By John Anthony S. Estolloso

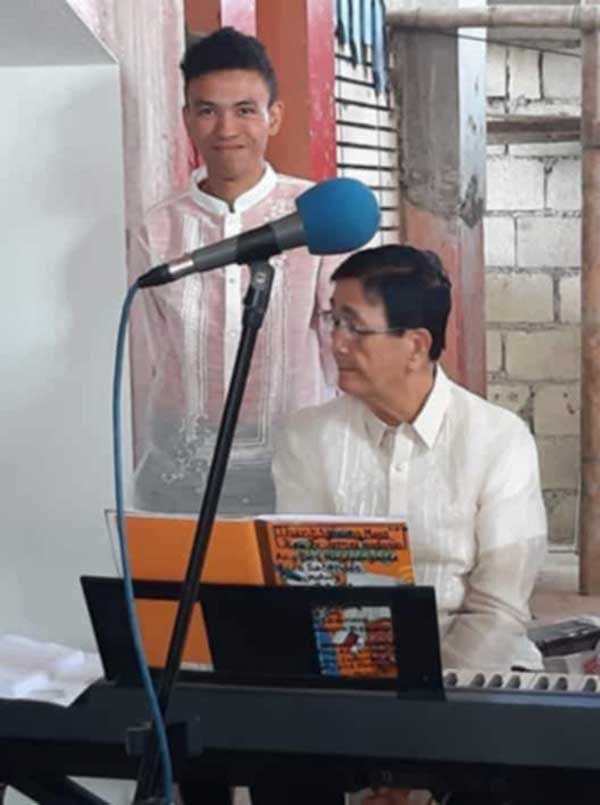

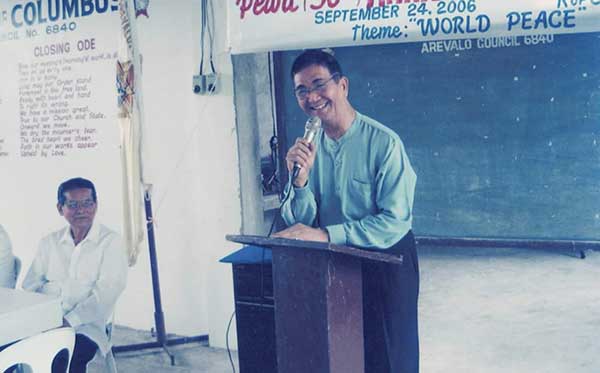

OCTOBER 5 of each year celebrates the teaching profession, with all its qualities and quandaries. And for most of us, there will always be that one mentor figure who has made a lasting impression on our lives. For this writer, that would Mr. Marciano Guanco, pianist extraordinaire and pedagogue of the arts.

He passed away last 2022, a great loss to the young musicians who valued his musical coaching. While his peers and contemporaries from Arevalo knew him as the parish’s choirmaster who led singers to glorious performances in high masses or as the austere catechist wont to insert religious instruction amid the secularity of public schooling, most of his students would remember him as an extraordinarily passionate music teacher.

To clarify, this is neither a belated eulogy nor a biographical attempt of a life devoted to the arts. For all his sophisticated panache, he would have disapproved of it – he would have preferred a well-written critique about which pianist best interpreted Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto.

For that was the stuff of his ‘curriculum’: Mr. Guanco dazzled his students with his virtuosity on the piano and the little bits of art, architecture, ballet, music, theater, film, religion, and history that made existence bearable and that shed light to our humdrum lives. Consider this an anecdotal narrative of a life well-spent with music.

The youngsters who spent many a Saturday thumping out Clementi’s sonatinas or racing through pages and pages of Hanon’s exercises on his piano would recall an endearingly gruff man who would point out garbled passages or haphazardly played scales. Punctuated with sharp exclamations and affirmative grunts, Mr. Guanco would sing out loud the phrase in question while tapping lightly a pencil at your back to keep time.

If this will not suffice to hone the performance of the piece, he would take the erring pianist further into the artform: from his extensive library of musical recordings, he would play sundry interpretations of the composition in question and invite the fledgling musician to listen to the subtle nuances of each performer, pointing out the differences in tempo, phrasing, and accents. In the process, one develops a refined ear for interpretation even as one becomes acquainted with the great names associated with the piano: Gould, Horowitz, Kissin, Cliburn, Licad, among others.

But he goes even further to augment the instruction. Truly yours once had to plow through a waltz of some obscure composer – and I cannot seem to get the phrasing correctly. Undoubtedly, my mechanical playing was insufferable to his ears and try as I might, I cannot make heads or tails on how he wanted me to play the passage. After an awkwardly reflective pause, he pulled out a volume of Impressionist art, then opened it to a page with a landscape brimming with matted colors: pastel blues and greens coalescing into soft yellows and pinks.

‘These painters were the composer’s peers – the artworks and the music were contemporaneous. Play the music with the same colors as the paintings. I want to sense them in your playing: delicate and dulcet. You play the notes too red when they ought to sound pink,’ he extemporized.

Right there and then, there was a personal epiphany of the universality of knowledge and the ever-continuing narrative that strings all of them along, century after century of human achievement, failure, and conflict, all contributary to our understanding of aesthetics. Lesson learned: the arts mirror the times. And they ought to.

Eventually, all’s well that ends well: I was able to play that composition – with the right nuances. Also, I was not surprised that I eventually ended up as an arts appreciation teacher in senior high. For whatever depth and scope I have in the subjects I teach, I owe that immensely to Mr. Guanco’s passion for the arts and his dedication to music education.

While there are teachers who can coach singers and musician well, or write and recite poetry eloquently, or interpret artworks with aesthetic acuity, he was all of them: Mr. Guanco the renaissance man. For him, it was not enough to know the notes or to memorize the names of those dead composers; no, they must become living personages who speak through the music of the performer or the words of the critic – and that humanity trickled down to his students.

He may no longer be around to pass on his aesthetic wisdom to the younger set, but he left us with a palpable appreciation of the Good and the Beautiful, with a profundity that is rarely seen or felt from teachers today. He was impeccably peerless indeed.

[The writer is the subject area coordinator for Social Studies in one of the private schools in the city. The photos are from Niña Guanco and are used with permission.]