By Martin Genodepa

Early humans recorded significant aspects and events of their personal and communal lives through drawings, paintings, and engravings done mostly on rock or cave walls. As they were setting and solidifying their stories, ideas, and dreams in stone, they were also moving toward a uniquely human form of communication that flows through and connects time and space: writing.

The development of writing is correlated with the advancement of the human race in many fronts.

Various cultures developed their own writing systems—coded linear marks or strokes signifying sounds or utterances. Cuneiform, calligraphy, and scripts, including the local baybayin are a few examples of writing systems.

Before the invention of the printing press, the typewriter, and the computer, manuals on how manuscripts were to be made served as the bases for satisfactory print or cursive writing.

Like painting and drawing, writing by hand is an art form. Its many styles are visual abstractions of apprehended human perceptions and imaginations that have been turned into standard systems of codes and symbols. As visual representations, samples of handwritings may be read as signs that express meanings beyond what is conveyed by the thought of every single word that is spelled.

Writing has become an important part of modern basic education, so much so, that different educational institutions have developed iconic, if not idiosyncratic, styles of writing.

Writing is also a performing art. Handwriting primarily uses space and is dependent on movement, regardless of the writing surface or tool that is utilized. The act of handwriting is a performance that may be observed as a language of the body. It is personal and dramatic. Each stroke’s distinctive shape, form, or qualities betray the mind, the heart, the spirit to whom the hand that wields the brush or the pen yields.

Kinamot is Hiligaynon for making or doing something using the hands (kamot). Something skillfully done by hand is called handiwork; the term birthed the word handicraft — a

trade, work, or art done by hand, requiring much skill. Hence, anything made with or done using the hands – kinamot – is a display of skill and has, of late, become rare and rarefied.

It is a pity that writing with one’s hand, at once harnessing the mental and the physical faculties, and allowing coordination, control, and creativity to coalesce, is on the decline. Humans will be all the poorer for it!

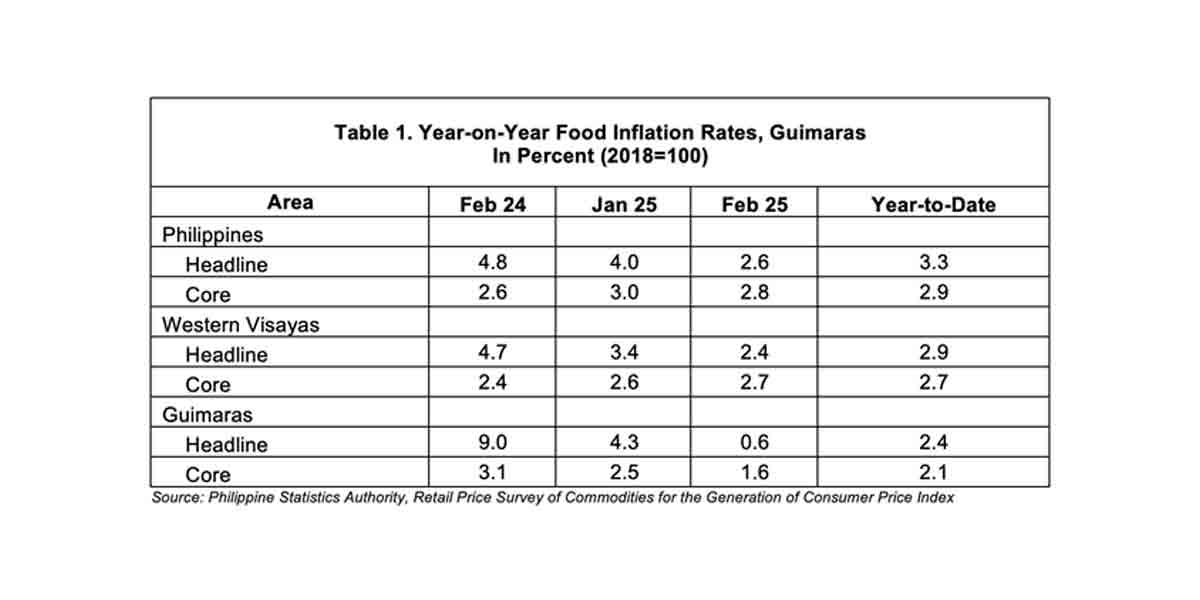

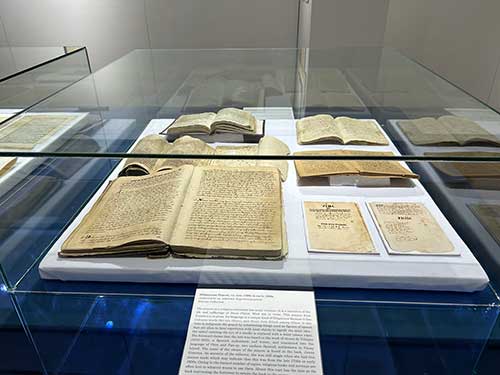

An exhibit of manuscripts and documents along with artworks that primarily employ penmanship is now on view at the UPV Museum of Art and Cultural Heritage (UPV MACH). It aims to give attention to the fast disappearing art of handwriting.

Kinamot – Writing Culture features among others Roman Catholic Hiligaynon novenas, Arabic calligraphy, Persian fatwa documents, Ethiopian religious scripts, Tibetan uchen, ventury-old postcards, greeting cards, lesson plans, school albums and zarzuela and comedya scripts.

The visual art made by some Ilonggo artists complete this show. Alex Española, in a fitting commentary on the disregard for its principles, handwrote the Bill of Rights on a black stained canvas Article III (2022). Melvin Guirhem intimated his anxiety as an artist in his extremely large acrylic and ink on canvas letter Liham ng Kahapon (2022). Nelfa Querubin literally professed her faith in her oil pastel painting Kaligtasan (2011), while Brenda Fajardo recreated the illuminated manuscript by taking on a social issues in Kalabaw Bibaw (1999) and Dao Indi Guid Catilao sang Calamay (1989).

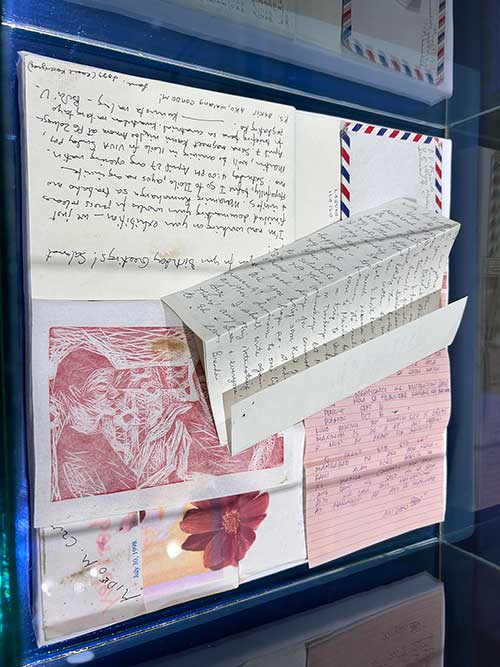

The autographs of two Filipino National Artists, Jose Joya and BenCab (Benedicto Cabrera) are among the highlights of the exhibit along with letters written by distinguished artists and cultural workers like Brenda Fajardo, Mideo Cruz, Iggy Rodriguez and Bobi Valenzuela.

Kinamot – Writing Culture is an exhibit that primarily reeks of nostalgia; but it also offers a veritable cache of learning objects on faith and life.