A new study published in the Journal of Mammalogy on April 23, 2021 confirmed the recent extinction of three previously unknown species of giant rodents that live only in the Philippines.

Locally known as buot or bugkon, the giant cloud rats live in trees and eat leaves, buds, and seeds. They have furry or fluffy tails and striking fur color. These giant rats and their relatives are members of an ancient branch on the tree of life that arrived from the Asian mainland about 14 million years ago. All three of these newly discovered species are thought by the authors to be extinct.

The largest of the fossil clout rat is the Carpomys dakal, named so because it is much larger compared to the known living species in the same genus, Carpomys melanurus and Carpomys phaeurus. Dakal means big or large in several languages in northern Luzon, including in the Itawes, Ibanag and Agta languages. The second fossil species, Crateromys ballik, is slightly smaller than the living Crateromys species on Luzon, Crateromys schadenbergi. Ballik means small in the Dupaningan Agta language. The third species, Batomys cagayanensis, is named after the place where the archaeological sites are located, the Cagayan region of northeastern Luzon. The scientific names of the three new species of fossil cloud rats were chosen using vernacular terms from Philippine languages.

Dr. Janine Ochoa, lead author and an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of the Philippines – Diliman, said the smaller-sized mammals were understudied probably because researches were focused on open-air sites where the large fossil mammal faunas were known to have been preserved, rather than the careful sieving of cave deposits that preserve a broader size-range of vertebrates including the teeth and bones of rodents.

“We have had evidence of extinct large mammals on Luzon for a long time, but there has been virtually no information about fossil of smaller-sized mammals,” said Dr. Ochoa.

The extinct mammals previously known from Luzon include two types of elephants, a species of rhinoceros, a giant hog, and relatives of the living dwarf water buffalo called the tamaraw.

Marian Reyes, a zooarcheologist at the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) and one of the authors, said that some of the fossils that were excavated in the 1970s and 1980s were in the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) awaiting detailed studies.

“When we began to analyze the fossil material, we were expecting fossil records for known living species. To our surprise, we found that we were dealing with not just one but three buot or giant cloud rat species that were previously unknown,” said Reyes.

NMP Director-General Jeremy Barns welcomes the publication of the study and reiterated the NMP’s commitment to contribute to the world’s body of knowledge through scientific researches and fieldworks.

“Our thrust is three-fold: educational, scientific and cultural. We have experts and scientists working in the museum, and we make sure that they are fully supported. All these are part of our quest to document and preserve everything that is part of our Filipino heritage,” said Barns.

Meanwhile, Dr. Lawrence Heaney, Negaunee Curator of Mammals at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, welcomes the new discovery as an affirmation of faunal diversity in the Philippines.

“Our previous studies have demonstrated that the Philippines has the greatest concentration of unique species of mammals of any country, most of which are small animals, less than 200 grams, that live in the tropical forest. These recently extinct fossil species not only show that biodiversity was even greater in the very recent past, but that the two that became extinct just a few thousand years ago were giants among rodents, both weighing about a kilogram. They were big enough that it might have been worthwhile to hunt and eat them.”

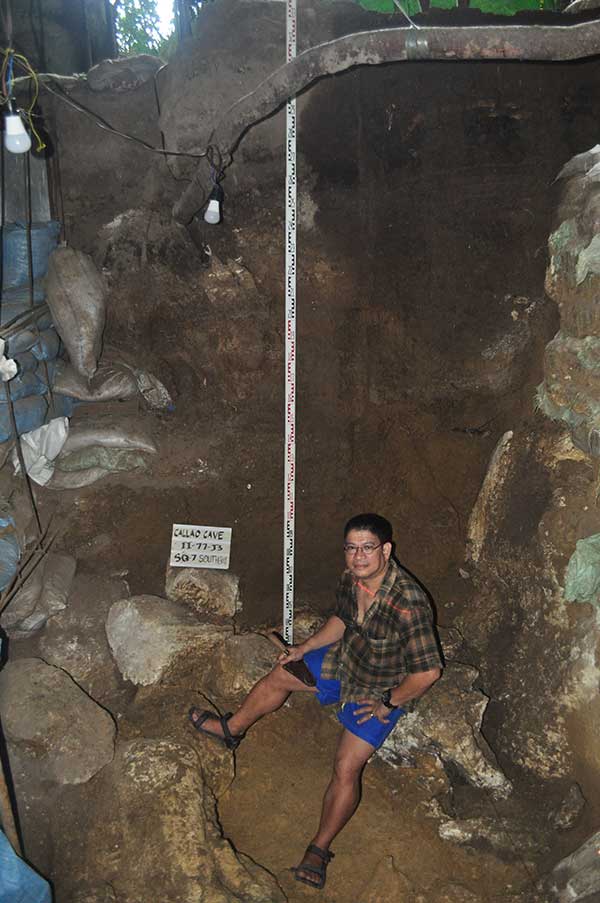

The newly recorded fossil species came from Callao Cave, where a previously unknown species of human, Homo luzonensis was discovered in 2019, and several adjacent smaller caves in Peñablanca, Cagayan Province. Some specimens of all three of the new fossil rodents occurred in the same deep layer in the cave where Homo luzonensis was found, which has been dated at about 67,000 years ago.

One of the new fossil rodents is known from only two specimens from that ancient layer, but the other two are represented by specimens from that early date all the way up to about 2000 years ago or later, which means that they were resilient and persistent for tens of thousands of years. “Our records demonstrate that these giant rodents were able to survive the profound climatic changes from the Ice Age to current humid tropics that have impacted the earth over tens of millennia. The question is what might have caused their final extinction?” adds Prof. Philip Piper, a coauthor based at the Australian National University.

A clue might be in that the last recorded occurrence of two of the species is around 2,000 years ago or shortly after. This is after the first arrival of agricultural societies and the introduction of animals like domestic dogs, pigs and macaque monkeys to the Philippines. “While we can’t say for certain, but this implies that humans likely played some role in their extinction,” said Professor Armand Mijares from the University of Philippines, who led the excavations of Callao Cave.

“Our discoveries suggest that future studies that look specifically for fossils of small mammals may be very productive, and may tell us a great deal about how environmental changes and human activities have impacted the really exceptionally distinctive biodiversity of the Philippines,” said Dr. Ochoa.

And such studies may also tell us a lot specifically about the impact of over-hunting on biodiversity, notes Heaney. “This is something we need to understand if we are going to be effective in preventing extinction in the future.”