Since the Philippine government taxes resident citizens on worldwide income, the BIR should be investigating if Tugade’s British Virgin Islands firm has undeclared earnings, says a former finance undersecretary

By Elyssa Lopez, Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

(In collaboration with Rappler and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists)

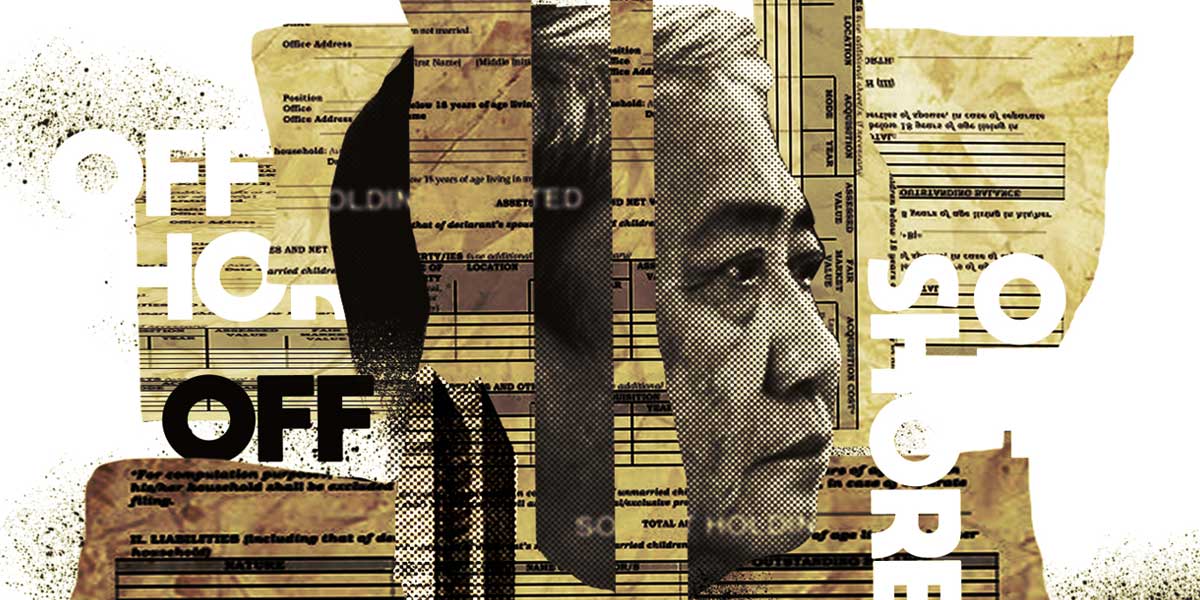

Transportation Secretary Arthur “Art” Tugade has been keeping an offshore company while he occupied government posts in the last eight years, but didn’t declare it in his list of businesses, as required of public officials.

Documents leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed that Tugade has been listed as a director of Solart Holdings Limited, a British Virgin Islands-based firm, at least since 2007.

Based on the Pandora Papers – the latest and largest leak on the offshore holdings of the world’s wealthiest politicians and businessmen – “Solart” appears to be a combination of the first names of Tugade and his wife, Maria Soledad. His three adult children – Jose Arturo, Paul Louie, and Finina Marie – sit as co-directors.

Tugade first held public office as president of Clark Development Corp. under the Aquino administration in 2012. He quit the Aquino government in 2016 to help the presidential campaign of his law school classmate, Rodrigo Duterte, and eventually became one of the first ones to be named to Duterte’s Cabinet, as transportation secretary.

Tugade has not declared Solart Holdings Limited as a business interest in any of the Statements of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) he has filed since becoming a public official.

He has disclosed “offshore investments” worth P57 million as assets every year since 2012, but no details about these investments have been declared, except these were acquired in 2003.

“When you say ‘offshore investment,’ that can mean cash deposits in banks [outside of the country] or shares of companies abroad. If it’s the former, then he has properly disclosed his assets, but if [it is supposed to mean he has an offshore company], then his SALNs are lacking,” former Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) chief Kim Henares said.

PCIJ sent an interview request to Tugade, which outlined questions regarding the information found in the leak. We sent the letter on Sept. 15 and made subsequent follow-ups. Neither he nor his staff has responded to our questions as of posting time.

PCIJ has also reached out to the CSC and the BIR on the legal and tax implications of Tugade’s company in the British Virgin Islands (BVI). They have not responded to our questions as of posting time.

Under the Constitution and the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, the failure of government officials to declare their assets, including business interests and financial connections, is an administrative and criminal offense.

Guidelines by the Civil Service Commission (CSC) specify that officials disclose their connections to any business enterprise, whether as proprietor, investor, shareholder, officer, managing director, and the like.

Under Republic Act 6713, also known as the SALN Law, they are required to divest their business interests to anyone other than immediate family members once conflict of interest arises.

PANDORA PAPERS: 900 PH-BASED INDIVIDUALS

Tugade is one of the more than 900 Philippine-based individuals in the Pandora Papers, a collection of more than 11.9 million files leaked from 14 offshore finance providers.

The investigation, led by the ICIJ, uncovered the offshore companies of some of the world’s richest and most powerful. (Read more about the Filipinos found in Pandora Papers here.)

To cull the documents relevant to the Philippines, PCIJ and Rappler cross-checked the names in the Pandora Papers against lists of incumbent and former public officials, influential businessmen, top taxpayers, and political donors. Tugade is among the 39 politically exposed Filipino personalities found in the leak.

“Arthur P. Tugade” appears in Trident Trust Group records as the beneficial owner of Solart Holdings Limited. Trident Trust, one of the 14 offshore service providers in the Pandora Papers, is the registered agent of Solart Holdings.

In a Trident Trust document, Tugade and his children stated that Solart was expected to have assets worth US$1.5 million (P75 million) in the form of cash, bonds, and securities from the business income of private corporations under the “Perry’s Group of Companies.”

In an interview published in the Daily Tribune in 2019, Tugade said the group was named in honor of his late son Mark Perry, whose death at a young age due to asthma inspired Tugade to succeed in business.

Based on the SALNs submitted by Tugade since 2016, he is a majority shareholder in 10 companies. Seven of these 10 firms are subsidiaries of Perry’s Holdings Corp., according to financial statements submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Perry’s Holdings has interests in logistics, merchandising, agribusiness and fuel distribution. Its accumulated profits and losses, or retained earnings, reached P159 million in 2019.

ICIJ and PCIJ got in touch with Trident Trust to ask why Tugade chose to incorporate Solart Holdings in the BVI as well as the purpose of the entity, but the company declined to share details.

“Trident does not discuss its clients with the media,” a spokesperson said.

Offshore accounts have long been used to hide an individual’s wealth abroad. The prime minister of Iceland, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, for example, resigned after it was revealed that he had kept an offshore account with his wife in 2016, when the Panama Papers were published.

The late dictator Ferdinand Marcos was also found to have kept millions in Swiss accounts after he was ejected from office, with his wife Imelda and four children named as beneficiaries.

In Tugade’s case, it’s a red flag.

“The first question to ask is: Why are you keeping your money in a place known to be a tax haven? And, in his case, why did he not declare this asset in his SALN? With that, he can already be investigated for possible tax evasion,” former finance undersecretary Milwida Guevara said.

Since the Philippine government taxes resident citizens on worldwide income, the BIR should be investigating if Tugade’s BVI firm has undeclared earnings, she said.

The Tugades might also be trying to avoid paying hefty estate taxes in the future, Henares said. Under Philippine law, heirs of a deceased individual’s properties must pay 6% of the value of the net estate. BVI laws do not require beneficiaries to pay estate or inheritance taxes.

Some companies set up in the BVI allow assets to be automatically transferred to co-beneficiaries when one of the members dies. In the case of the Tugades, they own Solart “in joint tenancy with rights of survivorship.” This means members do not individually own any asset in the company, as they are all entitled to the assets as a whole. When a beneficiary passes, his or her rights to the company are automatically transferred to the other members.

“Usually, wealth managers in private banks would advise [their clients] to set up these [offshore companies] so that instead of using a certain individual’s name to purchase securities abroad, for example, they may use this company instead,” the former tax chief said. “They may not also want people [in the Philippines] to know how much money they have…for security purposes.”

RESTORATION OF OFFSHORE COMPANY

While Solart has operated at least since 2007, records showed that Tugade and his children sought the “restoration” of the offshore company in March 2019, after failing to submit due diligence requirements in 2017. Some of the documents requested from Tugade and his family were Solart’s certificate of incorporation and memorandum and articles of association.

It is unknown whether Tugade and family submitted the documents. Records revealed, however, that Solart was fully restored by 2019 after Tugade’s camp submitted a letter from a local bank official vouching for his and his three children’s good standing. A 2016 document stated that the offshore firm was under an “eligible introducer” relationship.

Individuals who want to set up an offshore entity in the BVI are usually required to submit due diligence documents so agents can be assured that the applicant has legitimate business. An agent can forgo this process if an “eligible introducer,” usually a financial institution, can vouch for the individual’s business dealings, as the institution is expected to have already conducted due diligence.

This is not the first time Filipino public officials were found to have kept offshore companies in tax havens. In the “Offshore Leaks” in 2013, now-Senator Imee Marcos was found to have been the beneficiary of Sintra Trust, formed in the BVI in 2002. Former senators Manuel “Manny” Villar Jr. and Joseph Victor “JV” Ejercito were also revealed to have been beneficiaries of companies incorporated in the BVI.

Marcos, Villar, and Ejercito did not disclose these companies as business interests in their SALNs.

These were only some of the reported 130,000 offshore account holders in Offshore Leaks, a watershed moment that forced the United Kingdom, which governs the BVI, to implement a transparency law in the territory and 13 others where the Union Jack is raised. One of the most important provisions of the law is the mandate for each territory to put up a public database of all offshore accounts and their respective beneficiaries.

THE POWER OF SALNs

While a few reforms have been made in the BVI, Philippine officials exposed as having secret offshore accounts were never investigated, much less penalized, in a country where problems with the SALNs can cost the careers of public servants.

In 2012, the Senate, acting as an impeachment court, removed Chief Justice Renato Corona for his failure to disclose the total amounts of his peso and dollar accounts, at P80 million and US$2.4 million, respectively.

Six years later, the appointment of Corona’s successor, Maria Lourdes Sereno, was voided by the high court under an unprecedented quo warranto ruling. The grounds: some of her SALNs before she became chief justice were missing. Sereno was a professor at the University of the Philippines for 17 years prior to her stint in the Supreme Court.

Even low-level officials in government have suffered the consequences of unexplained wealth. In early 2021, the Department of Finance (DOF) launched an online complaints portal so whistleblowers could share information about the unreported wealth of the officers of its attached agencies, like the Bureau of Customs and the Bureau of International Revenue. The DOF said it had investigated 403 officials, 14 of which had been dismissed from service.

Advocates of good governance stressed the importance of making SALNs publicly available to keep corruption in check.

“The [law governing] SALN itself is explicit enough. It’s the compliance [of officials] and proper implementation of [regulators] that is lacking,” freedom of information advocate Jenina Joy Chavez said in an interview.

The Ombudsman recently issued a memorandum restricting access to SALNs. Access is granted only if the requester is:

-the official who filed the SALN;

-acting on a court order in relation to a pending case; or

-an employee of the Office of the Ombudsman’s Field Investigation Office conducting a fact-finding investigation.

As a result, President Rodrigo Duterte’s SALNs from 2018 to 2020 have been kept from the public for the last three years.

Out of six custodians of SALNs, only the Office of the President and the Civil Service Commission (CSC) have continued to release the SALNs of Cabinet secretaries and other government officials.

“When there are [issues on corruption in public officials], the Ombudsman should be one of the first agencies the public can count on [to investigate]…. That’s why it’s unfortunate they are now [the source] of [this problem],” Chavez added.

“SALNs are benchmark documents to check if our public officials are model citizens [who can answer questions like]: Are they who they say they are? Are they spending money that can be explained? In terms of finances, the public demands that people in government can be trusted,” Chavez said.

Public officials, especially those in higher posts, are prone to conflicts of interest once they get involved in important government transactions. Disclosing their business interests is paramount to maintaining the integrity of their positions.

For Right to Know Coalition co-convenor Eirene Aguila, Tugade’s mere disclosure of “offshore investments” in his SALNs was “meaningless.”

“It is a vague declaration, and SALNs are supposed to show where our public officials’ wealth comes from. By declaring the offshore company, we can get a better understanding of his background. But, by omitting that, we keep guessing [what his offshore investments are], and that does not inspire trust,” she added.

Chavez, who is also part of the Right-to-Know Coalition, pointed out that public officials, especially those in higher ranks, get access to the decision-making process of the government.

“You can even be part of the decision, you can influence the decision, or you may also know someone in the government who can be part of or influence that decision,” she said.

DUTERTE’S SENATORIAL BET

After winning the 2016 elections, President Rodrigo Duterte, within five minutes of his first press conference as president-elect, named Tugade to his Cabinet.

“My classmate in law school, our valedictorian, Art Tugade, will get [the] DOTr (Department of Transportation) [Secretary post],” President Duterte said. “He’s good…. [When we were still studying in law school] he was already a big guy.”

In July, during his weekly national address, Duterte urged Tugade to run for senator. The transportation chief has not officially announced his plans for the upcoming elections. However, in August, the Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban), the President’s party, included Tugade in its initial list of candidates for senator in the May 2022 elections. END

Contributors to the ‘Pandora Papers’ Project: Carmela Fonbuena, Miriam Grace A. Go, Karol Ilagan, Elyssa Lopez, Pauline Macaraeg, Ralf Rivas, Felipe Salvosa

Tugade Illustration: Luigi Almuena