By Karol Ilagan, Andrew Lehren, Anna Schecter and Rich Schapiro

THIS STORY WAS PRODUCED BY THE PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE PULITZER CENTER’S RAINFOREST INVESTIGATIONS NETWORK AND NBC NEWS.

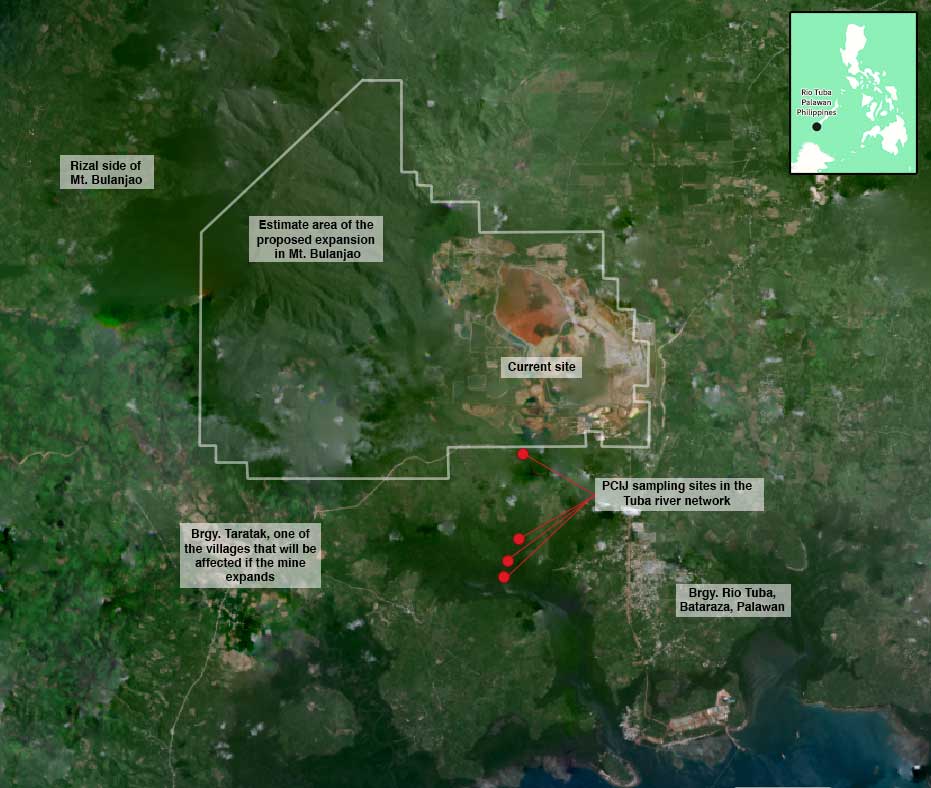

BATARAZA, Palawan – Narlito Silnay and Kennedy Corio share the same worry over the looming expansion of Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corp. in Mt. Bulanjao. Although they live in different towns and different sides of the mountain, the same forest ecosystem and river network link the two Pala’wans.

Among other things, Silnay and Corio fret about losing their source of water, the lifeline of indigenous and farming communities in the two towns. They both have a good reason to be concerned.

Three tests – conducted separately by Friends of the Earth Japan, Palawan authorities, and PCIJ – confirmed unsafe levels of hexavalent chromium in bodies of water where Rio Tuba’s wastewater is discharged.

Hexavalent chromium figured in the Julia Roberts film Erin Brockovich, in which an energy company was found polluting the water in Hinkley, California.

Hexavalent chromium is a form of the metallic element chromium. According to the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, chromium naturally occurs in rocks, animals, plants, soil, and volcanic dust and gases. When oxidized or exposed to elements, it comes in several different forms, including trivalent chromium or chromium (III) and hexavalent chromium or chromium (VI).

Trivalent chromium is supposed to be an essential nutrient for the body. In contrast, hexavalent chromium, which is generally produced by industrial processes, is toxic.

The Report on Carcinogens listed hexavalent chromium as a known human carcinogen, which means that it can cause cancer. According to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, repeated exposure to hexavalent chromium can cause a number of respiratory conditions, including asthma, bronchitis, itching, physical trauma to the respiratory tract, and lung cancer.

Japanese NGO finds unsafe levels of heavy metal

Friends of the Earth Japan (FoE Japan), a Tokyo-based international nongovernment organization, has been monitoring the waters surrounding the mine site for over a decade. The tests started because of reports of increased cough and other respiratory diseases, as well as skin lesions.

Hozue Hatae, a researcher at FoE Japan, said the results of a survey of 133 households prompted them to consult with experts, who recommended that FoE conduct water quality analysis.

Every year, from 2009 to 2019, Hatae and her team went to Bataraza to get samples from various locations during the dry season (March or April) and rainy season (August, September or October). The samples were taken to Japan for analysis.

Every year, FoE found that hexavalent chromium in the Togpon River, one of the sampling sites, exceeded safe levels or above 0.05 milligrams per liter (mg/L), the exposure limit followed in Japan as well as by the World Health Organization.

The unsafe levels were always detected during the rainy season, said Shigeru Tanaka, leading him to believe that the rainwater dissolves hexavalent chromium from the ore stockpile or from the ground and makes it flow down the river. Tanaka, director of the Tokyo-based Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC), also works with FoE Japan. He is engaged in field research to assess the human rights and environmental impacts of mining projects in the Philippines, Ecuador, Brazil, and Canada.

FoE Japan and PARC started looking into Rio Tuba in 2006 when Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd., along with its partner Nickel Asia Corp., set up Coral Bay Nickel Corp. (CBNC), the country’s first and one of only two nickel processing plants. Sumitomo is funded by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation, a government-owned bank that gives loans to companies investing abroad. Nickel Asia Corp. owns 60% of Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corp.

FoE Japan also found similar dangerous levels of hexavalent chromium in the waters of Taganito in Claver, Surigao del Norte, where Nickel Asia runs the Taganito Mining Corp. and Sumitomo operates Taganito HPAL Nickel Co., the only other nickel processing plant in the country.

The results of FoE Japan’s water analysis are portents of things to come if Rio Tuba expands operations. Mining a bigger area, said Hatae, could affect and extend the contamination into other watersheds.

According to Rio Tuba’s 2019 Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) obtained from the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), the expansion area lies within the catchments of five river systems: Canipan, Sumbiling, Tuba, Ocayan, and Iwahig.

The only affected watershed is Tuba, where the Togpon River is linked. Silnay’s tribe in Rizal relies on the Canipan River, while Corio’s tribe in Bataraza depends on the Sumbiling River.

Water samples also fail PCIJ and government tests

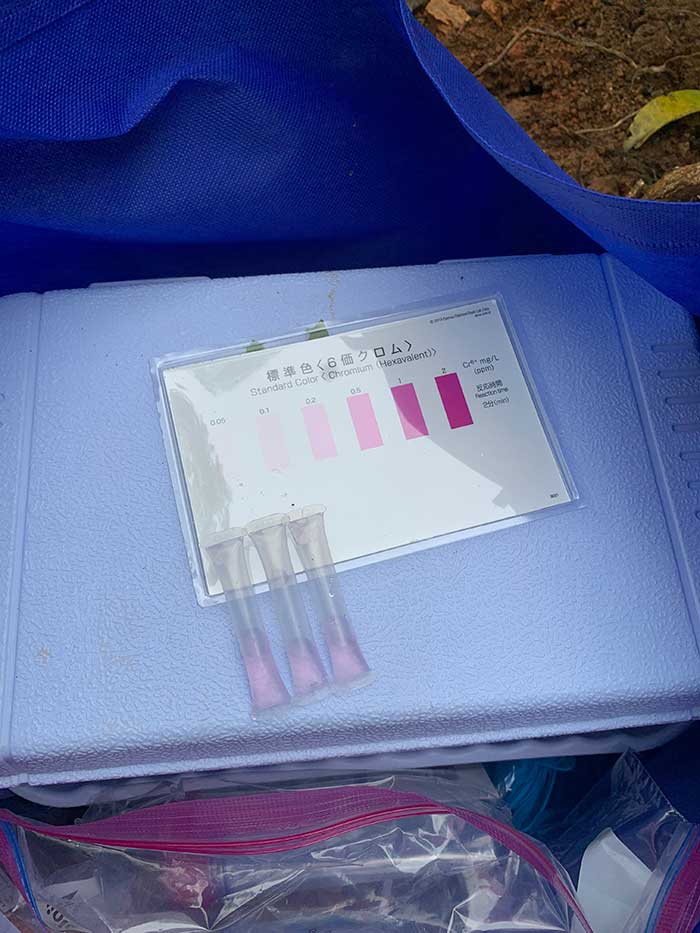

Hatae could not continue their annual testing in 2020 and 2021 because of travel restrictions brought by the Covid-19 pandemic. To check if the contamination persisted, PCIJ conducted its own sampling and testing in October 2021. PCIJ sought the guidance of FoE Japan, PARC, as well as Dr. Lynn Crisanta Panganiban, a toxicology professor at the University of the Philippines – Manila and Dr. Armando Guidote, a chemistry professor at the Ateneo de Manila University. For sampling parameters, PCIJ referred to EMB’s Water Quality Monitoring Manual.

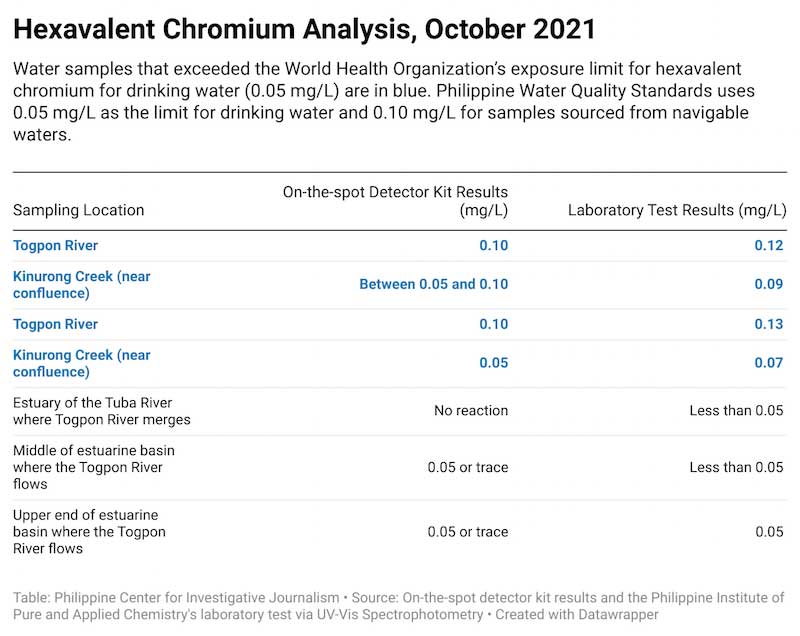

PCIJ’s testing, which used on-the-spot detector kits and laboratory analysis, confirmed FoE Japan’s findings. Four samples along the Togpon River and Kinurong Creek found hexavalent chromium levels higher than the WHO standard for drinking water.

In 2020, at least two quarterly tests conducted by the government’s Multipartite Monitoring Team (MMT) also found levels of hexavalent chromium exceeding Philippine water quality standards.

Samples in four of eight stations, which are also located along the Togpon and Kinurong waterways, had hexavalent chromium exceeding 0.05 mg/L.

These levels were above the standard for hexavalent chromium for Class SC water bodies or fishing waters under DENR Administrative Order No. 2016-08, which sets water quality guidelines and general effluent standards. In its report, the MMT however uses a lower standard, i.e., 0.10 mg/L.

MMT is the monitoring arm of the Mine Rehabilitation Fund Committee (MRFC). An independent body, the MMT is supposed to assist the Department of the Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) in monitoring the environmental impact of mining as well as miners’ compliance with environmental laws.

An excerpt of the MRFC’s meeting minutes discussing the 2020 sampling results stated that a resampling of the hexavalent chromium was conducted on Jan. 6, 2021 at five sampling stations. Unsafe levels of hexavalent chromium were still found in three sampling stations based on the results of three laboratories. One laboratory however found levels in all sampling stations within standards.

A Rio Tuba representative to the meeting said the company had been monitoring the hexavalent chromium levels since 2012 because of concerns in the community. But she noted that historically, the level of hexavalent chromium in the area was high. “There are still observed exceedances despite mitigating measures by the company,” the minutes read.

Hatae of FoE Japan said the issue was brought to the attention of Sumitomo, Rio Tuba, and Philippine authorities in 2012. Sumitomo told FoE Japan that Rio Tuba had started taking measures to reduce the hexavalent chromium flowing into the river. These measures included covering the nickel ore stockpile with canvas sheets, excavating the siltation pond, and putting activated charcoal around the exit of the siltation pond.

But the measures did not seem to work based on test results, Hatae said.

Experts assess risk

Nickel mines have been found to increase the release of soluble chromate into groundwater and surface water, according to experts. The risk grows when proper containment measures are not in place. But it’s difficult to establish a definitive link between a mine and high chromate levels without water test results prior to operations.

Two experts – Jennifer De France, team leader of drinking water quality at the WHO, and Murray McBride, a professor of soil science at Cornell University – said it was possible that the level of chromate in the water was a natural occurrence that resulted from high concentrations in underlying rocks.

Whatever the cause, it could be detrimental to the rice paddies in the area, McBride said.

“There is potential for crop damage from chromate accumulated in soil, as well as possible risk to human health if chromate levels in soils are too high,” McBride said.

Panganiban, a toxicology professor at the University of the Philippines – Manila, said it was difficult to assess how dangerous the levels were without information on how people used the water. The risk depended on the route of exposure – by mouth, through inhalation, or through the skin.

Panganiban, who made estimate computations using PCIJ’s laboratory results, said that at point of contact alone, the hazard value of the four sampling locations with levels above 0.05 mg/L would result in values between the range of 1.4 and 2.6. The safe level is below 1, she said. The hazard value or measure of risk is computed by dividing the results by the standard.

But the same levels yield a lower hazard value under a scenario evaluation. A scenario evaluation measures the exposure or intake rate of a person. Using WHO’s default factors, where an average person weighed 60 kilograms and drank 1.5 liters of water a day for 30 days, the hazard values are about 1.

Corio, a Pala’wan, said that before the mine was set up, tribe members slept by the river.

“In the summer, they built makeshift houses by the river. That’s where they slept. They fish there and together with their family and when the trees bear fruit like tabo, mararing, and mante,” he said.

But this is no longer the case now. Multiple people who live near the area said in interviews last month that locals stopped using the river for drinking water years ago after it developed a reddish hue.

“If the person doesn’t drink from there, he or she wouldn’t be exposed. If he or she has no exposure, then he or she would not get sick,” Panganiban said.

However, the toxicologist said other exposure routes needed to be considered because hexavalent chromium was more known to cause cancer when inhaled. In any case, if the water was found to have hexavalent chromium levels above standards, it should definitely not be used. Recent studies also showed that people might get sick if exposed to hexavalent chromium orally, she said.

Passive pollution?

Jose Bayani Baylon, spokesperson for Nickel Asia, questioned the standing of FoE Japan and the Environmental Legal Assistance Center (ELAC) that is helping members of the Pala’wan tribe, pointing out that they were not from Rio Tuba or Bataraza.

Baylon said Rio Tuba’s initial sampling in December 1996 already showed “escalated values of hexavalent chromium in nickel mining water before the peak of the mining operation.”

But he also said a 2018-2019 study by Rio Tuba and the National Institute of Geological Sciences at the University of the Philippines – Diliman showed that hexavalent chromium in surface waters exiting the mine were mostly below the limit of 0.1 mg/L while the metal in groundwater was generally undetected.

“The mine drainage system is designed to direct the mine surface run-off straight to the Rio Tuba River and not for drinking, irrigation, or agricultural purposes. Therefore, it is very unlikely that mine waters, or Cr6+ (hexavalent chromium) will enter the local water supplies,” Baylon said in a written response.

Tanaka of PARC acknowledged that pollution might be happening not necessarily because the company was bringing in toxic substances to the water. If the nickel ore is underground and does not touch oxygen or water, then it stays as a non-soluble state of nickel. Similar to chromium, once it is dug out and exposed to oxygen and water, it becomes a soluble, salient type of chromium like hexavalent chromium, which then goes into the rivers.

“From the mining companies’ side, they are digging what was already underground, in nature, and they are not touching the rest of it, but it is the not-touching part, leaving-it-there in an open pit is the part which is causing contamination,” Tanaka said. “It is not that they are actively creating this toxic substance. They are passive in their operations.”

In any case, Panganiban said government regulators needed to assess the risks, take the necessary action, and provide guidance to companies.

“They should be our watchdogs to really make sure that the industry is doing it well, so it’s going to be like a partnership…” she said. “Like, OK, you clean your backyard, but somebody has to make sure that cleaning is also correct.”

Regulators to look into issue

According to the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), mines undergo three levels of monitoring to assess whether measures work to prevent or mitigate the actual impact vis-a-vis the predicted impacts identified in the Environmental Impact Assessment. The company or project proponent, Multi-Partite Monitoring Team or the MMT, and the EMB office concerned conduct monitoring separately. The monitoring reports are then submitted to EMB and any violation is endorsed to the EMB Central Office. EMB checks for compliance with the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, Toxic Substances and Hazardous and Nuclear Waste Control Act and Solid Waste Management Act.

Mary Therese Gonzales of the EMB’s Environmental Impact Assessment and Management Division said the Mimaropa office was in-charge of monitoring Palawan mines. No violation has been endorsed to the EMB Central Office pertaining to hexavalent chromium exceeding standards in Rio Tuba, she said.

According to the Mimaropa office of the Mine and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), however, a notice of violation was issued to Rio Tuba in 2012 due to high levels of chromium concentration in the company’s effluent. This, Glenn Noble said, prompted the mining company to employ mitigating measures.

Noble, the newly appointed regional director of MGB Mimaropa, said the issue needed to be looked into. “This is one of the things that I’ll be discussing with them in the committee… so this could be addressed accordingly.”

PCIJ met with Bataraza Mayor Abraham Ibba in Rio Tuba in October. He initially agreed to be interviewed but later refused, saying he could not talk about the issue until after the elections. PCIJ also tried to reach him in November but he did not take the call.

Bataraza’s municipal health office could not also entertain PCIJ’s interview request because the officer in charge had contracted Covid-19.

Teodoro Jose Matta, executive director of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, said the council, although part of the MRFC, was not active in enforcement. But that will soon change.

“That’s part of our conditions that we will be monitoring strictly and that we have the authority to revoke the SEP (Strategic Environmental Plan) clearance if there are blatant violations,” he said.

Matta said the contamination was not taken into consideration before Rio Tuba’s 2014 clearance was issued.

“Nobody brought it up. But after that, someone did inform me that there were problems. And so right now I’m doing backdoor work,” he said.

The council is working to have its own laboratory by the end of 2022. –PCIJ, December 2021

Andrew W. Lehren is a senior editor with the NBC News Investigative Unit and a fellow with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

Anna Schecter is a senior producer with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Rich Schapiro is a reporter with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Rachel Ganancial of Palawan News and Elyssa Lopez, Martha Teodoro, Sofia Bernice Navarro, Ma. Cecilia Pagdanganan, and Kyla Ramos of PCIJ contributed research to this story.

Photographs: Kimberly dela Cruz

Infographic: Joseph Luigi Almuena