Up to 25 million tons of fish are estimated to be lost globally each year to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activity, known as IUU fishing. According to some officials, IUU fishing is now replacing piracy as the world’s top maritime security threat, undermining efforts to manage fish stocks sustainably, creating unfair competition for those who do follow conservation rules, and threatening food security and economic stability for many coastal communities worldwide.

But combating IUU fishing on a global scale is no simple task, to put it mildly. First there have to be enforceable laws and international agreements in place. Then IUU activity must be detected among the estimated 4.5 million fishing vessels plying vast areas of ocean worldwide, and surveillance data shared quickly between a jigsaw puzzle of nations and jurisdictions. And finally there have to be the enforcement resources to apprehend and punish offenders.

“It truly is going to take multiple nations and levels of engagement to counter the challenge,” said Admiral Linda Fagan, vice commandant of the US Coast Guard, at this year’s virtual Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Exchange. Experts advanced a variety of ways to tackle the IUU fishing problem at the recent conference, hosted by the Navy League of the US Honolulu Council in partnership with the East-West Center, the Daniel K. Inouye Center for Asia-Pacific Security Studies, and Pacific Forum. Each year, the conference focuses on a different topic to facilitate dialogue on maritime security issues in the region.

Prevention and treaties

Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, or RFMOs, are international bodies that coordinate efforts to manage fish stocks in a particular region. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, there are some 17 RFMOs in place covering different geographical locations, and many countries with large fishing fleets are members of several RFMOs.

While RFMOs can be effective at managing fish stocks in a particular region, some large parts of the ocean remain vulnerable to illegal activity. “Large areas within these RFMOs do include the high seas, or areas beyond national jurisdiction,” said Dr. Alex Kahl, a natural resources manager with the US National Marine Fisheries Service. “In the Pacific, these areas are particularly vast and remote, and this really requires collaborative international management measures and structures.”

Other international pacts, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and a binding 2016 global agreement to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing, have helped establish nations’ rights over marine resources. As an example of the kind of results international agreements can achieve, Adm. Fagan cited an incident last year when several hundred Chinese squid fishing vessels were operating in the vicinity of the protected Galapagos Marine Reserve off the coast of Ecuador. Due to existing agreements in place between Ecuador and the US, she said, the Coast Guard was able to redirect one of its ships toward the Galapagos, where it used a drone to detect evidence of illegal activity and was able to share that information with the Ecuadorian Navy for enforcement.

“We often like to say that it takes a network to counter a network,” Fagan said, “and this is the approach that we’re thinking about with regard to IUU fishing.”

High-tech detection

In recent years, high-tech surveillance methods have become increasingly effective in detecting IUU fishing. Tim White, senior fisheries scientist at Global Fishing Watch, explained that satellite tracking is being used to monitor the behaviors of fishing vessels, and artificial intelligence helps make better sense of large data sets. This information is then tracked in near real time and publicly released so maritime security professionals, governments, scientists and the general public can use it to help create solutions.

“We think that increased transparency in fisheries helps reduce IUU by making bad actors stand out more dramatically,” White said, noting that global watchdog groups can also incentivize good behavior. As an example, he cited satellite data compiled by Global Fishing Watch that detected thousands of fishing vessels, many from China, operating illegally inside North Korea’s exclusive economic zone. “This was one of the largest cases of IUU that we’re aware of in recent times, because the estimated catch for all these vessels over a couple-year window was nearly 440 million dollars,” White said. “Making use of the latest technology alongside analytical techniques can really shine a light on some IUU concerns that are addressable.”

Data sharing key

A recent study commissioned by The Pew Charitable Trusts found that fisheries that openly share data stand to benefit regardless of whether or not others follow suit, and increased information sharing can boost a nation’s ability to enforce maritime law.

Paul Woods, chief innovation officer and co-founder of Global Fishing Watch, discussed the need for key fishing nations to make their vessel tracking data public. Failure to get timely data often leads to lost opportunities in decision-making, innovation, and intervention capabilities, he said. In addition, a culture of compliance is created as more countries commit to data sharing.

Collaboration is particularly important for smaller coastal nations that may lack the resources to counter larger threats. “We’ve got to support small island developing states in not bearing inappropriate costs when they do intercept these fleets and then increase the cost on the countries from whom these vessels originate,” said Mark Zimring, large scale fisheries director at The Nature Conservancy.

Enforcement barriers

While many tools have been put in place to prevent and detect illegal activity, following through on enforcement remains a challenge across the globe. Coast Guard Captain Holly Harrison explained that even when IUU activity is detected, finding small targets in a vast ocean, inspecting the vessel and identifying catch, accessing ports, and overcoming language barriers can create impediments to maritime authorities carrying out the law.

“Having good legislation is one thing, and following through with effective implementations is quite another,” said Mok Lay Yong, a director of Malaysia-based maritime consultants Sharina Shaukat and Partners.

Regional conflicts, particularly in disputed areas like the South China Sea, can make enforcement efforts even more difficult. David Hogan, director of the Office of Marine Conservation at the US State Department, said that IUU fishing can often exacerbate conflict between competing vessels and between industrial and small-scale fisheries, as well as between countries. “As we see resource scarcity increasingly play a factor in deteriorating relationships, I think fisheries are more and more featuring into a much broader conversation about security at every level,” he said.

Market incentives

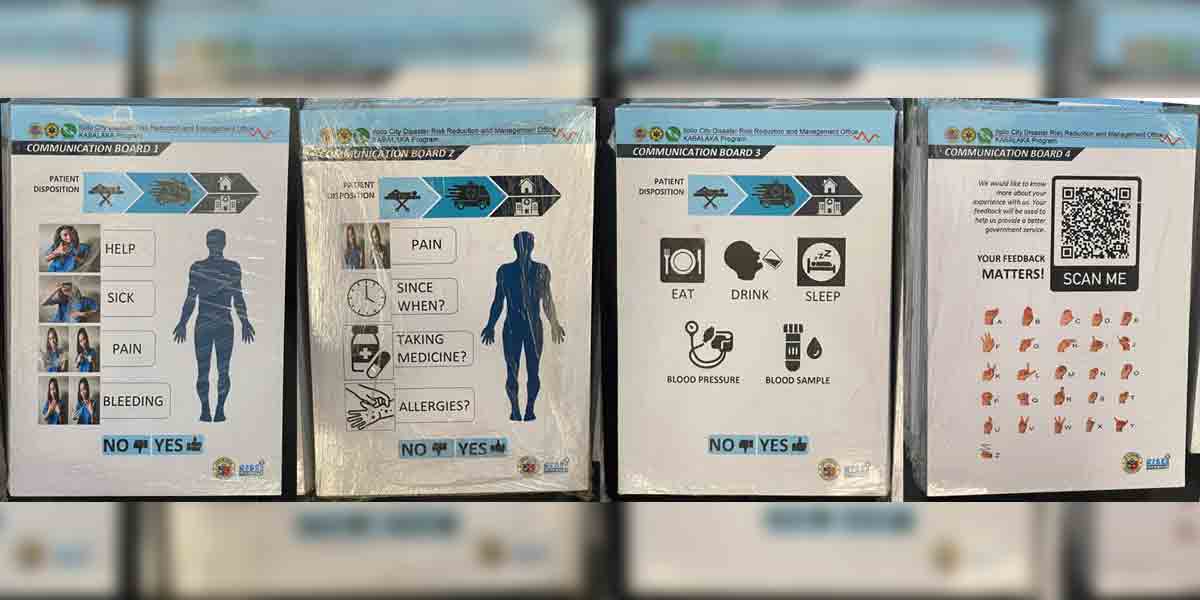

Dr. Amanda Ellis with Arizona State University’s Global Futures Laboratory spoke about the need for a “whole of government and whole of society approach.” In addition to policy change, she said, market incentives can help change corporate practices and spark consumer change. Ellis cited a pilot program that creates greater traceability between small-scale fisheries and consumers through tech like QR codes and blockchain-based systems.

Dr. Elizabeth Selig from Stanford University’s Center for Ocean Solutions discussed working with seafood companies to encourage more active roles in ocean stewardship. By utilizing available data from civil groups and government organizations, companies can determine where their seafood is being sourced and address key IUU risks within their supply chains. “We believe this kind of private sector engagement can lead to change on the water, at scale, in reducing IUU fishing,” she said. (https://www.eastwestcenter.org)