Economic difficulties arising from the pandemic have seen Grade 11 and 12 students from private schools flocking to public schools struggling to implement the K to 12 Basic Education Program. Over a hundred private schools offering senior high school education have closed because of low enrollment.

By Cristina Chi and Jan Cuyco

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

When Rizal High School in the country’s capital region opened the new term in October, the unprecedented increase in senior high school (SHS) enrollees –– Grades 11 and 12 –– made Assistant Principal Junie Serot worry.

The public high school in Pasig City is one of the country’s biggest. Because of the pandemic, the number of senior high enrollees exceeded the school’s holding capacity by more than a thousand students. At least 177 of them were transferees from private schools.

Even after classes began, Serot said Rizal High continued to receive a high volume of calls from parents begging the school to take their children in because they could no longer afford to pay private school tuition.

“‘Yung private [school students] ‘yung tinatanggap namin kasi wala na silang mapupuntahan kundi kami lang (We accepted private school students because they had nowhere else to go to but to our school),” Serot said.

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed a serious flaw in the Department of Education’s (DepEd) K to 12 Basic Education Program. When the government imposed two more years of high school to prepare students for work or college studies, it relied too much on private schools to offer Grades 11 and 12. There were not enough public senior high schools.

To help students who could not be accommodated in public schools pay for private education, DepEd handed out vouchers worth P8,750 to P22,500 a year. Parents absorbed the excess.

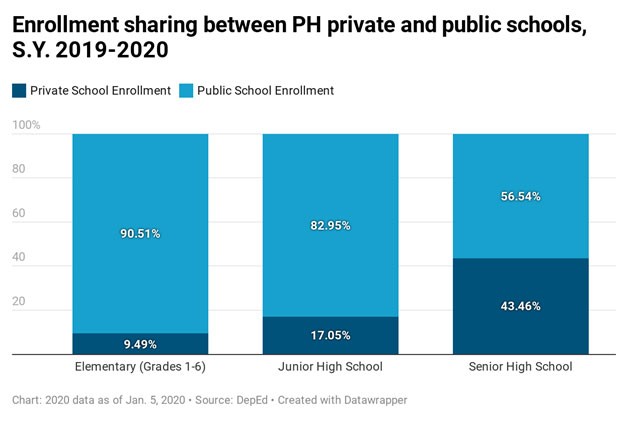

Many public school students availed themselves of the vouchers and transferred to private schools. As a result, in the first year of the K to 12 program in 2016, the proportion of senior high students in private schools nearly matched that of public schools –– 47% versus 53%. In elementary (Grades 1-6) and junior high school (Grades 7-10), private school enrollment accounted for merely a quarter.

Ninety percent of private school enrollees at that time were voucher recipients. Big business took advantage and put up chain schools. Examples are STI and APEC Schools, an Ayala Corp. subsidiary.

The subsidies fell short when the pandemic hit, however, forcing transferees from private schools to compete with public school students for limited slots.

Grade 11 student Melrick Celajes was one of the transferees to Rizal High School. He had attended private schools until this school year, when his father lost his job as a company driver earning minimum wage.

Celajes qualified for the senior high school voucher program (SHS VP), but the financial assistance was not enough.

“Parang hindi siya enough para mabawasan ‘yung burden … ng [private school tuition na] P100,000. Kung P20,000 lang ‘yung mababawas, medyo malaki pa rin ‘yung babayaran (I think this is not enough to lessen the burden… of private school tuition that can reach up to P100,000. If only P20,000 will be subsidized, the remaining cost will still be too high),” he said.

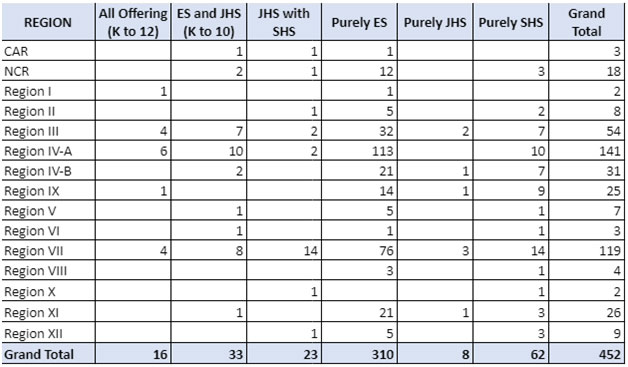

The pandemic hit many private schools hard. At least 452 private schools had to close amid low enrollment during the pandemic. Out of this number, 101 schools offered senior high school education.

Senior high school enrollment in private schools dropped to 800,000 this year, according to Rhodora Ferrer, executive director of the Private Education Assistance Committee (PEAC), a public-private body that administers state subsidies to private schools. The figure went down by about 200,000 from at least one million enrollees annually since 2017, she said.

The real extent of the problem remains to be completely understood as DepEd was still validating enrollment numbers when PCIJ requested the data.

Number of Private Schools that Closed in S.Y. 2020-2021, By Region

Relying on private schools to offer Grade 11 and 12

Former education secretary Armin Luistro, who rolled out the K to 12 program, said the subsidies were an “excellent form of arrangement” in which students chose where to pursue senior high. “If all of your programs are public schools, then parang wala ka nang choice (it’s like you no longer have any choice),” he said in a phone interview on Oct. 21.

The voucher program, under DepEd Order No. 66, has also “proven to be cheaper” for the government than if it were to run the program in overwhelmed public schools, he added.

Flora Arellano, president of E-Net Philippines, a network of civil society organizations for education rights, said these subsidies did not address issues on the quality of education in the country, and merely passed the burden to private schools.

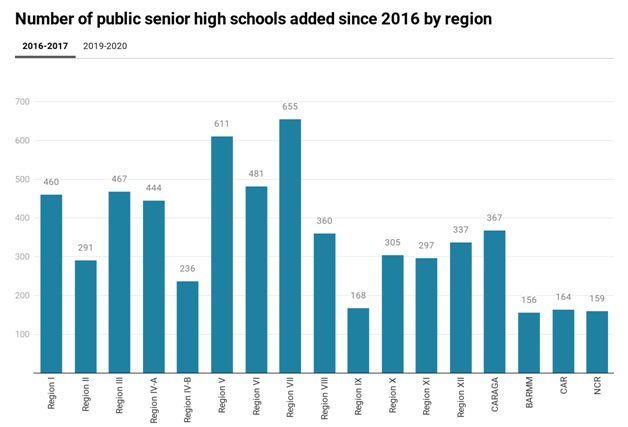

The number of private and public senior high schools climbed across all regions since 2016, reaching more students, according to a 2019 study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), the state-funded think tank.

But the same study showed that long-standing quality issues remained in the education sector even under the new senior high curriculum. Four years since implementation, the program continues to have unclear standards of assessment, a congested curriculum and inadequate resources, among other problems, it said.

Senior high teachers, who “made up for inadequacies in program inputs with their resourcefulness,” often lacked content mastery in highly specialized classes, the PIDS study found. Underscoring the problem was the general lack of teachers in bigger schools.

“There might not be enough qualified teachers especially for specialized subjects, and [this] shortage has led to mismatches between teachers’ specialization and subjects taught,” the report said.

A 2016 Commission on Audit (COA) report assessed the DepEd’s voucher program and concluded that the unreadiness of public schools to accommodate the country’s 1.4 million Grade 11 students in 2016 made the private sector a decisive player in the implementation of the K to 12 program.

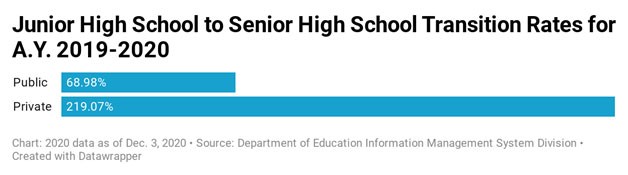

Last academic year, prior to the pandemic, 984,916 or 69% of 1.4 million public Grade 10 students moved up to a public senior high school, according to DepEd data on transition rates.

This was in stark contrast to private schools, which recorded a 219.07% transition rate.

Marieta Atienza, chief of the DepEd Education Management Information System Division, said this high transition rate meant that private school enrollees in Grade 11 increased significantly from Grade 10, possibly due to the number of public school students transferring to a private schools before Covid-19 struck.

COA recommendation: Build schools

COA told the government to address deficiencies in the public school system and not to rely on the resources of private schools. “Funds set aside to support these [private] institutions could be allocated to sustain and enhance the basic education services in public schools,” the report stated.

Arellano agreed. “Ang posisyon namin dyan, why not build more infrastructure that would be long-term? Hindi ‘yung napaka– temporary lang na ililipat mo sa private schools (Our position here is why not build more infrastructures that would be long-term? Instead of temporary solutions of allowing students to transfer to private schools),” she said.

She said schools should also rethink their educational content and pedagogy to address gaps in the K to 12 curriculum in the longer term. With or without the voucher program, private and public schools suffer from quality issues, Arellano said.

But all this is easier said than done.

In 2015, DepEd ordered every municipality to build a senior high school. Despite DepEd’s efforts, gaps remained especially in distant areas where low demand made it difficult to open public senior high schools.

“You don’t just give seats, but you have to give them access to quality education. The quality component is the one that is rather difficult,” PEAC’s Ferrer said.

Prior to the pandemic, public schools officials found out that their students preferred to transfer to private senior high schools, especially those opened by private universities, to get a foretaste of college life.

Victorino Mapa High School in Manila was unable to entice its own students to stay for senior high.

The school is close to Manila’s university belt, giving students the option to use DepEd vouchers to transfer to private schools and universities offering Grades 11 and 12.

School principal Butch Locara said it was hard to compete with neighboring private schools. Internal surveys from the previous school year revealed that not even 1% of the more than 3,000 junior high school students in V. Mapa High expressed interest to study senior high there.

“Madali lang naman kasi na magka-senior high kami. Pero paano ko iia-assure kung mismong mga estudyante ay hindi gusto mag-aral ng senior high dito? (It’s easy to set up a senior high school here. But how can I make sure that students will enroll if the students themselves say they do not want to study senior high in our school?),” Locara added.

When the pandemic hit and private school students knocked on their doors, the public schools were ill-prepared.

In Rizal High, the surge in enrollees this year has led to a teacher-student ratio of 1:40, beyond the recommended 1:35 ratio.

A shortage of teachers ensued during the third year of SHS implementation, Serot said. But the school felt the problem more acutely this year as its 101 teachers struggled to handle a population of 4,094 students.

Aside from a lack of guidelines for promotion, the number of teacher positions in the school has remained unchanged since 2016. Some faculty members have been in the same teaching position with the same salary grade as when they were hired.

“We have one teacher who has been a Teacher 1 (entry-level teaching position with lowest pay) for five years already despite having a master’s degree,” Locara said, adding that the school was working on the promotion of teachers who have been long qualified for it.

Teacher groups in 2015 feared that the voucher scheme would allow the government to evade the responsibility of hiring more teachers and building more classrooms in public schools, according to a joint study by the Asia South Pacific Association For Basic And Education (ASPBAE) and E-Net Philippines.

Urgent review

There have been calls for an urgent review of the K to 12 program over issues that hounded it even before the pandemic.

K to 12’s goal was to make students employable without going to college. But the voucher program did not benefit the marginalized students who needed it the most.

Since the voucher cannot cover all school fees, beneficiaries usually came from socioeconomic classes C and above, or those who earn an average monthly income of P15,000 to P100,000 and above, Ferrer said.

“If you are a [class] D and E, it’s a little difficult to be in a private school. What is given is not a full scholarship,” she said.

With the government leveraging on private investment, Arellano said this might come at the risk of “deepening the gap between the marginalized and affluent sectors of students.”

E-Net Philippines’s Arellano said only financially capable students who could pay top-up fees were able to transfer to private schools.

For less affluent families, the choices were slimmer. A 2015 ASPBAE and E-Net study showed that the poorer 30% of Filipino families spent an average of P7,400 per month and only P148 went to education.

“This certainly is too small to send and keep children in secondary school,” the study added.

The subsidies have been going to “students enrolled in high-paying private schools” who can afford education even without government subsidies, and yet became voucher beneficiaries, according to a 2016 COA report.

This was because the students’ financial capacity was not considered in qualifying for the SHS VP or for scholarship grants or programs, to conform with the provision of Section 22 of Republic Act 10533 or the law that mandated the K to 12 reform.

“The voucher program does not consider how students from far-flung areas will be able to go to urban centers where most private schools are located,” Arellano said.

Ferrer said it was clear the senior high program was “destined to fail” without the voucher program.

“If these students cannot be supported, and they cannot stay in the private schools without support, they cannot be absorbed by the public schools. Because they don’t have enough seats for them,” Ferrer said.

The situation could get worse. The pandemic sank the country’s economy in 2020, with gross domestic product (GDP) falling by 9.5% in 2020, the worst contraction since World War II.

The Grade 11 student Melrick Celajes, who earlier had doubts about transferring to Rizal High in Pasig City, said his new school had so far exceeded his expectations.

“It’s a very stereotypical idea that private schools offer better education than public schools. Most people think [that if it’s] private, education [is better], when it’s not really the case. [There are lesser known schools that give decent education,” he said.

Cristina Chi and Jan Cuyco are journalism students from the University of the Philippines – Diliman.