By John Anthony S. Estolloso

TO CALL something or someone as balanságon is to describe them as praiseworthy, laudable, or commendable. While the root word (bánsag) would primarily refer to a nickname, it also holds undertones of homage or acclamation: an additional sobriquet to exalt personages, deeds, or accomplishments.

What better word to describe the masterpieces of our National Artists?

Hidden at the second floor of the Hanas Changing Exhibition Galley of the University of the Philippines – Visayas’ Museum of Art and Cultural Heritage are a selection of these artworks, representative of a much more extensive visual repertoire by our National Artists. Aptly entitled Balansagon, the exhibit gives the viewer an eclectic miscellany of Filipino art and the worldviews and lived experiences which continually influence the aesthetic creations of our artists.

While the collection is sparse – at most, three to four works per artist – it nonetheless presents a compelling commentary of Philippine art through the recent decades. Granted, there is little of the classical in the exhibit: an Amorsolo illustration from an American-published grade school reader and some sketched portraits by Joya. One often wonders how Filipino art has fared through the waves of modernism and other avant-garde trends at the turn of the century; the exhibit gives a comprehensive response to that inquiry.

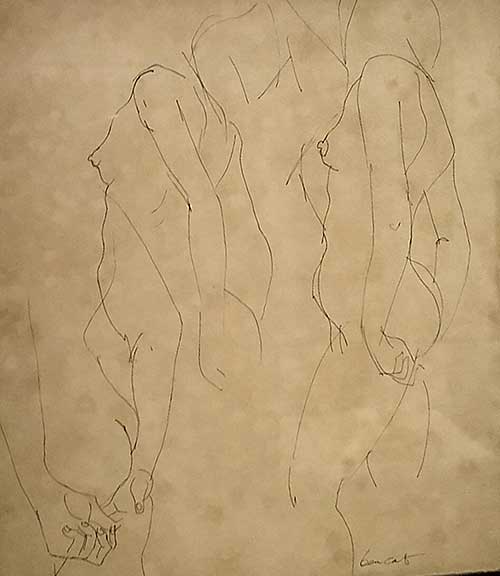

Stylized abstraction seems to take preeminence among the works of our National Artists – and the variety of interpretation shows. For instance, Jose Joya’s juxtapositions and pastiches of hues and shades seem like blots of pensive whimsy when placed alongside Arturo Luz’s austere figurations of geometrical minimalism composed of blunt lines and contrasting dark and light spaces. The cubist tendencies of Federico Aguilar Alcuaz’s works evoke a severely Mondrianesque tang beside the softer color contrasts of Cesar Legaspi’s inchoately hazy human forms.

Figurative distortion appears to be a common thread weaving through the abstractions. Characteristic of his style, Ang Kiukok’s animals project serrated and sharply colored representations of fish and fowl reminiscent of the usual fare of Filipinos. Carlos Botong Francisco’s cartooned peasants in ink on paper set the pastoral quality of the harana through the mundaneness of its medium. Ben Cab’s sketches of the naked human form further denudes his figures to stark carnality by the sinuous curves of his simple lines. Albeit the variety of styles, the modern insists on the final word: while abstraction obfuscates, it likewise clarifies.

In the middle of these paintings and sketches stands the lone statuette of a naked maiden, burdened by a netful of fish: she is Diwata and her full-sized statuary stands at the university’s Miagao campus. Surrounding her sylvan figure are carved wooden panels hanging by the walls and dividers of the gallery, each one etched with stylized figures and inscriptions recalling myths, narratives, and archetypes. With his works, sculptor Napoleon Abueva elevates the purely visual to something concrete (not literally) and palpable, giving physical structure to our aesthetics while situating these on public spaces where painting or poetry cannot easily thrive.

* * * * *

As if to shrewdly complement the modernity of the display, there hang on the main performance hall of the museum the canvases of Juan Luna, Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, Fernando Amorsolo, and Juan Arellano, waiting out the final days of their exhibition. They come from a different time and worldview, from a period where the veracity of scenes and objects must find its way to the canvas via the artist’s eyes and brush.

But the Filipino artist had to come to terms with the ebb and flow of time and tide. More than just capturing the individuality of expressions and intuitions, the works of our National Artists give us a glimpse of our Becoming: that is, to paint – and perhaps to sculpt – a nation and to provide it with a visual benchmark of what has been accomplished by collective struggles, what continues to be created through the contemporary spirit (zeitgeist) of the State, and what we aspire and look forward to in defining our national identity.

Check out the collection: you just might find something about the best of being Filipino in the frames and figures. Balanságon gíd!

[The writer is the subject area coordinator for Social Studies in one of the private schools in the city.]