By Zo Cabunagan

I don’t know when it slipped into my speech

that soft word meaning, “if God wills it.”

Insha’Allah I will see you next summer.

The baby will come in spring, insha’Allah.

Insha’Allah this year will have enough rain.

………………………………

How lightly we learn to hold hope,

as if it were an animal that could turn around

and bite your hand. And still we carry it

the way a mother would, carefully,

from one day to the next.

— Danusha Laméris, Insha’Allah

In Cebuano, one of the Visayan languages, there is a word that holds an equivalent interpretation, puhun (alternatively spelled puhon), used by native speakers to convey their optimistic perspective toward the future. There is also the Tagalog expression bahala na, described in Sikolohiyang Pilipino as “determination in the face of uncertainty.” The late social psychologist Virgilio Enriquez explained, “It is risk-taking in the face of the proverbial cloud of uncertainty and the possibility of failure. It is also an indication of acceptance of the nature of things, including the inherent limitations of one’s self.” But such acceptance neither corresponds to acquiescence nor passive resignation to circumstances. “It is as if one were being forced by the situation to act within his own capacity to change the present problematic condition. He is required to be resourceful and, most importantly, creative, to improve his situation,” he continued.

Interestingly, it is believed by many that the word bahala emanated from Bathala, the name of the supreme deity who created the universe according to the indigenous religious beliefs of the Tagalog people. This gives bahala na the loose translation of “leave it up to God.”

The 2017 film Gifted included a dialogue between the main protagonists in which Mary, an intellectually gifted seven-year-old, asks her Uncle Frank, “Is there a God?” They go on to engage in a thoughtful conversation, with Frank admitting, “I would if I could, but I don’t know, and neither does anyone else.”

“Roberta knows,” Mary interjects. To which, with quiet wisdom, he responds, “No, she doesn’t. Roberta has faith, which is a great thing to have. But faith is about what you think and feel, not what you know.” The scene ends with Frank suggesting that, regardless of beliefs, everyone will be together again in the end, offering a sense of comfort to Mary.

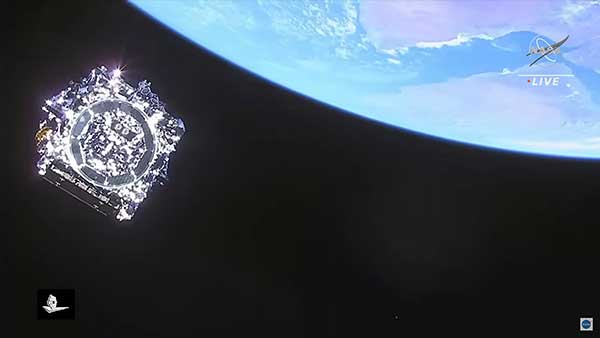

We used to believe that the earth was flat, and then we imagined our world to be the very heart of all that exists. Now, we gaze upon the sun and the solar system, the stars and the galaxies, and all of space and time and everything within it unfolding before us. Every now and then, our history is being rewritten and our understanding of how we came into being and where we are headed becomes renewed.

Science and religion have long coexisted and chronicled to have influenced each other in their shared pursuit of providing answers to the unknown. While each has its own way of dealing with things and addresses different aspects of the human experience, both seek to answer profound questions about existence, purpose, and the nature of reality.

Through observation, experimentation, and the development of theories that can be tested and refined, science helps us understand the “how” of things — how life evolves, how stars are formed, how matter behaves, and how we interact with the world around us. Religion, on the other hand, focuses on the “why” of things — why we are here, why we experience suffering, and what comes after death.

Science deals with the physical world and is always evolving as new discoveries are made. It provides detailed explanations for natural phenomena which can deepen our appreciation for the complexity and beauty of creation, often leading to awe that may strengthen spiritual beliefs.

Meanwhile, religion offers a lens through which scientific discoveries can be interpreted. By addressing the deeper questions of meaning, purpose, morality, and the ultimate cause of existence, it provides a framework for understanding life’s riddles beyond what can be physically measured.

Ultimately, while science and religion have differing ways of seeking truth and understanding, each offers valuable insights into the mysteries of the universe and the human condition.

In a similar fashion, truth and reality can also work together in addressing human curiosity and the unknown. How does one know that something true is also real? And how does one know that something real is also true? To a certain extent, the answer to these questions also answers this question: What is the point of the Dinagyang Festival and all our other religious commemorations?

One manner to acknowledge that query is to look at the definition of a word synonymous with ‘celebration’ — ‘keeping’, or the act of owning, preserving, or safeguarding something. With this understanding, it can be surmised that Dinagyang is one of the ways we uphold and protect what we deem important and true. By having a tangible representation of it—one that can be perceived by our immediate senses—we are able to think and feel that our faith is real.

From another perspective, Dinagyang is more than just a festival or celebration, but a living thread of our cultural identity. What does it truly mean to be an Ilonggo? What makes an Ilonggo an Ilonggo?

Is it the manner in which we prepare and appreciate our food? Is it the affable charm in the inherent cadence of the way we speak? And how do these qualities relate to our individual narratives? What does it mean for the middle-aged farmer from the mountains of Leon, who sets out before dawn to bring his produce to the Iloilo Terminal Market, all so he can send his children to college? For the stevedore at the Iloilo Fastcraft Terminal, who’s saving up for the birth of his child? For the young professional juggling two BPO jobs to help cover a parent’s medical expenses? For the single mother, a private school teacher by day and a TikTok seller by night, striving to make ends meet? For the university freshman, who, after growing up in a rural town, now faces the oftentimes overwhelming pace of city life? Their stories, too, are part of the collective narrative of the Ilonggo people.

Perhaps what it means to be an Ilonggo will remain as elusive as the question of what makes us human. Carpe diem, memento mori, tempus fugit, and the relatively newer expression “you only live once” (YOLO) — equally beautiful messages that may be interpreted in differing ways but nonetheless hold a similar truth: that what matters most is the present moment, and that the journey is more important than the destination. As with emotions, which are meant to be felt and never entirely understood, perhaps meaning is never really meant to be found but lived.

***

We tend to approach art with an analytical and evaluative eye, perhaps in search of the hidden art critic within ourselves—more often than not, to no avail. Art criticism requires the application of established standards, theories, and historical contexts to understand the meaning, technique, and overall quality of an artwork. But this is not the only way in which one can engage with art.

What draws you to the work? Or what do you find intriguing about it? What does it remind you of? How does it make you feel?

Art appreciation invites us to experience art not just with our minds, but with our hearts. It teaches us that in their truest manifestation, the beautiful, the graceful, and the sublime—as with faith, hope, love, among other things that the writer and poet Antoine de Saint-Exupéry might refer to as the “essential”—can only be perceived clearly when we open ourselves to deeper emotional connection.

To be willing to give more of oneself so that one can truly receive. With this understanding, perhaps we can learn to find greater value in art—and in each other. Perhaps, then, we can learn to be kinder to one another, more respectful of each other’s journeys, and more open to listening to others’ stories.

***

Some may see our celebrations as an affirmation of the beliefs they hold dear and the principles they deem important to live by. For others, they serve as a momentary escape from the monotony of daily existence. And for some, they offer an opportunity to gain new experiences, create lasting memories, and establish genuine connections.

In the end, despite all our differences, it’s just one thing we’re truly yearning for: that something, that someplace, or that some time we belong to—and belongs to us. Home.

For Kiara Aleeyah,

One day, you’ll be old enough to understand this. Or maybe not. But it won’t matter.

As you turn a brand-new page in your nascent existence, may you continue to bring so much joy, love, and laughter into our lives.

Semper ex animo,

Ninong Renzo