First of two parts

APARRI, CAGAYAN – The fishing season for aramang, a small species of marine shrimp also known as spider shrimp, will open again in the middle of November. Majority of the 11,000 fisherfolk in the small town of Aparri in the northern tip of the Philippines — near Taiwan — catch it for livelihood.

It’s a popular export to neighboring countries like China and Japan. However, an unprecedented poor catch of aramang came last year and fisherfolks are afraid it would be repeated because of a new dredging project at the mouth of the Cagayan River, along the western side of the town.

The dredging project is part of the Cagayan River Restoration Program, which aims to rehabilitate the heavily-silted river and prevent flooding. It’s a tripartite agreement between the provincial government’s Inter-Agency Committee (IAC), the Great River North Consortium (GRNC), and Riverfront Construction Inc. (RCI).

The river and the sea were “generous” before the dredging project began, said Edison Palattao, a 49-year-old fisherman in Punta village.

“Marami kaming huli na aramang saka isda [noong] wala pa ‘yung dredging… Noong pumasok na ang mga barko… nagsimula nang humirap ang huli (We caught a lot of aramang and fish before the dredging operations… But when the ships arrived… the catch started to decline,” Palattao said.

“Noong open season na namin ng aramang noong November [2021], kasagsagan na nila mag-operate. Doon na kami, wala na kaming huling aramang (During our open season for aramang last November [2021], they were already operating full-blast. That was when we couldn’t catch aramang anymore),” he said.

A small boat with two to four fishers used to catch more than 200 containers over five days, earning them from P300 to P800 per container, depending on the market price.

Since the dredging project, Palattao said they could only catch five containers worth of aramang on most days. They considered themselves lucky if they got 50 containers and there were a few times when they caught “zero.”

“Ganoon karami ‘yung nawala. Doon na kami nag-umpisang magpulong-pulong, dahil sa wala na kaming huli (That’s how much was lost. That was when we began to meet and discuss, because we weren’t catching anything anymore),” he said.

The scarcity of aramang has driven the price to P1,000 per container but the increase could not compensate for the decline of the volume of their catch.

It was not just the fishermen who suffered from the poor catch, but also thousands of other residents who rely on aramang for livelihood.

“Didigra (Disaster),” said Marlin Bugarin, a 47-year old dried fish vendor, speaking in the local vernacular Ilocano.

Bugarin used to earn at least P8,000 over five days for sun-drying and selling aramang and other obtainable fish. Last year, in December 2021, Bugarin said she earned P695 over five days of work. The following month, in January 2022, she earned P990. In April, she earned P1,100 for drying aramang.

Her earnings were below the minimum daily wage rate of P375 for the agriculture sector in Cagayan, pushing her family further away from the monthly income of P42,000 that a five-member household needed to survive, based on data from the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA).

“Dati-rati kami ang tumatanggi sa dami ng ibibilad; ngayon wala nang ibibilad (Before, we would say no to the huge catch we would need to dry; now we have nothing to dry),” she said.

BFAR, other expert opinions

The open season for harvesting usually runs until the end of August, although the harvest comes to a halt when the weather is bad.

Fisherfolk in Aparri usually fish over five days and then allot a 15-day interval before the next trip to allow other fishing boats to harvest. It’s a schedule that the community has adopted to avoid “too many boat landings on the water.”

This means they can only deploy and harvest twice a month or a maximum of 10 days.

The regional office of the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) confirmed the decrease in aramang catch in Aparri but said it may not necessarily be related to the river dredging activities.

BFAR Regional Director Angel Encarnacion was quoted in a newspaper report saying the decline in harvest may also be attributed to the limited movement of fishers during the pandemic lockdowns, catchability of the gears, sudden changes in the weather, overfishing, and increase in boat landings especially after commercial fishers converted to smaller boats to be able to catch inside municipal waters.

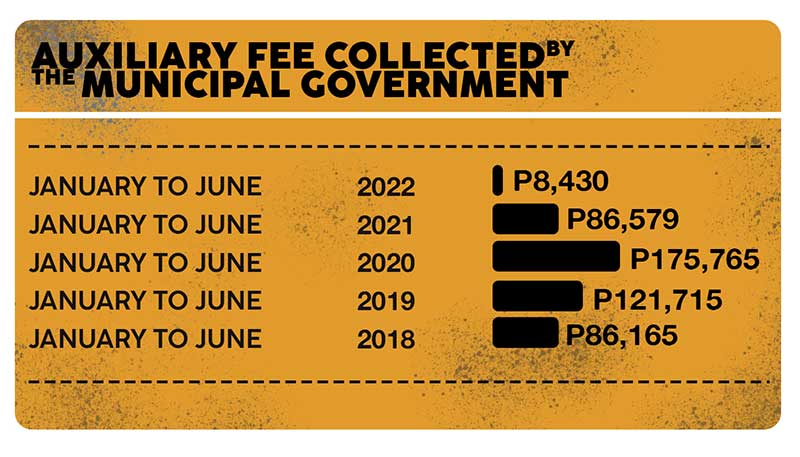

PCIJ tried but could not get data on the total fish catch in Aparri before and after the dredging activities started, but the steep dive in the municipal government’s collection of “auxiliary fee” for aramang shipped out of town was telling.

The volume of aramang shipped out of Aparri decreased more than 50% in the first year of the pandemic, when strict lockdowns were imposed. But the decline grew to more than 90% after the dredging project was launched in 2021, even as lockdowns relaxed and fishermen were already given exemptions.

The local government collects P10 from traders for every sack of dried aramang shipped out of the town. Data in the first half of 2022 shows that the lowest monthly collection was P180 in February, equivalent to only 18 sacks of dried aramang.

Other experts interviewed by PCIJ said the extraction activities in Cagayan River and Babuyan Channel do pose threats to marine biodiversity and the livelihood of the fishing community in Aparri.

Diovanie De Jesus, campaign and science specialist of Oceana Philippines, said extraction of sediments causes “high sedimentation” and “turbidity,” which “affect not only the water but the microorganisms.”

De Jesus said high turbidity — the murkiness of the water due to suspended particulates — affects the plankton or the diverse collection of organisms found in water that are unable to propel themselves against a current.

These impacts on marine biodiversity of the extraction activity are no secret. The Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) submitted by the project proponent even noted that “dredging, although temporary in nature, may cause re-suspension of silt that will enhance turbidity of the water.”

“Such conditions will potentially impact aquatic organisms such as eels and aramang,” the EIS read.

The EIS further stated: “Immediate impacts of increased suspension of sediments during dredging activities – low dissolved oxygen and decreased light penetration – will adversely impact life-history stages, e.g., eggs, juveniles, and adults, of many estuarine organisms.”

RCI, one of the two contractors in the dredging project, acknowledged that dredging may temporarily affect the water’s turbidity as its processes may result in the resuspension of mud that may naturally have an effect on organisms.

But this consequence, it said, will be counterbalanced by the removal of silt and deepening of the river – which may even result in long-term benefits that include a wider area for spawning and nursery ground for organisms.

RCI also said it has yet to perform a full dredging operation, noting that “it is in our opinion that our initial operations have not yet impacted the fish catch of the fisher folks.”

Disturbing the food chain

Marine biologist Vincent Hilomen said the dredging activities could have disturbed the food chain and adversely altered the source of energy for the growth and reproduction of aramang.

He explained how materials contain “interstitial pieces that are habitats of microorganisms” and that that these organisms are “prey or food item to a little bigger animal and that a little bigger animal will be again the food of the aramang” or other species.

“So if they remove the base of the food chain that small species eat, the aramang are deprived of their food. And it’s a reason why during that season they observed 95 percent decline in their catch,” said Hilomen.

Hilomen said dredging “destroys marine organisms, habitats, and ecosystems,” noting that it deeply affects the composition of biodiversity, which leads to “a net decline in faunal biomass and abundance or a shift in species composition.”

Particles from sand material that are too fine become vast dust plumes, changing water turbidity, and resulting in major changes to aquatic habitats over large areas.

Fisheries and aquaculture expert Antonio Liquigan, a retired professor at the Cagayan State University, said the moment someone dredges the bottom of the river, sulfur dioxide, an odorous by-product of composting plants or animals trapped in sand materials, is released.

He said when sulfur dioxide is released from the sediment, and with the presence of hydrogen ions as well as oxygen, it becomes sulfuric acid that could kill the fish.

Liquigan, a resident of Punta village in Aparri, said another reason why the fish and aramang are depleted is because of the “vibration and loud sound” created by dredging activity.

“Fish are very sensitive,” he said, adding that marine species tend to move away from a disruptive activity.

Aparri LGU and community not properly consulted

The EIS is part of the Philippine Environmental Impact Statement System (PEISS) that environmentally critical projects like that in Aparri must go through. An Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) is required to predict and evaluate the likely impacts of a project in addition to setting preventive, mitigating, and enhancement measures to protect the environment and community welfare.

Public involvement is supposed to be incorporated throughout the entire process of the EIA. But the fisherfolk and the local government of Aparri belied claims from the provincial government that proper consultations were done.

Ricardo Umoso, president of Aparri Federation of Aramang Fisherfolk Stakeholders, said there was no proper dialogue or formal consultation with the fisherfolk.

“They did not present anything to us during the planning stage of the project,” he said, adding that a social development plan should have been crafted and presented to the people beforehand because “these government agencies already knew the potential impacts of this dredging operation.”

Lawyer Jane Tadili, Aparri’s municipal administrator, also said on many occasions that the river restoration project was introduced and implemented without prior coordination with the local government.

“Wala kaming alam tungkol sa project. Bigla na lang silang dumating dito na approved na pala at hindi man lamang tinanong ang mga taga-Aparri kung gusto namin ‘yung project. Wala din kaming hawak na kahit anong papers tungkol sa project. Kahit project details and ‘yung mga MOAs [memoranda of agreement], wala kaming copies (We know nothing about the project.

They just came in with the project already approved. Aparri residents were even not asked if they support the project. We don’t even have copies of the project details or the MOAs),” she said.

The environment department and the provincial government have not issued clear guidelines on how to address loss and damages that will occur during the implementation of the project, she said, noting that agencies like the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) started visiting the community only after several complaints have been filed against the dredging operations.

Cagayan Province Gov. Manuel Mamba told PCIJ in an interview in November 2021 that the provincial government and other concerned government agencies had consulted the Aparri local government before implementing the project.

It’s a position echoed by DENR Region II Director Gwendolyn Bambalan. She said “every process, including public scoping and consultations, was done before the issuance of any permit.”

A Facebook post by the Cagayan Provincial Information Office dated April 26, 2021 shows a ship inspection conducted before the start of the project. Led by members of the IAC and attended by government officials and supposed stakeholders, the inspection was done to prove that no black sand mining was being done.

But Father Manuel Catral, parish priest of San Pedro Telmo Catholic Church and lead convenor of Cagayan Advocates for the Integrity of Creation, said the community was not part of those supposed consultations.

“Presenting the project to a few selected people is not considered public consultation. There was no fisherfolk organization that was consulted,” he said. END

Photographs by Mark Z. Saludes

Additional research by Elyssa Lopez