By Francis Allan L. Angelo

A proposal by the Philippine Ports Authority (PPA) to relocate the Roll-on/Roll-off (RoRo) operations from Dumangas town in Iloilo province to Fort San Pedro in Iloilo City is raising alarms from a local think tank warning that the move may undermine both the city’s heritage and its livability.

The plan aims to centralize RoRo transport in Fort San Pedro, a historic area undergoing restoration, in hopes of transforming Iloilo into a major maritime hub in Western Visayas.

PPA Panay-Guimaras Port Management Office manager Allan Rojo earlier said, “This is to make Iloilo a hub where all RoRo operations are centralized in the city itself.”

The plan aligns with a directive from Transportation Secretary Vince Dizon to explore a new RoRo port at Fort San Pedro to “boost the area’s economic potential.”

But analysts warn this approach contradicts global best practices and might harm Iloilo’s long-term development.

A proposal by the Philippine Ports Authority (PPA) to relocate the Roll-on/Roll-off (RoRo) operations from Dumangas town in Iloilo province to Fort San Pedro in Iloilo City is raising alarms from a local think tank warning that the move may undermine both the city’s heritage and its livability.

The plan aims to centralize RoRo transport in Fort San Pedro, a historic area undergoing restoration, in hopes of transforming Iloilo into a major maritime hub in Western Visayas.

PPA Panay-Guimaras Port Management Office manager Allan Rojo earlier said, “This is to make Iloilo a hub where all RoRo operations are centralized in the city itself.”

The plan aligns with a directive from Transportation Secretary Vince Dizon to explore a new RoRo port at Fort San Pedro to “boost the area’s economic potential.”

But analysts warn this approach contradicts global best practices and might harm Iloilo’s long-term development.

According to Iloilo-based think tank Institute of Contemporary Economics, the proposal reflects a form of “shotgun development” that disregards evolving urban design standards and economic logic.

The Port of Iloilo has historically been central to the region’s prosperity, dating back to its opening for international trade in 1855.

Its strategic location once fueled the growth of the sugar industry, leading to infrastructure investments such as a railway network in Panay, Negros, and Cebu.

By 1907, the Philippine Railway Company was transporting sugar and molasses to the Port of Iloilo, solidifying its role in Western Visayas’ industrial economy.

But this economic trajectory reversed dramatically after the Laurel-Langley Agreement ended in 1974.

The collapse of sugar prices in 1975, from 67 cents to 13 cents per pound, devastated the protected Philippine sugar industry.

The resulting poverty, especially in Negros, eventually led to the closure of the Panay Railway in 1983.

Simultaneously, the Iloilo port area became notorious for crime and decay, pushing the city into decline.

Rehabilitation began in the 2000s, with the City Government restoring order and building ferry terminals to Bacolod and Guimaras.

More recently, the concession to operate the Iloilo Commercial Port Complex was awarded to Visayas Container Terminal, Inc., signaling renewed investment.

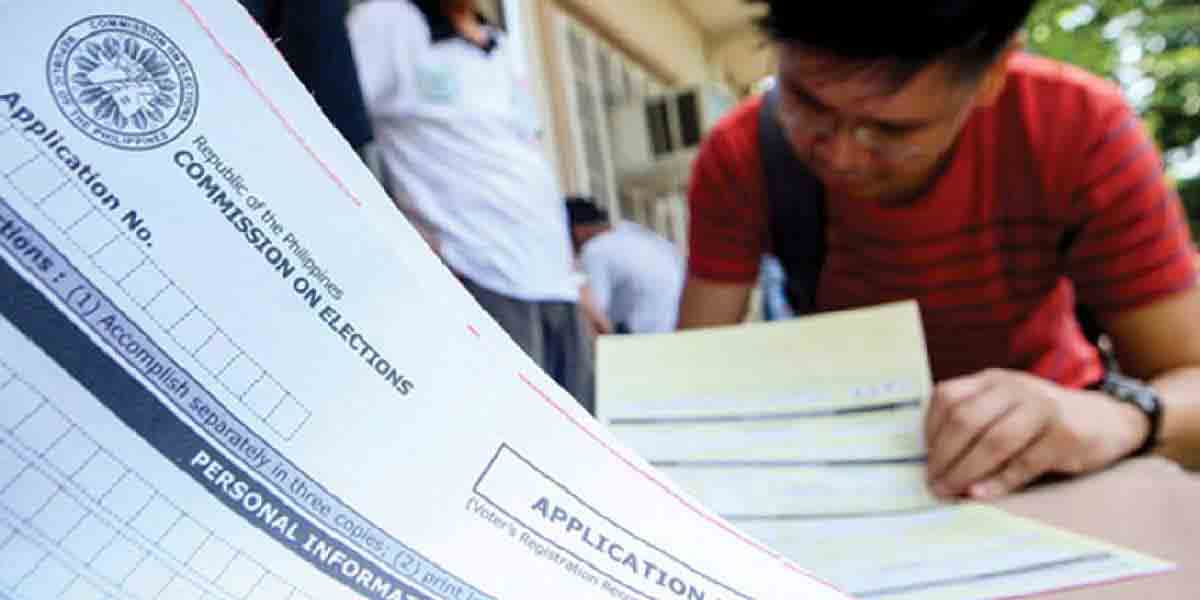

The push to move RoRo operations to Fort San Pedro has surfaced under the context of the Philippine Nautical Highway System — also known as the Road Roll-On/Roll-Off Terminal System (RRTS) — launched in 2003 to integrate highways and ports across the country.

Yet, critics argue the plan is a logistical misstep.

The Dumangas port is strategically located along the Western Nautical Highway, serving as a direct conduit between Panay and Negros.

Relocating to Fort San Pedro would add 20 kilometers to each leg of the route, as vessels would need to backtrack around the northern tip of Guimaras.

This roundabout detour adds roughly 40 kilometers per trip, inflating fuel costs, extending transit time, and potentially increasing passenger fares.

Economists also point to inefficiencies and legal complications arising from the use of Iloilo City streets for RoRo-related cargo and buses.

Existing city ordinances — 2002-408, 2004-268, and 2006-010 — limit the movement of provincial vehicles within city boundaries.

The influx of heavy cargo and passenger vehicles could congest already busy roads, raise safety risks, and violate local policies.

This raises a key question: where will a new terminal for incoming provincial buses be built, and who will shoulder the cost?

Meanwhile, cargo trucks from RoRo vessels would navigate narrow city streets, further delaying deliveries and increasing shipping costs.

The transfer also threatens the integrity of Fort San Pedro, a cultural and historical landmark currently being restored.

Despite PPA assurances, critics say the increased vehicular traffic and pollution will degrade the site and undermine tourism efforts.

“The road congestion will have the effect of cutting off the Fort San Pedro site,” the analysis states.

In a few years, the Iloilo-Guimaras Bridge is also expected to render RoRo routes to Guimaras obsolete, making the investment in a new RoRo hub redundant.

“The completion of the Iloilo-Guimaras will negate the need for a RoRo to Guimaras,” the study notes.

The economic benefits touted by project proponents also remain unclear.

Beyond unproven gains, the relocation risks displacing service providers and workers based in Dumangas, resulting in zero-sum outcomes that simply redistribute — rather than grow — economic activity.

The Institute warns, “Don’t fix what’s not broken.”

It suggests that while the Lapuz RoRo port may require improvements, targeted solutions such as traffic management or parking upgrades would be more cost-effective and less disruptive.

“There is no need to use a bazooka for a problem that can be fixed with existing tools,” the group emphasized.

The broader issue lies in redefining what progress means for Iloilo City.

While economic growth is essential, livability — measured in terms of congestion, access, and quality of life — must also guide policy.

Iloilo’s waterfront has historically been its engine of growth, and urban planners argue it could again serve as a catalyst for inclusive development.

The area around Fort San Pedro, bounded by Ortiz/Muelle Loney and Fort San Pedro Drive, spans 84 hectares populated by informal settlements, small businesses, and government facilities.

Revitalizing this space into a vibrant waterfront — integrating offices, public parks, and residential zones — would yield long-term economic and social dividends.

International models support this approach.

According to Port Economics, Management and Policy by Notteboom, Pallis, and Rodrigue (2021), many modern cities have redeveloped their waterfronts as post-industrial hubs for tourism, leisure, and housing.

“In recent decades, the prevailing trend has been a growing level of divergence between ports and their host cities,” the authors wrote.

Factors driving this shift include the migration of terminals to peripheral areas, reduced labor needs from automation, and increased security restrictions at ports.

These trends have allowed cities to reclaim their waterfronts for public use while relocating industrial operations to less congested locations.

“Iloilo City is not alone,” the Institute wrote. “Many cities worldwide have built an intricate relationship with their port since they owe their origin to their port site.”

The group argues that rather than reverting to industrial use, Iloilo should aim for “transformative redevelopment” that improves lives without displacing communities.

“If done right, this could again elevate Iloilo City in the manner that this same area did in the 1800s,” the Institute wrote.

The call is not for marginal or cosmetic upgrades but for bold urban reinvention grounded in global experiences.

From economic history to modern logistics and urban theory, the evidence appears stacked against the proposed RoRo port shift.

As Iloilo weighs its options, stakeholders will need to consider not only what’s expedient — but what’s visionary.