By Joseph B.A. Marzan

World Press Freedom Day was conceived by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly on December 20, 1993 after designating May 3 of every year as a day to remind states to respect their commitments to press freedom and for media professionals to reflect on issues of press freedom and professional ethics.

According to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Press Freedom Day is also a “day of support and remembrance for media organizations and practitioners who have been targets of restraint or abolition of press freedom”.

The date traces its origins back to a UNESCO seminar in 1991 in Windhoek, Namibia where African independent journalists signed and adopted the Declaration of Windhoek on Promoting an Independent and Pluralistic African Press, or simply known as the “Windhoek Declaration”.

An extract of the said declaration states that “The establishment, maintenance and fostering of an independent, pluralistic and free press is essential to the development and maintenance of democracy in a nation, and for economic development.”

The theme for this year’s World Press Freedom Day is “Information as a Public Good”, which UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay says, “underlines the indisputable importance of verified and reliable information, and calls attention to the essential role of free and professional journalists in producing and disseminating this information, by tackling misinformation and other harmful content.”

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), signed and adopted by the Philippines in 1948, states that “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”.

Section 4 of Article III of our own 1987 Constitution adopted the UDHR provision, stating that “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

The Supreme Court in the 2008 landmark case of Chavez vs. Gonzales also upheld press freedom, with Chief Justice Renato Puno calling it “crucial and so inextricably woven into the right to free speech and free expression”.

Puno also remarked in the case that freedom of the press “is the instrument by which citizens keep their government informed of their needs, their aspirations and their grievances” and “the sharpest weapon in the fight to keep government responsible and efficient”.

But the Philippines has not been doing so well recently on the press freedom front, ranking 138th in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index of the international organization Reporters Sans Frontières (Reporters without Borders) based in Paris, France.

This continues the country’s slip in the index – 136th in 2020, 134th in 2019, 133rd in 2018, and 127th in 2017.

2020 was momentous for the Philippine press, like every other year in the Duterte administration, with the denial of ABS-CBN’s legislative franchise, the guilty verdict in the cyberlibel case against Rappler and its CEO Maria Ressa, and the arrest of journalist Lady Ann Salem on false firearm charges, just to name a few.

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) also ranked the Philippines third with most journalists killed in 2020, with 3 confirmed deaths.

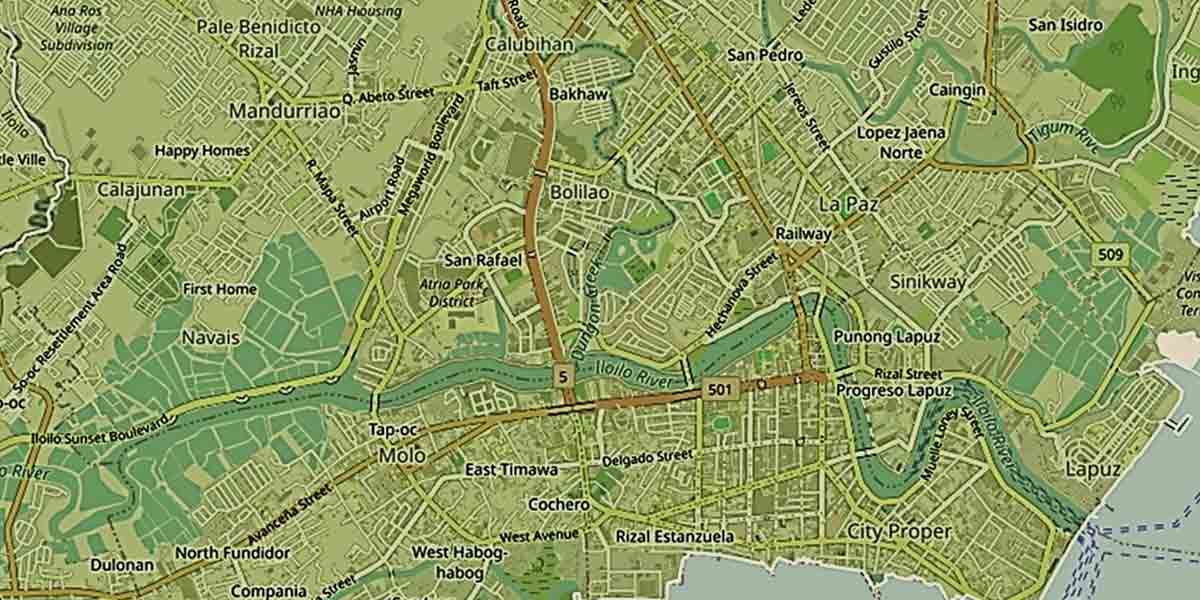

PRESS FREEDOM IN THE LOCAL SETTING

Iloilo and the region are no strangers to threats against press freedom, having had a string of threats and violence in recent time.

Daily Guardian itself was threatened by an ex-politician in Iloilo City after it reported his disbarment due an extra-marital affair, the report of which was based on a decision posted by the Supreme Court in its website.

Philippine Daily Inquirer’s Visayas bureau chief Nestor Burgos was also the subject of “red-tagging” by a self-proclaimed rebel returnee last year, accusing the newsman of being a recruiter for communist rebel groups.

Former broadcast journalist John Heredia was shot dead in Roxas City yesterday, the latest in the string of killings of active and former journalists.

Dr. Zoilo Andrada, a Communications and Media Studies professor at the University of the Philippines Visayas, believes that press freedom has changed since the introduction of modern technology.

“For me as an academician, press freedom is both the marketplace of ideas and watchdog of the government function. It is participatory democracy of self-expression to fight against an abusive governance. The emergence of modern media platforms, however, has changed the journalist’s participatory democratic interaction environment. The strong political and economic affiliations, biased access to news and information, and the overpowering social media use of the 21st century consumer of information put press freedom on the spotlight. This is one pressing challenge among the modern-day journalists to promote objectivity, clarity and credibility in disseminating information,” Andrada told Daily Guardian.

The professor also shared that the public, as media users, may be abusing the concept of press freedom to express their opinions, warning that it must be used cautiously.

“The delusion of the word freedom to media users – that everyone has the right to say or question about anything against anybody on a given situation and platform. To put it bluntly, it an entitlement to one’s opinion. This, however, is not true in every situation. Freedom of speech has limitations. So, people need to be wary about this. Press freedom should be practiced with caution. Wrongfully done, it can create misunderstanding, skepticism, or paranoia among the public,” he said.

As to press freedom in the local setting, he expressed a “crucial need for people to be more responsible and critical media users” due to the rapid spread of misinformation and disinformation on social media platforms.

He cited as an example the case of Patrocenio “Don” Chiyuto in Roxas City, who allegedly convinced people to invest in “double-your-money” schemes.

The alleged abduction of Chiyuto, Andrada said, steered public opinion into supporting him despite his alleged misdeeds.

“There is a divided public opinion, the victim-supporters and the victim-accusers. The no-holds-barred posting of opinions on social media sites failed to control the spread of misinformation and disinformation. The absence of social media post restrictions made this possible. Evidently, posts became too personal, posing a greater challenge to press freedom. It is interesting to note that the social media platform has now become the marketplace of ideas of fake news,” Andrada said.

He added that the press agency, seen as a reliable and credible source of information by the public, was not vulnerable to the “news-demic” brought about by the uncontrollable spread of fake news.

“The belief that journalists are gatekeepers of information starts to blur in this digital age. There is an essential need for deeper understanding of misinformation and disinformation. Simply put, any set of information disseminated and lacked clear evidence, or an expert opinion is misinformation. It is the spread of information that is inaccurate in the guise of being accurate,” he said.

He also called attention to headlines made by news agencies which tend to grab emotion responses from audiences.

“I would like to highlight the role of news agencies as source of news information, particularly online news sites, is alarming. Online news stories have headlines that induce emotional responses from the readers, resulting to the rapid spread of news and making it hard to separate and differentiate between what is real and what is not,” he said.

He shared an activity he conducts with his journalism classes, letting his students read the article “The Silent Partner: News Agencies and 21st Century News” by Jane Johnston and Susan Forde, published in the International Journal of Communication in 2011.

In the article, Johnston and Forde said that there was a need to analyze the media culture that accepts copy from news agencies as “gospel”— a commodity to be used and reused without checking accuracy, and often without attribution.

He said that his students were able to verify that there is indeed inaccuracy of information and biased news writing in its compendium of news articles, and that the copying and pasting of news articles and photos “added anomalies to the spread of disinformation”.

“As a journalism teacher, it is a proper to make my students aware of this malpractice for them to not just be reading and writing news stories, but to become more vigilant, sensitive and critical to information provided by the different media platforms. Students have to be conscious as to how fast fake news spreads which eventually cause more damage than real news. And who is to be blamed for this? People manufacturing fake news makes it more perilous because they are not controlled by the truth. More often than not, they create conditions that catered to unconditional emotional responses from their target readers,” he said.

Andrada surmised that to uphold press freedom “is to be responsible information manufacturers and consumers” and stressed that the public and the media must be media literate.

He added that members of the media profession must practice the basics of news reporting, including fact-checking, telling the truth, and verifying procedures.