.”

PCIJ met with Bataraza Mayor Abraham Ibba in Rio Tuba in October. He initially agreed to be interviewed but later refused, saying he could not talk about the issue until after the elections. PCIJ also tried to reach him in November but he did not take the call.

The Municipality of Bataraza initiated the change in the land use plan and environment zoning of Mt. Bulanjao, which triggered the issuance of a clearance needed by Rio Tuba to apply for expansion.

PCIJ also sought an interview with Palawan Gov. Jose Alvarez who chairs the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), the agency that issued the clearance to the mining company. Alvarez forwarded PCIJ’s request to PCSD staff.

PCSD Executive Director Teodoro Jose Matta said the tradeoffs were obvious given that mining would affect communities. But the national economy, which needs to recover amid the pandemic, was also one of the considerations that PCSD took in issuing clearances to Rio Tuba and other companies.

“So, where are you going to get that money? It’s these industries themselves that make that money, and I’m hoping they’re honest enough to declare their… true income,” he said.

Matta said PCSD was also putting pressure on the MGB to realign miners’ Social Development and Management Programs (SDMP), as well as on the mining companies to give more aid to the province. Under the implementing rules and regulations of the Philippine Mining Act, mining companies are required to spend at least 1.5% of their operating costs for SDMPs, which include alternative livelihoods for communities that host mining sites.

Records showed that the consolidated SDMP programs of Rio Tuba and Coral Bay amounted to P251.8 million from 2004 to 2008 and P615.8 million from 2009 to 2013. The program covered expenses for hospital services, school subsidies, walk-in community relations assistance, housing, an indigenous learning system, community development, and training.

“Yes, it has come to our attention that there should be a payoff – a trade-off between the exploitation of the environment in the community apart from the employment that the company generates, or the small businesses that ripple around these operations, and we will be pushing very hard that they give more than is prescribed under the law,” Matta said.

Nickel prices have gone up due to the high demand. “If they’re raking it in, what’s a couple of P100 million in CSR (corporate social responsibility) to help the local community?” Matta said.

Nickel Asia is one of few companies that profited during the pandemic. In fact, its profit by the end of 2020, P4.07 billion (US$79.36 million), was the highest in four years. This was a 51% jump from the previous year’s record of P2.7 billion.

Nickel Asia said it benefitted from the continued export ban in Indonesia, which holds the world’s largest nickel reserve. The company also enjoyed higher ore export prices in 2020, at US$33.99 per wet metric tonne (WMT), 45% up from the previous year.

The Rio Tuba mine accounted for more than a quarter of Nickel Asia’s exports in 2020, at 1.98 million WMT of saprolite ore and 3.03 million WMT of limonite ore.

‘Projects lacked sustainability’

Economist Cielo Magno warned that without policy reforms, the growing demand for nickel would take a toll on host communities. A 2016 assessment by Bantay Kita, a coalition of civil society organizations that seeks to promote transparency in the extractive industry, found that alternative livelihoods were hardly offered in communities that previously hosted mining projects.

Magno is an economics professor at the University of the Philippines – Diliman and the civil society representative in the international board of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI). She also previously coordinated Bantay Kita and was a founding member of EITI Philippines.

In the report, Bantay Kita detailed how the SDMPs of mining companies lacked sustainability. The SDMPs the organization studied relied largely on the continuous support of mining operators to keep projects in place.

“Mining companies can extend support either directly (e.g., salary support for teachers, financial assistance to cooperatives) or indirectly (e.g., livelihood projects where companies serve as the principal end-users). In the absence of an alternative support mechanism, such projects or activities tend to fail once the mining projects are terminated and companies move out of the community,” the report said.

Even the tax regime is tilted toward miners, Magno said, noting that companies only paid 46% of the value of their mined nickel output on average.

“At the moment, the government, and the industry, are only seeing the (financial) potential for demand for nickel but they are not seeing what is the real impact of mining at the community level especially with regards to poverty alleviation,” she says.

Garganera of ATM echoed Magno’s sentiment, saying that “rational” mining should be practiced in the country. “With the climate crisis, the mining industry has to be beneficial enough for our country to be pursued… This means the industry should be ready to invest in the next generation, and we could do that with an establishment of a wealth fund that the country can use.”

Ways forward

A fund that the government can tap for the development of provinces and communities affected by mining sites is being pursued in Congress, under House Bill No. 6135 or the Fiscal Mining Regime Bill.

The measure proposes a Natural Resource Trust Fund from the revenues to be collected from a margin-based royalty paid by large-scale metallic mining operations, for projects that will benefit local governments directly affected by mining activities. The bill, however, remains pending in the House of Representatives.

Another proposal that has not been discussed more prominently in the local mining community is the recycling of available metals. In April 2021, the Institute of Sustainable Futures of the University of Technology Sydney released a report detailing how recycling end-of-life electric-vehicle batteries can decrease demand for new mining.

“Recycling has the potential to reduce primary demand compared to total demand in 2040, by approximately 25% for lithium, 35% for cobalt and nickel and 55% for copper,” the report said.

Magno said investments of mining companies in the Philippines could be funneled to the development of recycling facilities that would not only decrease mining activities in the Philippines, but also generate new, alternative jobs for affected communities.

But Holden of the University of Calgary is skeptical about the Philippines’ prospect in becoming a recycling hub of used metals. “Recycling would take a global approach to be effective,” he said. “In the European Union (EU), there are already policies in place, but in developing countries, I’m skeptical.”

Under the EU’s waste management system, up to 40% of electronic waste is already recycled. In 2018 alone, for example, 94 million tons of scrap steel have been utilized by the bloc, equivalent to all automobiles circulating in France, the UK, and Belgium, said the European Recycling Industries’ Confederation (EuRIC), a confederation of recyclers in the region.

The EU is in the process of increasing this number, with the adoption of the Circular Economy Action Plan in March 2020. Part of the plan is to provide mandates that would require manufacturers to only design and sell electronics that are repairable and recyclable.

This is part of the EU’s bid to be “climate neutral” or to be an economy that emits zero carbon emissions by 2050.

In contrast, members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) have mostly relied on the informal sector to recycle their waste, as reported by the United Nations in 2020. Recycling initiatives have also mostly focused on plastics, and not metals.

This underscores Garganera’s sentiment on the lack of pressure from the international community, especially in the Asia Pacific, to impose better practices in any industry that may harm the environment.

“Policy-wise, I have very low confidence on any agreement at the Asean level that can be meaningful and relevant to environmental and human-rights concerns… They [practice] non-interference policy,” Garganera says.

For the environmental activist, he would rather hope for better regulation from authorities in the Philippines. Existing laws and policies are beneficial if implemented properly, he said.

“Standards for extractives will not improve [in the Philippines], unless our internal mechanisms to monitor and [check] accountability of mining operations are set at a higher standard than what we are doing right now,” he said. –PCIJ, December 2021

==

Andrew W. Lehren is a senior editor with the NBC News Investigative Unit and a fellow with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

Anna Schecter is a senior producer with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Rich Schapiro is a reporter with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Rachel Ganancial of Palawan News and Sofia Bernice Navarro, Ma. Cecilia Pagdanganan, Kyla Ramos and Martha Teodoro of PCIJ contributed research to this story.

Photographs: Kimberly dela Cruz

Infographic: Joseph Luigi Almuena with NBC News research