By Annie Ruth Sabangan, Robert JA Basilio Jr., Bernard Testa and Ric Puod

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Part 1 of 4

What you need to know about Part 1:

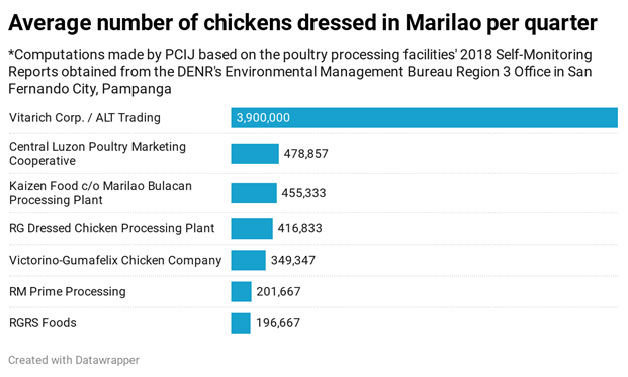

- The town of Marilao in Bulacan province has the biggest number of chicken dressing plants nationwide, slaughtering more than 24 million chickens yearly.

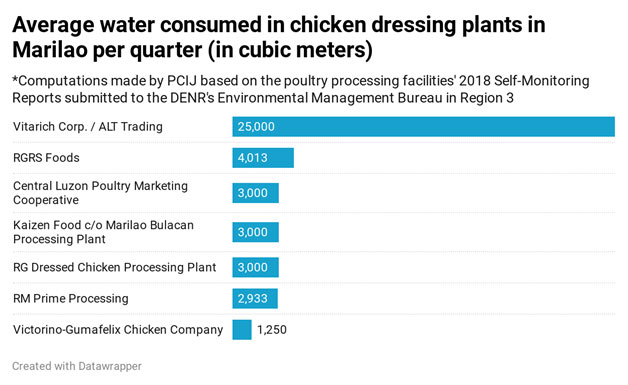

- The annual operations of chicken dressing plants in Marilao produce an estimated 169,000 cubic meters of wastewater or enough to fill up 68 Olympic-size pools.

- This huge volume of wastewater is regularly released into the Marilao River, a major tributary of the Manila Bay, which was declared biologically dead in 1989.

- Lack of resources and personnel prevents municipal government offices from gathering sufficient evidence to establish the extent that the dressing plants are responsible for the pollution of the river.

- There were efforts to revive the river, but so far failed.

You know you’ve reached Marilao, a booming municipality in Bulacan province that’s usually less than an hour’s drive from Manila, when a putrid smell of some biological degradation invades your nostrils. Here you will find a cluster of chicken dressing and rendering plants, which have become undesirable landmarks for the town in Central Luzon.

“Kapag sumasakay ako ng jeep galing Muzon, kahit nakapikit alam kong nasa Marilao na ako dahil sa amoy (When I ride a jeep from Muzon, I can tell that I’m already in Marilao even when my eyes are closed because of the smell),” said a female resident, referring to her regular commute to Brgy. Sta. Rosa 1 in Marilao from Brgy. Muzon in nearby San Jose del Monte City.

Marilao’s foul odors, coming from the Marilao River and its tributaries, are so notorious that it is the occasional subject of contempt on social media. The culprit, according to residents, are the poultry processing plants in the adjacent barangays of Santa Rosa I, Santa Rosa II, Patubig, and Loma de Gato that release wastewater to the river.

The smell is worse during dry season, residents said, when there’s no rainwater to dilute and dull the odor of the polluted water.

“Bata pa ako naaamoy ko na ‘yan. Ang anak ko, may asthma. Sabi ng pedia huwag siyang i-expose sa amoy at huwag paglaruin sa daan. Mahina raw kasi ang baga niya (I’ve been smelling that foul odor since I was young. My child has asthma. The pediatrician said he should not be exposed to the smell and should not play on the street because his lungs are weak),” said another resident operating a carinderia or eatery in the same barangay.

Marilao has the country’s biggest number of poultry processing facilities, slaughtering tens of millions of chickens annually to supply fresh and freshly frozen food to consumers nationwide.

Of the 149 poultry dressing plants accredited by the Department of Agriculture’s National Meat Inspection Service as of November 2019, almost one-fourth or 34 facilities are in Region 3 or Central Luzon. (See infographic 1)

Twenty are operating in Bulacan province and 11 of them are in Marilao. The industry was among the top employers in the town, according to the Business Permit and Licensing Office, with each plant providing jobs to about 300 residents. (See infographic 2)

It’s a thriving industry that has helped turn Marilao into the richest town in the province, tripling its revenue in the last decade to P793 million in 2018.

Like many industrial towns in the country, however, Marilao has struggled to strike a balance between economic growth and environmental protection.

Poultry processing uses water to turn broilers into meat products that are safe for human consumption. In Marilao, wastewater from the establishments flow into waterways connected to the Marilao River.

Seven of the 11 poultry processing facilities in the town discharge their effluents to a creek, either from the “rear end of the last pond,” “compartment,” or “tank” of their wastewater treatment plants, based on self-monitoring reports (SMR) that the plants filed with the DENR in 2018. (There is no data available to PCIJ on the other four dressing plants.)

The same seven dressing plants reported using nearly 169,000 cubic meters of water annually to slaughter 24 million chickens. That’s enough wastewater to fill up 68 Olympic-size swimming pools. (See infographic 3.)

Water is a huge requirement for poultry processing plants. Workers dip the heads of the chickens into electrified water to put them to sleep, and use hot water to loosen and pluck the feathers. They need chlorinated water to wash equipment for removing the chicken’s internal organs and thoroughly rinsing their carcasses. They also use chilled water to protect poultry meat from bacteria.

Foodnorthwest.org, a trade association in the U.S., estimates that approximately 3.5 to 7.0 gallons of water is required to dress each chicken with an average slaughter weight of four pounds. Using this ratio, PCIJ computation shows that between 10 billion and 19 billion liters of water were used to slaughter 763 million heads of chicken killed for food in the Philippines in 2019, based on figures from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

If untreated or undertreated, wastewater from the plants releases oxygen-depleting and fish-killing pollutants such as ammonia, nitrate, phosphate, and total suspended solids.

The succeeding parts of this investigative series will show evidence that this was the case in Marilao.

Residents’ complaints

Residents have long complained about the operations of the poultry processing plants, believing that their constant exposure to the foul odors has aggravated their illnesses.

“Diyan nanggagaling. Abot ang amoy hanggang doon sa bahay namin sa Patubig (That’s where it comes from. The smell reaches our house in Brgy. Patubig),” complained an aging female tuberculosis patient. She particularly blamed a big poultry processing plant in Brgy. Santa Rosa 1 near the Marilao exit of the North Luzon Expressway, for the reeking smell of Sapang Alat (Salty Creek), a clogged and heavily polluted creek adjoining the Marilao River.

The Municipal Health Office (MHO) is aware of the residents’ complaints and their concerns about the possible dangers to their health, according to Evelyn San Miguel, one of only two sanitation inspectors at the MHO.

She also has a good view of the outfall from the compound of one of the poultry processing plants –– where the liquid waste from its plants falls out from its pipe –– from a window of the MHO building. “Brown ‘yung inilalabas (The discharge is colored brown),” San Miguel said in an interview in September 2019, the same month that PCIJ sailed into Sapang Alat.

San Miguel said they forwarded these complaints to the Business Permit and Licensing Office (BPLO) and the Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Office (MENRO).

The chief of the BPLO, Martin Armando Cruz, downplayed the residents’ complaints, however. While the poultry business was the most “water-intensive” of all industries in Marilao, he told PCIJ he didn’t think the poultry business was among the most pollutive.

Cruz said the poultry processing plants were releasing chlorinated but clear water, a claim that was contradicted by other interviewees for this report and PCIJ’s own findings.

“‘Yung wastewater naman nun puti…. Madaling i-clear [kasi] walang chemicals e. Chlorine lang. Kayang-kayang linisin (The wastewater they release is white…. It can easily be treated because there are no chemicals. It’s just chlorine. It’s easy),” Cruz told PCIJ in an interview in October 2019, referring to the effluents discharged by the dressing plants.

Cruz conceded that the fetid odor from the plants, particularly from the town’s biggest plant along Sapang Alat, were a nuisance. But he didn’t think it was the cause of the illnesses of Marilao residents.

“Yes, [it’s a] nuisance. But is it pollutive? Nakamamatay (Is it deadly)? Nakakasakit (Does it cause illnesses)? Sa aming observation, hindi naman (Based on our observation, it’s not),” Cruz said.

Cruz was inclined to believe that domestic wastes caused more harm to the river than the wastewater from Marilao’s industries, although he admitted that the LGU had made no assessment of the chicken dressing industry’s wastewater.

“Hindi kasi kami nagtse-check no’n, wala kaming testing ng water…ang DENR ang [in-charge] do’n (We don’t check that, we don’t conduct water testing…the DENR is the one in-charge of that),” said Cruz.

The residents interviewed for this story requested to hide their names out of fear that the business establishments would go after them for their comments.

A dead river

The Marilao River, a tributary of Manila Bay, has been biologically dead since 1989. It can no longer sustain any life form.

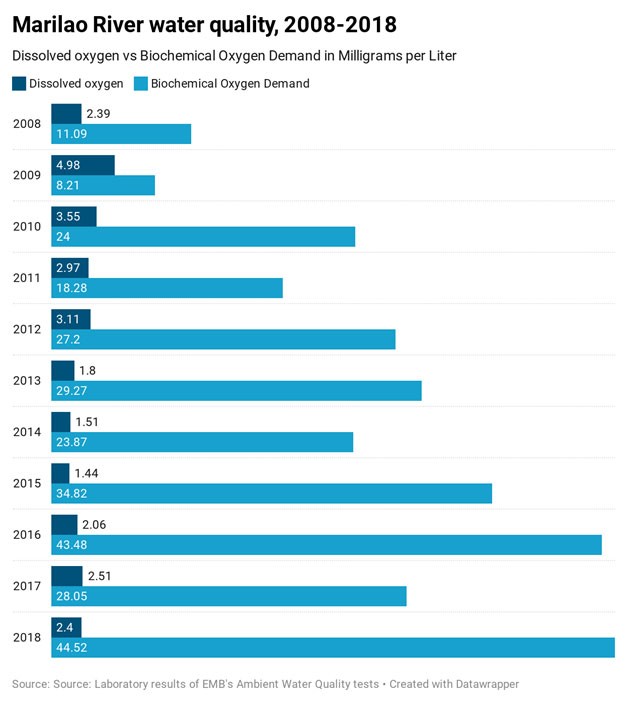

For fish and other aquatic species to survive and thrive in a freshwater resource like the Marilao River, the water body needs to contain 5 milligrams of dissolved oxygen (DO) per liter of water (mg/l), according to DENR standards.

But the DO levels in the river have not even reached 3 mg/l in the last decade, based on tests conducted by the Region 3 office of the DENR’s Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), which conducts ambient water quality tests on the river.

Scientists call this condition “hypoxia,” a depletion or reduction of oxygen in water bodies that turn them into “biological deserts” or “aquatic cemeteries.”

The river’s biological oxygen demand (BOD), which represents the amount of oxygen consumed by bacteria while they decompose organic matter in the water, has been rising, too.

The river’s BOD should not exceed 7 mg/l under better circumstances because, above that level, bacteria will use more oxygen to decompose wastes and thus rob fish and other aquatic animals of survival gas. However, EMB tests showed that the recorded BOD level of Marilao River was a high of 44.52 mg/l in 2018 or four times its level of 11.09 mg/l in 2008. It was an indication that pollution had worsened throughout the last decade.

This is a shared challenge among the industrial towns in Bulacan. The Marilao River is part of the Meycauyan-Marilao-Obando River System (MMORS), a heavily polluted river system that is considered the second top pollution source of Manila Bay.

MMORS is responsible for about a third of the organic matter going into the historic natural harbor in the country’s capital, next only to Pasig River, which accounts for 60%, according to a study by the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia, implemented by the United Nations Development Programme.

Other industries are polluters, too

While residents point to the responsibility of the poultry processing industry for the pollution of Marilao River, the local government doesn’t have the capacity to gather sufficient evidence to establish the extent that the industry is at fault.

The poultry processing facilities are certainly not the only polluters of the river, which is host to households and other types of industries that produce different types of waste. There are metal and textile factories, manufacturers of plastic products, biscuit and bread makers, and soap and detergent businesses, among others.

Which of these entities contribute the most pollutants to the river? What businesses or industry sectors have effluents with the highest BOD or ammonia? Which ones discharge the most volume of sludge laden with toxic and non-biodegradable heavy metals like lead, arsenic, and mercury?

Along or near the Marilao River’s Expressway Bridge alone — one of three water sampling stations in the river — there are almost 2,000 commercial entities spread in nine Marilao barangays. Tabing Ilog, Patubig, Sta. Rosa I, Sta. Rosa II, Saog, Lambakin, Loma de Gato, Prenza I, and Prenza II are the town’s business hubs.

The Region 3 office of the EMB also earlier identified 433 establishments in the entire Central Luzon whose wastewater flows into the MMORS.

Which ones among them don’t have wastewater treatment plants or have inefficient effluent cleansing facilities? What businesses are the worst river and fish killers? It would take special types of tests to determine all this.

In an interview in September 2019, when PCIJ was starting this investigation, Marilao Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Office (MENRO) chief Reynaldo Buenaventura admitted they still couldn’t measure the extent of pollution from particular plants or industry sectors because of lack of resources and personnel.

Marilao is only capable of employing “end-of-pipe” pollution solutions, which requires cleaning up wastes when these have already polluted the river, he said.

“May river patrol boat kami, dalawa, galing sa DENR. Araw-araw silang nagpa-patrol pero ‘yung solid waste lang ang nakukuha (We have two river patrol boats from the DENR. The boats patrol every day but they only collect solid waste),” Buenaventura said.

EMB’s usual ambient water quality tests, which gather “primary parameters” such as dissolved oxygen, biological oxygen demand, and other conventional pollutants, don’t trace the sources of pollution, either.

These tests can only give hints and symptoms of the water pollution problem in the Marilao River, but not its direct causes, said Glenn Aguilar, among the EMB staffers in Region 3 who monitor the river.

Failed efforts to revive the river

Several administrations attempted to revive the Marilao River, but efforts have failed to reverse its DO and BOD levels.

The Marilao River was among the 19 priority rivers monitored by the DENR under its “Sagip Ilog” (Save the River) Program, a 2004 initiative that sought to improve the river’s water quality by raising dissolved oxygen levels.

In 2004, the Marilao River Council was formed to rehabilitate the water body. A project called “Clean the Marilao, Meycauayan, and Obando River System” was launched, involving local government units (LGUs), the EMB, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, the river councils, and the Asian Development Bank. They envisioned a “fishable, swimmable, and drinkable” river system.

In 2005, Marilao became a part of a stakeholders’ group composed of the three LGUs that have jurisdiction over the MMORS. As a major tributary of Manila Bay, the heavily polluted river system in Bulacan became a focus of efforts to rehabilitate the natural harbor.

There was little to show for all these efforts, however. In 2007, Marilao, along with its neighbor, Meycauayan City, suffered global disgrace after New York-based environmental watchdog Blacksmith Institute included the town in its list of 30 “dirtiest places” on earth. The list raised an alarm over how the town’s industrial wastes were being “haphazardly dumped” into the river.

In 2008, the Supreme Court issued a continuing mandamus or order to the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) and 12 other agencies to clean up and preserve Manila Bay, resulting in renewed attention to the Marilao River. The mandamus stemmed from a January 1999 petition by a group of residents, who won the case in a Cavite court and the Court of Appeals. Ten government agencies, including the DENR and the DILG, appealed to the Supreme Court and lost.

The order prompted Marilao’s Municipal Planning and Development Office (MPDO) to conduct an inventory of commercial establishments and households adjacent to the Marilao River and its tributaries, supposedly to pinpoint pollution hotspots.

What did they find out? Nearly 60% of the 756 households identified did not have septic tanks, while 71% of 91 business establishments had no wastewater treatment facilities.

It was the first and last comprehensive inventory of households and businesses near the river, said Edmundo Canape, a senior staffer at the MPDO, who signed the 2009 report. Succeeding inventories would only check a percentage of the commercial establishments and households.

In 2011, the Supreme Court again issued a resolution enjoining government agencies and local governments surrounding Manila Bay to implement the 2008 mandamus. The high court cited the 42-year-old Presidential Decree 1152 or the Philippine Environmental Code, which requires all local governments to implement a waste management program.

Part of the directive was for LGUs to address water pollution at source by (1) inspecting all factories, commercial establishments, and homes along the banks of the major river systems in their areas; (2) determining if they have wastewater treatment facilities or hygienic septic tanks based on specifications prescribed by law; and (3) requiring non-complying establishments and homes to set up facilities or tanks within a reasonable time. Otherwise, they faced fines or closure.

Still, the pollution of the Marilao River continued to worsen.

In 2017, then Marilao Mayor Juanito Santiago issued Executive Order 2017-09 for the town to comply with the High Court’s 2011 resolution.

In 2018, the DILG flagged Marilao’s weakness in environmental governance. The municipality got a score of 45.91% in a DILG assessment and was one of 19 towns and cities in Bulacan that scored below the passing mark of 75%.

The DILG found that Marilao didn’t follow the Supreme Court directive when it inspected only 15% of the target number of septic tanks and wastewater treatment facilities. No single notice of violation was also issued by the LGU against establishments that failed to comply with Republic Act 9275 or the Clean Water Act of 2004.

The DILG also noted the town’s failure to relocate informal settlers living along the river banks.

No environmental officer for a long time

In the wake of its failing marks from the DILG, Marilao’s MPDO took new steps to address water pollution at source.

Based on a 2019 report provided by MPDO staffer Salvador Ramirez to PCIJ, they inspected about 1,000 homes in 16 barangays yearly — a small percentage out of some 50,000 total households — from 2016 to 2018. Notably, the inventory didn’t include business establishments.

The MPDO was simply undermanned. The office established the Marilao River Inspection, Inventory and Monitoring Team (MRIIMT) to attend to its old problem, but Ramirez said this team was a one-man squad.

“So that time…kami lang dito. Ako. Ako ‘yung bumababa (So that time…it was just us here. It was just me. I was the only one who went to the field to inspect),” said Ramirez.

It was only in 2018 that Marilao would create the Municipal Environment and Natural Resources Office (MENRO) and hire Buenaventura to become its environmental officer.

The Local Government Code of 1991 does not require the designation of an environmental officer. The town apparently never found the need to have one until Buenaventura was appointed to the post in January of that year. He would later assume the tasks from the MPDO.

In 2019, PCIJ asked Buenaventura if it was possible to send the LGU’s river patrol team to go after dressing plants found dumping untreated effluents into narrow, muddy and clogged tributaries.

Buenaventura dismissed it. “Hindi maaabot ng bangka ‘yun (That can’t be reached by the boats),” he said.

A PCIJ team discovered it was an arduous task, but it was doable under the right conditions. –– PCIJ, February 2021

This series was produced with the support of Greenpeace Southeast Asia-Philippines.