By Claire Gagne

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a major impact on people around the world and the key to getting back to something that looks like normalcy—and reducing severe illness and death—is reaching herd immunity to Covid-19.

Herd immunity is the point at which enough people have enough immunity to a disease that it can no longer spread easily, says Julie Swann, head of the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering at North Carolina State University, who is an expert in vaccine distribution.

People can get this immunity either by getting sick with a given virus or bacteria, or by getting a vaccine against the disease.

Because getting sick with a disease can be potentially life-threatening, vaccination—considered to be one of the greatest scientific breakthroughs of all time—is generally considered the best and safest way to become immune.

When a high number of people are vaccinated, it becomes more difficult to transmit viruses or bacteria to others because the germs keep meeting people who are protected against infection.

What’s more, herd immunity protects vulnerable people in the community—people with health conditions or those who are too old or too young to get vaccinated—from getting sick.

“You’re both protecting a major vector that is spreading the pathogen, and you’re making it difficult for the virus or bacteria to get a foothold because there are not enough susceptible people in the community,” says Pedro Piedra, MD, professor of molecular virology and microbiology and of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

The good news is that every day more people are vaccinated against Covid-19, bringing us one step closer to herd immunity.

EXAMPLES OF HERD IMMUNITY

There are many diseases we are protected against because of herd immunity.

Dr. Piedra points to vaccination against Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib), a type of bacteria that causes meningitis in young children, as another example of a disease suppressed through herd immunity.

“By vaccinating children against that disease, we have been able to basically eradicate it,” he says.

But herd immunity isn’t a one-and-done deal. “There are plenty of examples of herd protection,” Dr. Piedra says, “but the minute that you loosen up or decrease vaccine coverage, there is the potential for outbreaks to occur.”

Take measles, for example.

The illness was eliminated from the United States in the year 2000, thanks to high vaccination rates against the disease. In recent years, however, there have been outbreaks of measles because it’s been introduced, usually by a traveler, and then spread in areas where people didn’t receive their recommended vaccinations.

How were those measles outbreaks controlled? Through herd immunity. Boosting measles vaccination rates in areas with unvaccinated children and adults helped stop the spread, says Swann.

HERD IMMUNITY AND COVID-19

Typically, you need a fairly high vaccination rate to achieve herd immunity, and Covid-19 is no exception.

While it’s too soon to say exactly what percentage of people need to have immunity, either from getting the disease or from a vaccine, the World Health Organization says the number is “substantial.”

Dr. Piedra estimates it to be higher than 80 to 85 percent of the population.

Some people, including politicians, have suggested that we should let the virus run its course through communities and gain immunity that way. The proposal boils down to letting the virus infect a whole bunch of people so the population at large can reach herd immunity faster.

Both Swann and Dr. Piedra disagree with that approach.

“This really puts many people at huge risk,” says Dr. Piedra. “If you think about before vaccines became available, that approach is what has caused all the deaths and hospitalizations that have occurred worldwide.”

WHAT’S GETTING IN THE WAY OF HERD IMMUNITY?

There are a number of things that could get in the way of herd immunity for Covid-19, both in the United States and on a global scale.

VACCINE AVAILABILITY

The biggest barrier to herd immunity right now is the availability of vaccines.

“Right now, supply of vaccines is still limited. And if we had more supply, we could be vaccinating more people, both in the United States and worldwide,” says Swann.

VACCINE HESITANCY

Another hurdle when it comes to herd immunity is vaccine hesitancy.

“There are some people who are choosing not to take the vaccine right now,” says Swann.

A recent NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist survey showed 30 percent of American adults did not plan to get the vaccine.

“I think we’re going to end up with communities of people with lower vaccination rates,” says Swann.

KIDS AND VACCINES

Herd immunity requires high numbers of people to be vaccinated, and that includes children, says Dr. Piedra.

Right now, there are no Covid-19 vaccines approved for people under 16 years of age, although studies are underway for younger children.

BARRIERS TO VACCINATION

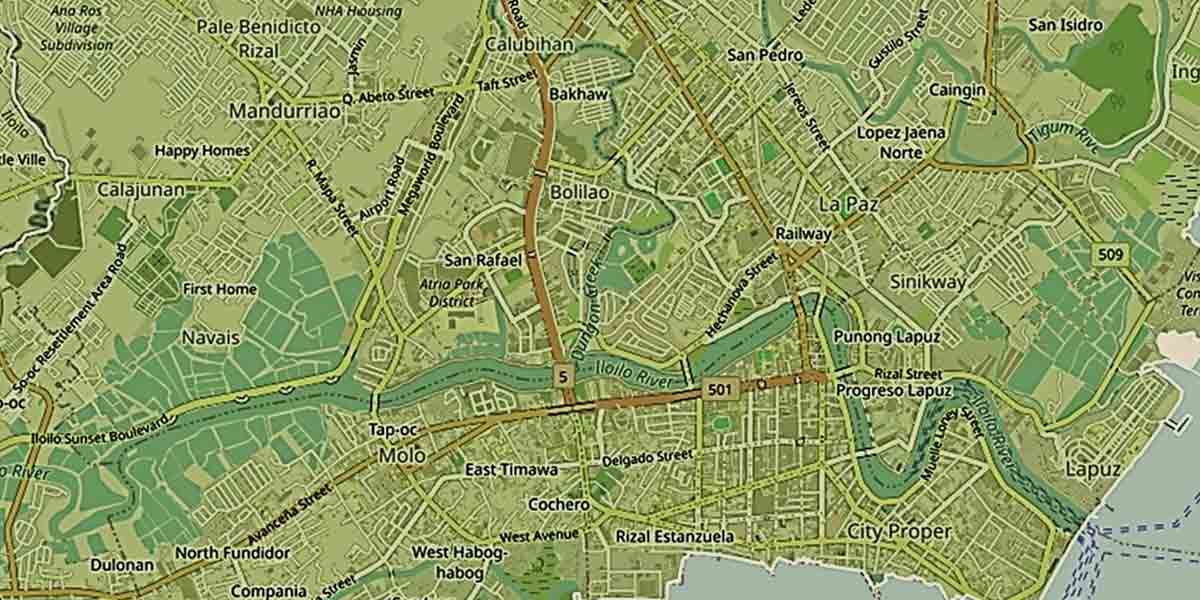

It’s also important to make sure everyone who wants the vaccine is able to get it, says Swann, regardless of whether they live in an urban center or a rural community.

With improved access and availability, more people could be vaccinated and we could reach herd immunity sooner.

Information and support are key to removing barriers and helping people to get the shot, says Dr. Piedra.

For example, a lack of internet access or the ability to navigate appointment-booking sites can be a problem. In addition, mobility or transportation issues can keep people from traveling to vaccination sites.

“We need to be able to reach out to the African American population, the Hispanic population, the different populations that make up our community and ensure that they have the best information and the support, and be able to address their concerns about the vaccines.”

WHEN WILL COVID-19 HERD IMMUNITY BE REACHED?

Both Dr. Piedra and Swann say they expect we’ll see significant protection against Covid-19 in the coming months, reducing hospitalizations and deaths.

What happens next really depends on human behavior and on how the virus mutates.

HUMAN BEHAVIOR AND HERD IMMUNITY

“We do simulation models of what’s going to happen,” says Swann.

In one, the simulation estimated how things would turn out if, at the halfway point of the vaccine rollout, everybody took off their masks and went back to normal.

“You get a huge surge in cases if you do that too early,” she says.

It will be important that people continue with public health measures to reduce the spread—even after they are vaccinated—until there is a higher level of protection. That means wearing masks and social distancing.

GLOBAL IMPACTS OF COVID-19

Another consideration is what’s going on in other countries. While there may be significant protection in places with higher vaccination rates, once people start traveling, or when countries open their borders to other nations, there’s the potential for flare-ups of the disease in communities.

How far those outbreaks spread depends on how many people are vaccinated.

Swann gives the example of a university that opens up for in-class learning this fall.

“Let’s imagine that 70 percent of people are vaccinated and 30 percent are not,” she says. “And now you go back to having people share dorm rooms and having them in classrooms together and eating together. You bring a couple of cases of Covid-19 onto that university campus and it will spread.”

LENGTH OF VACCINE PROTECTION

It’s also still unclear how long you are protected against the virus by either having gotten sick or having gotten the vaccine.

“It’s early right now because you need time to collect those types of data,” says Dr. Piedra. “We know we have protection at least out to six months and probably more.”

That said, there’s a chance protection will wane and you will need another shot at some point down the road, says Swann.

COVID-19 VARIANTS

Another big unknown is how the virus will continue to mutate. So far, the vaccines we have provide at least some protection against the new variants, says Dr. Piedra.

It’s still unclear, though, whether we’ll need regular, and perhaps annual, doses of the Covid-19 vaccine in the future, or if it will need to be tweaked over time to address new variants.

“SARS-CoV-2 [the virus that causes Covid-19] is the new player on the block,” says Dr. Piedra. “We’re going to have to wait to see how it’s going to take its final foothold.”

Both Dr. Piedra and Swann peg Fall 2021 as the point when we’ll see significant protection against Covid-19 and society should largely be able to get back to normal. “But we will still have micro flare-ups, like the embers of a fire,” says Swann. “I think it’s going to take us a while to get to the point where we have zero outbreaks.” (www.thehealthy.com)