By Ricardo E. Escanlar III

(Atty. Ricardo Escanlar III is a faculty member of the College of Law of the University of San Agustin and a geologist who has extensive industry experience)

I just finished my first year of teaching law. The current pandemic has made the start of my career as a law school professor rather interesting, to put it kindly.

COVID-19 and its effects on people’s earning capacities, travel rights and mental health have imposed a barrier to those who would have wanted to study law, but cannot, because of a lack of finances, poor internet, no viable place to study, stress, depression, or many other reasons.

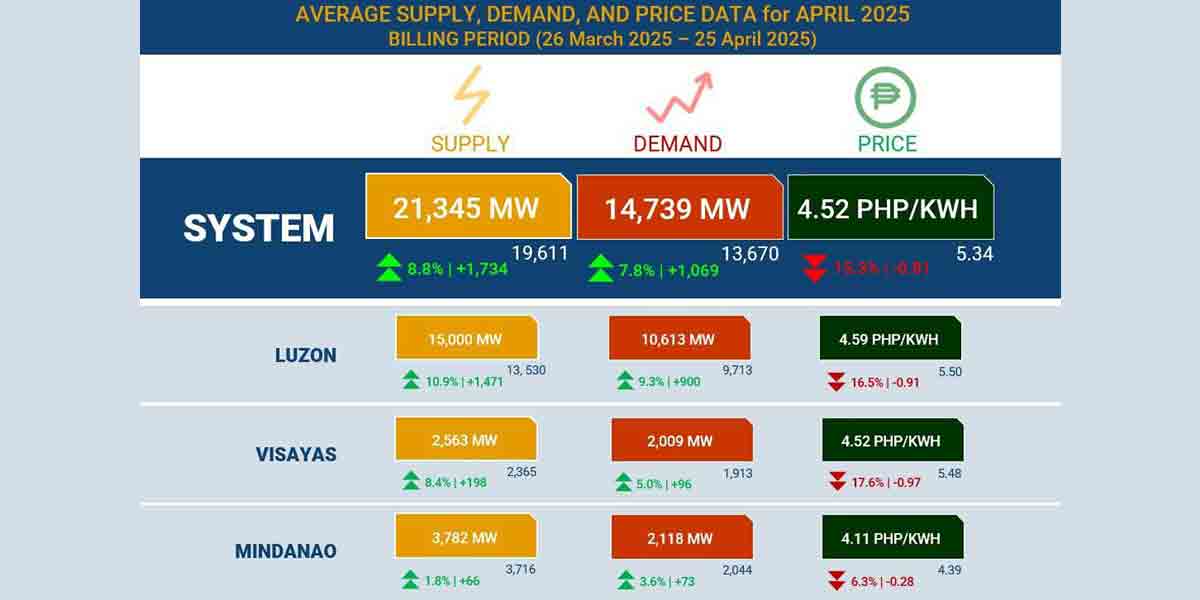

Those who are fortunate to have been able to enroll haven’t been spared from difficulties either. There are moments where I can feel my students’ ability to learn being limited by the lack of sufficient infrastructure in this country. There have been instances where students haven’t been able to attend classes because of power interruptions, numerous times where they got disconnected from the lecture because of poor internet, and also occasions where they weren’t able to submit their assignments within the deadline because their data connection failed them all of a sudden.

And it’s not only my students who are having problems. Even I had to cancel class because of power interruptions and internet disconnections. I spent ten minutes discussing a landmark case such as Oposa vs. Factoran, or the Rules of Procedure for Environmental Cases (RPEC), and as it turned out, I was only talking to myself because I lost my signal.

These are not ideal circumstances for teaching, and definitely not ideal circumstances for learning. It made me feel guilty for the times I took going to school for granted.

However, as much as we would want to rush the process of returning things to how they once were, we cannot. Scientifically, it has been shown that we are facing a serious enemy, one that can claim the lives of millions if left unchecked− and has already claimed the lives of millions worldwide as it had gone unchecked. And legally, jurisprudence has held that the right to life has primacy over the mere privileges to study, and eventually, practice law.

What, then, would be the fairest and most equitable thing to do? Certain voices have proposed for a suspension of classes, given that the pandemic has imposed an unfortunate selection process wherein the opportunity to study is not available to all, but only to those with the means to. Another proposal is to implement a “no-fail” policy, given that students cannot be expected to perform as well in an online setting as compared to regular face-to-face classes, and also taking into consideration the hardships they are facing during the pandemic. The rationales for these proposals are sensible.

But then again, while education is a right, legal education is a privilege. Furthermore, while COVID-19 will inevitably cause an impact on how the study of law is to be done in this country, legal education must still go on. And part of providing quality legal education is establishing academic standards− standards which, while made malleable in light of the current predicament, remain present.

It must be said that the more dangerous possible alternative outcomes are, if we implement the first proposal, to not have any future lawyers, and if we implement the second proposal, to allow students without the requisite aptitude and attitude to become lawyers. These would appear to be the best-case scenarios for those who want to sabotage and topple whatever is left of our constitutional democracy.

That is something we cannot allow to happen, and as such, we continue to try to provide law students the quality legal education they deserve in these times. And we continue to try to produce quality future lawyers that this country deserves in these times.