By John Anthony S. Estolloso

OUR AFFAIR with clericalism is a Janus-faced conversation: while the country proudly professes to be a predominantly Catholic country, we likewise cast a dodgy side-eye at the frailocracy of the past, something that has waned with the secularization of the clergy. Though contemporary religiosity among Filipinos seems to be felt in varying degrees, our textbooks on history cannot easily detach itself from the narrative that characterized the abusive fraile.

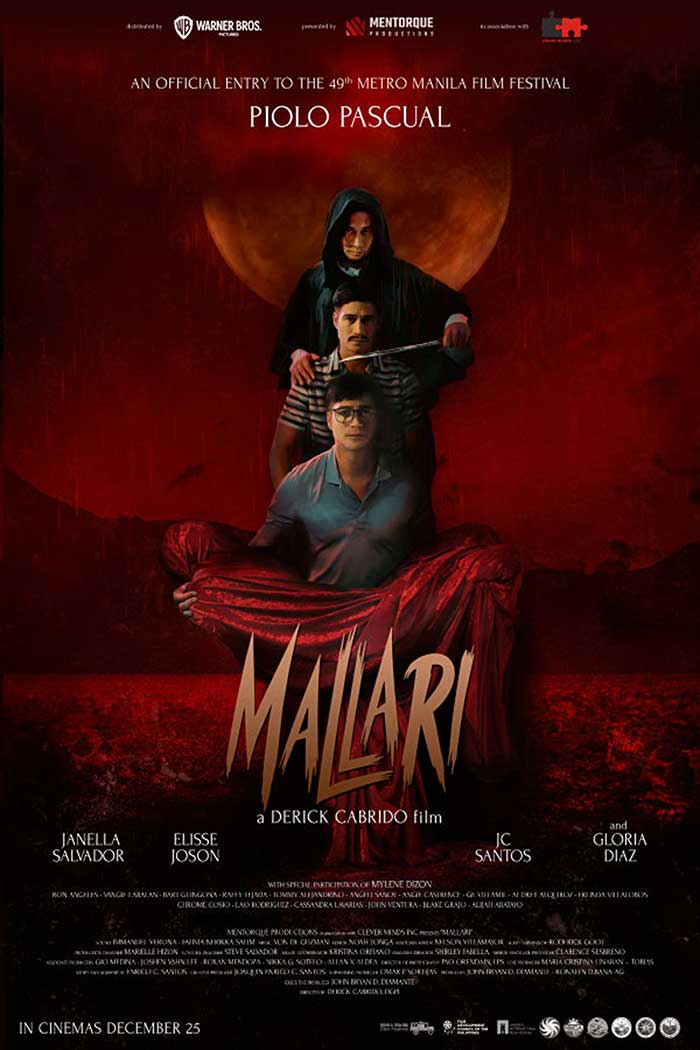

This year’s MMFF returned the spotlight to the conflicted character of the cleric and for whatever stormy relationship we Filipinos have had in the past with people of the cloth, a cinematic retelling of their stories always makes for a good conversation piece. Gomburza and Mallari may resonate with much of what the texts in our social studies classes talked about but to what extent will these provoke the viewer to revisit the literature?

For one, Gomburza serves more as historiographic commentary rather than a biopic. While it courses through segments of the lives of the three priests, the storytelling does not aim to present three separate lives or whatever personal advocacies attached to them; rather, the film underlines the surrounding circumstances that brought the three priests together, from the gambling table to the scaffold. Dali-inspired panoramas at the prologue paired with vignettes of nationalist imagery at the end serve to emphasize this tone of being part of the ’nation’s story’ – or would this further suggest an ongoing search for our collective identity?

What was truly astounding about Gomburza was how the filmmakers managed to expand a single chapter of Nick Joaquin’s A Question of Heroes into a two-hour bio-narrative of heroic proportions. Much of what was lost in our textbooks was revitalized in the cinematic narration: Joaquin’s skeptical question of ‘how “Filipino” was Burgos’ resurfaced and it is fair to say that Cedrick Juan’s fiery performance of the priest as reformer is suggestive of a response. We can empathize with Enchong Dee’s pathos as Zamora, deadpan at the face of impending death, or Dante Rivero’s prosaic yet grounded Gomez, providing a steady voice in the wilderness of reform and revolution. That the influence of an intelligent cleric is far-reaching can easily be discerned in Felipe Buencamino and Paciano Mercado, forerunners of the modern-day student activist – and who can dismiss the gravitas of little Rizal witnessing the twitching bodies at the garrote?

While Gomburza examines the question of national identity, Mallari attempts to frame what justifies that question: what matters the idealism of patriots to the voiceless peasant chained to land and landlord? Essentially historical fiction veiled thinly as a horror flick, Mallari deliberately navigates through entanglements of Catholic customs, folk religion and medicine, modern science, and the machinations that turn the clash of these ideas into projections of protest and insurrection.

Central to the film is Fr. Juan Mallari, believed to have been a serial killer priest with 57 murders to his name. As the film unfolds, the focus drifts from the eponymous character to the circumstances that surround him, weaving a sordid spectacle that takes the viewer through the old ways and rituals that predated and survived the Spanish conquistadors. Mallari becomes a commentary of the Filipino from the grassroots insisting on his identity. Folk religion and medicine as statements of revolution – the ritualistic semiotics that regenerates bertud and aswang – are transformed into ceremonials of struggle against the ruling classes.

Piolo Pascual in three roles seemed a tad too stretched in range and characterization; we can excuse the time-traveling in the commendable attempt to ensure coherence throughout the story. Stealing the limelight with his rather restrained performance was JC Santos, who quietly plods on with his character through most of the film, only to reveal the dark secret of his ancestry at the end. Suffice it to say that much of the acting from the other performers pale in the intensity of the storytelling.

For whatever acclaim both Gomburza and Mallari earns from the Filipino public, one thing is quite clear: cinema provides a fresh veneer to history and its historiographic reading. Then again, the purpose of any film is not to historicize nor to provide an alternative to books of history but to present an understanding of history as seen through the lens of a discerning filmmaker: one can easily end up with concoctions of propaganda – as a certain director did in the recent years – or create a well-referenced and nuanced narrative that captures the collective national sentiment of historical consciousness.

All in all, the priestly stories ‘make sense’. Vilify or acclaim him, the padre has endeared himself to the indio: check out the films for corroboration.

[The writer is the subject area coordinator for Social Studies in one of the private schools in the city.]