By Carmela Fonbuena

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

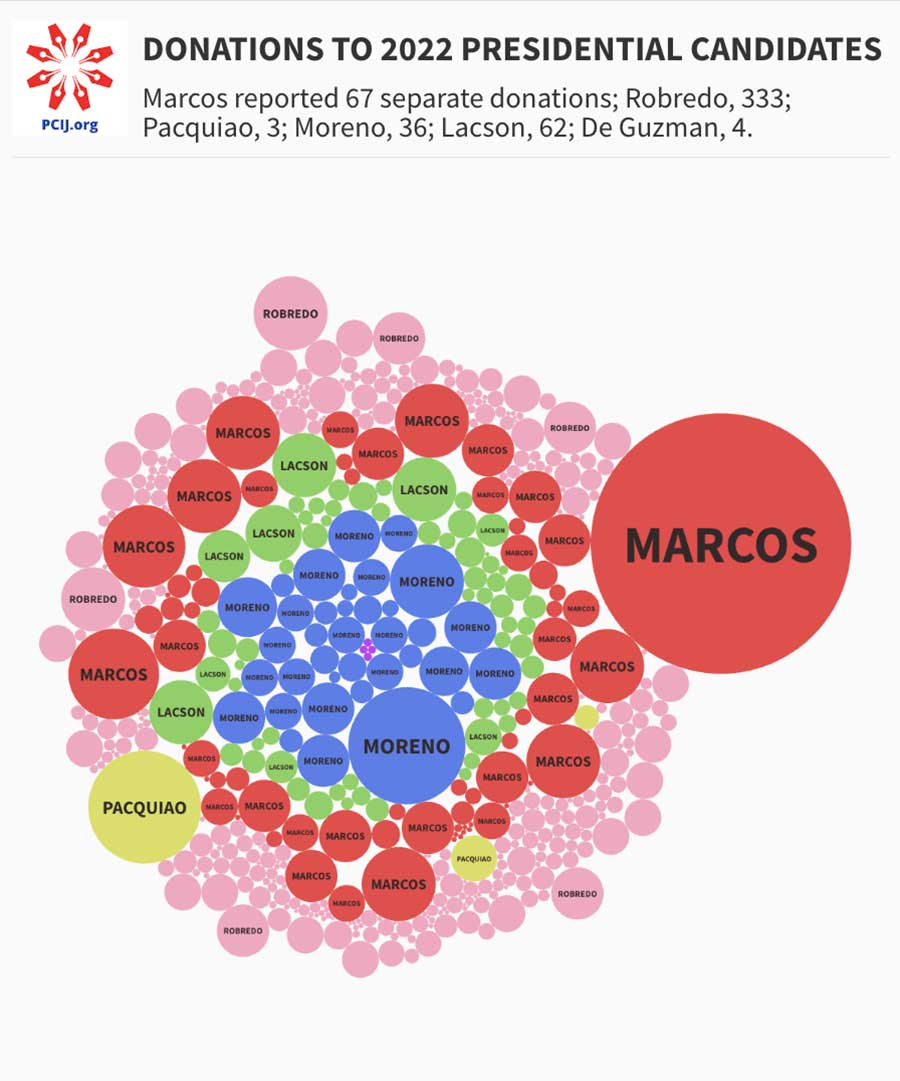

The list of donations to former Vice President Maria Leonor “Leni” Robredo’s historic albeit unsuccessful campaign in the May 2022 elections is a long one.

She received 333 individual donations from a total of 307 individuals — a few of them giving more than once, based on her disclosures to the Commission on Elections (Comelec).

It’s an unprecedented number seen in the Statement of Contributions and Expenditures (SOCE) of presidential candidates in Philippine elections.

Most leading presidential candidates reported receiving the bulk of their donations from donors who gave at least P10 million, an amount that could purchase high-end condominiums in the country’s capital. Robredo only had six of these big-time donors.

In terms of the number of separate donations, most of Robredo’s donors gave less than P1 million each. There were so many of these small donations — 208 out of 333 — that the total amount was not that far from the contributions made by her top donors.

Robredo’s six biggest donors, who donated P10 million to P20 million each, gave a combined amount of P75 million. It was 19% of her total campaign fund.

Meanwhile, the small donations added up to P56.9 million or 15% of her campaign war chest.

The amount of donations she received showed the general profile of her donors, said election lawyer Emil Marañon, who volunteered his services to the former vice president’s campaign in the 2022 elections.

“Makikita mo na maliliit ang donors ni VP precisely because ‘yung concept niya ay ‘People’s Campaign’ (You will see small donors giving to the VP precisely because her concept was a ‘People’s Campaign’),” he said.

“This is actually the ideal direction for campaign finance. Mas maliit ang ibinigay na donations, mas maliit ang chance na magkaroon ng utang na loob ang kandidato (The smaller the amounts of donations received, the smaller the chance of the candidate owing favors),” he said.

Marañon did not process donations during the campaign.

Lawyers, bankers, academics, artists

The small donations to Robredo came from professionals like lawyers, bankers, and academics who work in big corporations and institutions but do not own them or belong to top-level management. There was a doctor and an architect. There were artists, jewelry designers, and salon operators, among others.

The list also included political allies or their family members such as former Quezon representative Lorenzo Tañada III, Robredo’s colleague at the Liberal Party (LP).

The smallest donation amounted to P5,000 in cash from a humanitarian worker who actively campaigned for Robredo on social media. A few donors gave small amounts more than once.

The list of donations in Robredo’s disclosures was so long it took 16 pages. Her rivals, including President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., had one or two pages.

Robredo’s total donations amounted to P388.33 million. She added P19,778.99 from her own pocket, putting her total to P388.35 million. It’s equivalent to spending almost P6 for each one of the 65.7 million registered Filipino voters.

She was second to Marcos in terms of total donations received.

Only 6 big donors

Robredo’s biggest donors were former senator Sergio Osmeña III and lawyer Vibenditho Jimenez Piñga. They gave P20 million and P15 million, respectively.

Osmena is also Robredo’s colleague at the LP. He belongs to one of Cebu’s political and business dynasties.

Despite her membership in the LP, Robredo decided to run as an independent candidate. She galvanized passionate supporters all over the country who packed her campaign rallies. Her crowds were unmatched by other candidates including Marcos.

Running as an independent also meant that Robredo did not get the support of a political party.

In comparison, Marcos’s political party reported additional donations amounting to P273.67 million.

Robredo’s second top donor, lawyer Vibenditho Piñga, is a lawyer at the Piñga Law Office in Makati. He was named the country’s 77th top taxpayer in 2013.

Four other donors gave Robredo P10 million each. They are:

- Pilar Camins Yu, owner of the Camins Yu Enterprises

- Geraldine Desiderio Garcia, senior vice president the of Country Bankers Insurance Group

- Mark Alejo Santos Bernal, advertising and brand management executive

- and Ramon Del Rosario Jr., CEO of Phinma Corp., a holding company with investments in the education, steel products, housing, and business process outsourcing sectors.

Biggest bulk: P1-M to P5-M donations

In terms of combined amount, the biggest percentage of Robredo’s campaign funds came from 119 donors who gave separate donations worth P1 million to P 5 million. Their combined contributions amounted to P256.42 million or 66% of her entire funding.

Among the donors who gave Robredo at least P1 million but less than P10 million are the following:

- SEAOIL Foundation, Inc. Executive Director Victorio Joseph Ramoso Lorenzo, who gave three separate cash donations of P2.5 million totaling P7.5 million. Another SEAOIL Philippines Inc. executive donated twice to the campaign, totaling P1 million;

- Two independent board directors of the Lopez-owned First Gen Corp. who donated P5 million each, and another major shareholder of the company contributing the same amount. First Gen Corp. operates fossil gas and geothermal plants;

- A senior executive and an independent board director at power distributor Meralco, who contributed P5 million each.

Fifty-nine donors gave P1 million and 23 others gave P5 million to Robredo. Others in this middle bracket are executives of listed companies, like Ayala Corp., Globe Corp., and Unionbank of the Philippines.

A million pesos is not peanuts, nor is P5 million. But these are relatively smaller amounts compared with the donations usually seen in SOCEs of presidential candidates including in past elections.

In comparison, Marcos and other leading candidates largely relied on donors who gave at least P10 million.

For Marcos, the combined total of donations amounting to at least P10 million added up to P532.23 million. That was equivalent to 85% of his entire campaign funds, which totaled P624.68 million.

Marcos’s biggest donor was his own party, the Partido Federal ng Pilipinas, through party treasurer Antonio Ernesto “Anton” Floirendo Lagdameo Jr., grandson of a close business associate of his father, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos. This single donation footed 40% of Marcos’s campaign bill.

Marcos received only P1.55 million from a few donors who gave less than P1 million, many of them lawyers who contributed “in kind.”

Other presidential candidates

Other leading presidential candidates in the 2022 campaign also relied on big donors.

Former Manila Mayor Francisco “Isko Moreno” Domagoso received P153 million from donors who gave at least P10 million. The combined amount added up to 63% of his campaign funds.

His biggest donors were Andrea Chua and Allan Berenguer, who gave P50 million and P20 million, respectively.

He reported only P500,000 in small donations.

Former Sen. Panfilo Lacson had a short list of 62 donors. He received P66.7 million in big donations, accounting for 42% of his campaign funds.

The biggest chunk of Lacson’s campaign funds – a little more than half or 54% of the total – also came from donors who gave at least P1 million but less than P10 million.

The rest are small donations – less than P1 million – totaling P6.9 million.

A certain Crisinciano Mahilac who turned over donations worth P65.49 million was Lacson’s biggest contributor. He gave nine separate donations in the form of “cash from others” and “in-kind from others” such as face masks, shirts, arm warmers, and caps.

Two other donors gave P10 million each: Benjamin Go and Angelica Desiderio.

Labor leader Leody De Guzman received four separate small donations from his own party — Partido Lakas ng Masa (PLM) — worth P250,000 or a total of P1 million. It was the entirety of his campaign kitty, based on his disclosures.

Pacquiao paid his way

Sen. Emmanuel “Manny” Pacquiao, the richest candidate in the 2022 elections based on Statement of Asset, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN), pulled out of his pocket to fund his campaign.

He received P46.45 million from a single donor – Archinet Intl. Inc. The amount was 82% of his entire donations, which totaled P56.45. His campaign manager, businessman Buddy Bayan Zamora gave two separate donations totaling P10 million.

But a bigger amount, P62.68 million, came from Pacquiao’s own pockets, putting his total to P119.13 million.

Pacquiao reported zero small donations.

The former professional boxer reported a net worth of P3.2 billion in 2020. Marcos, based on his last available SALN in 2015, reported a net worth of P200 million.

The other candidate who funded his own campaign was Jose Montemayor. He spent P100,000 of his own money and reported zero donations.

Tedious reporting discourages small donations

Robredo and many other candidates, including Marcos, very likely had many more small contributions that were not declared in their SOCEs, according to election experts.

The 2022 campaign saw bitter division among voters, many of whom ran their own campaigns to support their candidates.

This is a challenge for campaign finance reporting, said Eric Alvia, secretary general of the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections.

“Even if we want to (monitor), you cannot. How will you account for donations that are used for local consumption? Not even the candidate knows that [people are] donating to him or her,” said Alvia.

It could be tedious to report small amounts even if the candidates knew about these small donations, Marañon said.

Donors are required by law to submit reports of contributions, which need to be sworn and notarized. Marañon said the responsibility is often shifted to the candidate’s campaign team.

“What other politicians would do, they would not declare the small amounts they receive,” he said.

Campaign finance rules were designed for big donors, Maranon said. While the reporting requirements are necessary to facilitate transparency, there should be a separate set of rules to make it easy for candidates to receive small donations, he said.

“There has to be full disclosure on big donations as envisioned by the report of contribution. The harm that we assume on big donations does not exist on de minimis donations so they should be governed by a different set of rules founded on ease and convenience.” — with reports from Elyssa Lopez

ILLUSTRATION BY JOSEPH LUIGI ALMUENA