A nickel mine is on the brink of a major expansion in Mt. Bulanjao, a rainforest system considered by indigenous peoples as their ancestral home and protected by a Palawan conservation law.

By Karol Ilagan, Andrew Lehren, Anna Schecter and Rich Schapiro

THIS STORY WAS PRODUCED BY THE PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE PULITZER CENTER’S RAINFOREST INVESTIGATIONS NETWORK AND NBC NEWS.

BATARAZA, Palawan — Jeminda Bartolome, a farmer, points to the rice paddies surrounding the foot of a mountain. “That,” she says, “is our source of livelihood.”

Bartolome scans the sprawling landscape that has a lush green mound for a backdrop. At least six rivers flow downhill to irrigate their farmlands. “Kaya kapag nasira iyan, sira na na rin ang aming sakahan (Once the mountain is destroyed… our farmlands will also be destroyed),” she says.

Palaweños call the mountain Bulanjao. It’s the last of the rainforest system that straddles one of the world’s most biodiverse places. Pangolins and horned frogs make their home here, as do other endangered and endemic plants and animals. But for nearly two decades Mt. Bulanjao has been at the center of a tug-of-war between those who live and depend on the land and those who want to profit off it.

The Pala’wan tribe and farmers in this southernmost tip of Palawan island have relied on the mountain for generations. It is also here, in the 1970s, when miners came and dug up the earth to help sustain the nickel needs of the world.

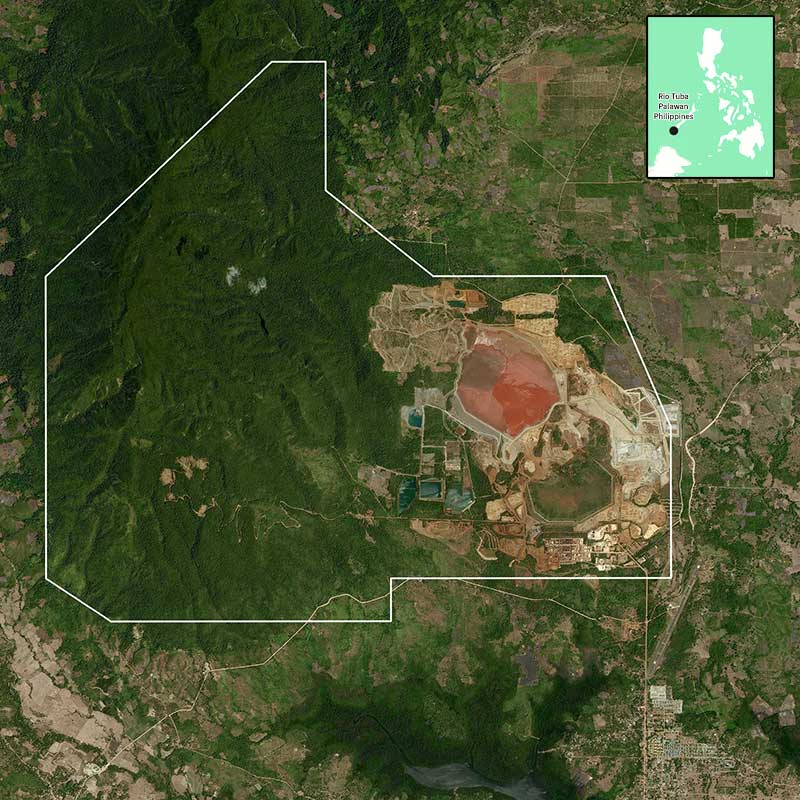

Now ore reserves in Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corp.’s 990-hectare site will soon be depleted. For 18 years, the company went through bureaucratic hoops to annex its 3,548-hectare claim on the mountain. Scientists argue that mining Mt. Bulanjao will mean a significant loss especially since saving forests is critical to addressing the impacts of climate change. Palawan is among the top provinces that lost a lot of forest cover — nearly 30,000 hectares — from 2003 to 2015. Meanwhile, the government has turned to the mining industry to boost revenue and create jobs.

Through the years and as nickel became an important metal for renewable energy technology, the layers of legal protection over the mountain were stripped through changes in land use and environment zoning maps, which accommodate mining. Today the miner is on the brink of a major expansion.

In October 2019, the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) gave conditional approval to Rio Tuba’s application to renew and amend its Mineral Processing Sharing Agreement (MPSA). With two of four requirements accepted as of writing, the mining firm is almost ready to operate at Mt. Bulanjao, most of which had originally been designated as “core zones” or areas of maximum protection by Palawan law.

The area that will be mined, officials said, covered 2,500 hectares or roughly the size of 57,524 basketball courts.

It is a familiar narrative, one that has happened in many parts of Palawan and across the country. Rio Tuba is the latest flash point of indigenous and local communities’ fight for their stake on land against the promise of “sustainable development” that the government claims mining would bring.

The irony is: Rio Tuba is prompted to dig more nickel to power electric vehicles being sold by Tesla, Toyota and other automakers. The transition to clean energy is coming at a high cost to forests, rivers, and people in the Philippines’s last ecological frontier.

RAINFOREST REZONED

Rio Tuba, like all mines in the Philippines, is operating on borrowed time. Mines are not supposed to operate indefinitely because mineral resources are finite. In fact, Rio Tuba’s contract was supposed to expire on Oct. 8, 2021. At its production rate, Rio Tuba’s ore reserves will be depleted by 2023, according to the MGB.

But Rio Tuba’s mine life was given a new lease when local authorities reclassified land use designations and issued permits. This facilitated the miner’s application to renew its MPSA and cover parts of Mt. Bulanjao.

Under Republic Act 7611 or the 1992 Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan (SEP) Act, natural forests, including first-growth forests, residual forests and edges of intact forests; areas above 1,000 meters, mountain peaks or other areas with very steep gradients; and endangered habitats and habitats of endangered and rare species were designated as “areas of maximum protection” or “core zones.” In core zones, human disruption is banned and only traditional tribal activities are allowed.

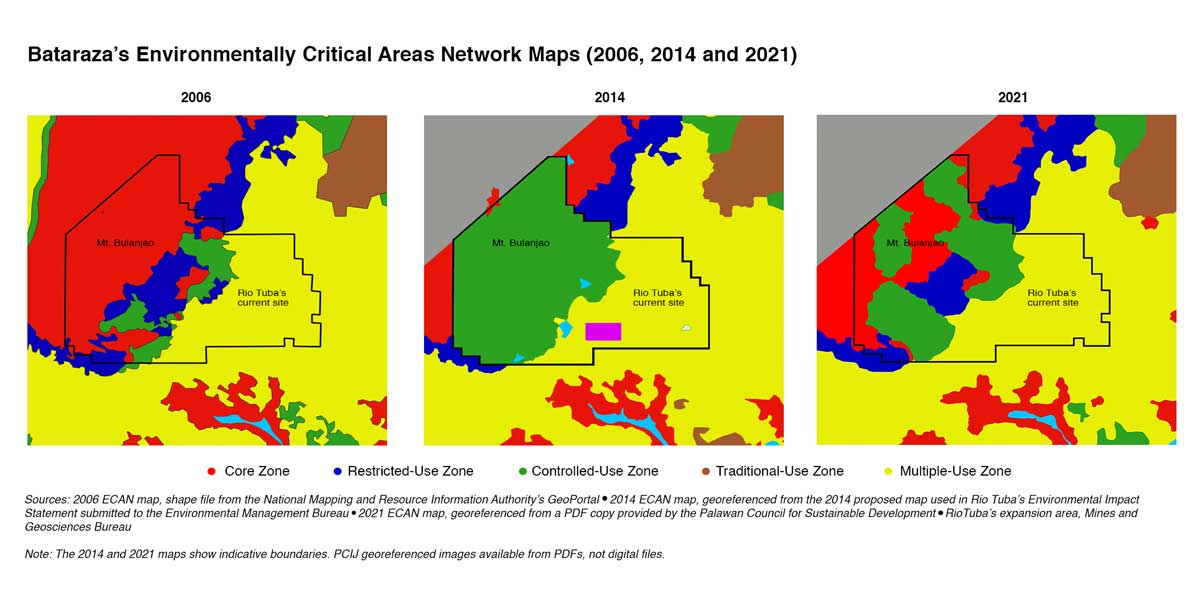

The concept of core zones is part of the Environmentally Critical Areas Network (ECAN) map, which was conceived to protect Palawan’s forests and biodiversity vis-a-vis development plans. Next to core zones are four buffer zones, which allow regulated use.

Before any type of development is done in Palawan, entities must secure a Strategic Environmental Plan (SEP) clearance from the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), a multisectoral body tasked to implement the 1992 law, to ensure that the plan is not in conflict with the ECAN zoning.

When Rio Tuba applied for contract renewal and amendment, more than half of the MPSA area encroached on core and restricted-use zones of the approved 2006 ECAN map. According to Rio Tuba’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) obtained from the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB), 39.64% of the area was within the core zone and 13.06% was within the restricted-use zone. Also, 10.83% was within the controlled use zone and 36.47% was within the multiple-use zone. The SEP clearance could not be issued at the time.

Between 2008 to 2010, the local government of Bataraza and PCSD issued resolutions and ordinances that led to the revision of the Municipal Comprehensive Land Use Plan (MCLUP) and the ECAN zone map. Officials designated as an “Established Mineral Development Zone” areas up to 1,000 meters above sea level at Mt. Bulanjao.

On May 30, 2008, the PCSD issued a resolution saying it had no objections to the revised ECAN map that, among others, sought to reclassify the core zone within the expansion into a mineral development area. Bataraza’s Municipal Development Council approved this in November 2009. The Palawan Provincial Board followed suit in January 2010.

Because of the revision, the coverage of the core zone decreased while the coverage of the controlled-use zone increased. According to Rio Tuba’s EIS, the PCSD Executive Committee approved the revised map in September 2014 and presented it to the PCSD in October 2014.

The Palawan sustainable development council granted the SEP clearance for the proposed expansion in December 2014, which was amended in September 2015 to include the PCSD chairman’s signature. The council’s only condition was that Rio Tuba should not mine in elevations of 1,000 meters above sea level in the revised ECAN map. This area was 4.1 hectares, according to Rio Tuba’s EIS and Environmental Compliance Certificate.

Rio Tuba finally got a break in October 2019, more than 16 years since it filed an application in July 2003, when the MGB renewed and expanded its MPSA, subject to regular conditions required of mines. The issuance of the SEP clearance in 2014 was pivotal to the MGB approval.

Jose Bayani Baylon, Nickel Asia’s spokesperson, contended that every law was subject to amendment and revision. The PCSD, he said, believed that the word “sustainable” in its mandate called for sustainable development in whatever form it came. “And so they, together with the Municipality of Bataraza in which we operate, have decided to come up with a new land use plan, allowing mining in a certain area, but not above a certain altitude,” he added.

PCIJ met with Bataraza Mayor Abraham Ibba in his office the day after he filed his intent to run for mayor again in 2022. He initially agreed to be interviewed but later said he could not talk about the issue until after elections. PCIJ also tried to reach him in November but he did not take the call.

PCIJ also sought an interview with Palawan Gov. Jose Alvarez who chairs the PCSD. Alvarez forwarded the request to the council staff.

LOCAL OFFICIALS REVISE ECAN MAP ANEW

Teodoro Jose Matta, PCSD executive director, said the ECAN map was revised again in June 2021, which led to the issuance of a new SEP clearance to Rio Tuba this year. The lawyer and his staff also said the area Rio Tuba would mine was reduced to about 2,500 hectares. Similar to the old condition, no core zone would be touched, he said.

PCSD staff provided PCIJ a scanned copy of the 2021 ECAN map. This time, the revision was partly based on a biodiversity assessment of Mt. Bulanjao, considering “newly available scientific data, existing development and current circumstances.”

Without access to a digital file, it was difficult to measure how much had changed from the 2006 and 2014 ECAN maps. A scan of the map however showed that what used to be core zones were still converted to controlled-use zones. (See infographic.)

PCIJ also requested a copy of the SEP clearance supposedly issued this year by PCSD. What PCIJ received from the council staff however was a copy of the previous SEP clearance that was the basis forthe 2019 MGB approval.

The MGB as well as the Environmental Legal Assistance Center (ELAC), the nongovernment organization that has a representative in the PCSD, were not aware of the supposedly new SEP clearance.

According to MGB’s Mimaropa office, Rio Tuba still followed the 2019 MPSA based on the 2014 SEP clearance. In fact, PCSD and ELAC remained locked in a legal dispute over the latter’s bid to recall this clearance.

Baylon said there was still no official revision of the ECAN map. But the mining company estimated that within the amended MPSA, some 1,000 hectares would be retained as core zone and another 340 hectares as restricted-use zone.

“Most of these areas fall to the other terrestrial criteria of core/restricted-use zones (steep slopes, critical local watershed, or retained criteria from the first edition of the ECAN map),” he said in a written response.

TRIBE MEMBERS, ELAC CHALLENGE RIO TUBA CLEARANCE

To Kennedy Corio and other members of the Pala’wan tribe, who asked not to be named, the issue was their survival.

“Ang aming kabuhayan kasi, hindi kami mabuhay sa bayan. Hindi kami mabuhay kung saan lang. ‘Di bale sana ‘yung may pinag-aralan, pwede. Pero ‘yung sa amin hindi kami mabuhay kung saan (It’s because our livelihood, we can’t live in the town center. We can’t just live anywhere. It’s possible for those who are educated. But for us, we can’t just live anywhere),” Corio said.

The Pala’wan who live in the sitios on the foothills of Mt. Bulanjao rely on its natural resources for food, potable water, building material for their homes, medicine and livelihood. Beyond their basic needs, the father of seven was worried about how they would be able to pass their culture to their children and their children’s children.

“Mawawalang lahat. Mawawala lahat ng hayop na hindi nakikita [sa labas ng bundok]. [Mawawala] ang aming kabuhayan, (Everything will be gone. The animals that you don’t see beyond the mountain will be gone. Our livelihood will be gone),” he said.

Corio is among the respondents who filed an administrative petition to recall the SEP clearance issued to Rio Tuba in 2014. Represented by Grizelda Mayo-Anda of ELAC, the petitioners alleged that Rio Tuba’s project would damage the environment in Mt. Bulanjao. It also violated the SEP law and Executive Order 23, the log ban in natural and residual forests issued by President Benigno Aquino III in 2011, they argued. They claimed that the completion of an environmental impact study and remedial measures to mitigate the impact of mining were immaterial.

For Baylon, the case against the mining company should be dismissed because PCSD issued the SEP clearance in accordance with the law.

PCSD’s Matta claimed the issuance of the 2014 SEP clearance might not have reflected the true intention of the council. “The council was torn … It was divided… So there was, there was no intention to give a green light at all — to mining in core zones. Definitely not core zones,” he says.

Asked why the SEP clearance was still released, Matta, who joined the council in 2020, could not give a firm answer. “Well, maybe that was the policy at the time. Perhaps, that was the policy at the time … I can only [guess] what their wisdom was at that time, because I’m only one member.”

In his opinion, however, the old SEP clearance was superseded by a new clearance that PCSD supposedly issued based on the 2021 revised ECAN map.

Mayo-Anda, who was not aware of the new SEP clearance, said the ELAC filed the case after learning from their NGO representative that there was no consensus among the council members on the SEP clearance issued to Rio Tuba in 2014. This, she said, means the validity of the SEP clearance was seriously in doubt, making the 2019 MPSA approval tenuous.

For his part, MGB Mimaropa Director Glenn Noble said the bureau was in no position to question the PCSD over the SEP clearance. “We always look at the document with the presumption of good faith, presumption of regularity. The only question that we’d like to (ask) is whether there really was an SEP clearance issued by PCSD. Is it valid? Rather than, is it a legitimate document?” he said.

Rio Tuba’s zoning issue is not isolated. Since PCSD was established in 1992, zones have been revised multiple times in various Palawan towns. In fact, Rio Tuba’s original expansion plan included ancestral domains on both sides of Bataraza and the neighboring town of Rizal. But the company decided to defer the application for the 667-hectare claim in Rizal because it is a restricted area. (See related story: A TRIBE DIVIDED)

Baylon said Rio Tuba needed to secure an environmental compliance certificate first for the Rizal claim. Before that, an endorsement and a clearance from the PCSD must be obtained.

“As most of the mineralized area is in a restricted classification under SEP (Strategic Environmental Plan) law, where mining is not allowed, the LGUs concerned [have] to first lobby for the conversion of its land use/ECAN map and convert these mineralized areas into development or other industrial-use zones,” Baylon said.

For this to happen, PCSD has to deliberate and sign off on the conversions on the ECAN zone map.

“Without such modification, a SEP clearance will be rendered useless as mining or other environmentally critical activities/projects will still not be allowed in the restricted areas,” Baylon said.

Mayo-Anda was alarmed that zones were being changed without solid science to back it up and without consultations with the community. “It’s just the LGU saying, ‘Okay, the local officials want it because they want to earn from the mine,’” she said. “But is that fair? Is that fair for the future? There should be a sustainable development goals framework there.”

Mayo-Anda also pointed out that under Section 9 of the SEP law, all natural forests, including Mt. Bulanjao, are areas of maximum protection.

STUDIES: SOCIETAL LOSS FROM MINING

ELAC’s arguments in its petition included results from two scientific studies, which concluded that mining should not be allowed in Mt. Bulanjao. The two studies were both conducted or led by PCSD with other organizations. Despite these findings, the SEP clearance was issued in 2014.

In 2011, the PCSD staff conducted a study to help decide whether mining could be a desirable means of economic development in Palawan. The question was: Should an identified mineralized area be mined out or better left alone?

PCSD worked with Palawan State University to conduct a total economic valuation of the Mt. Bulanjao forest ecosystem preservation as well as a cost-benefit analysis of the proposed mining project. The study looked at two sets of mining areas in Mt. Bulanjao: three parcels covering 676 hectares and core zones covering 529 areas.

Total economic value is derived from computing for both the “use values” (timber, non-timber forest products, recreation, research, soil conservation, carbon sequestration and the like) as well as the “non-use values,” the bequest value or its value of the area in the future.

A cost-benefit analysis was also done to determine the net social benefits with and without the mining operation in the area.

The research team found that mining in the two sample areas in Mt. Bulanjao would result in losses to society of at most P203.4 billion and P129.13 billion, respectively. In short, it did not make sense to mine the areas given their ecological value.

For Patrick Regoniel, an environmental science professor at Palawan State University who helped conduct the 2011 study with PCSD, the big loser may be the environment, which will be destroyed if a decision isn’t made to take care of it now.

“You will notice that the net present values that they placed here (cost-benefit analysis) are all given negative values, [which] means that there is loss,” he said.

To be fair, the study does not include the efforts of the mining company to reforest and to mitigate any negative effects on the environment, which may change the numbers, he said. This needs to be considered given that resource management or the use of mineral resources requires strict environmental protection, he added.

Reforestation may also contribute to the social benefits gained through mining operations, because restoration or reforestation may improve or enhance the area after the mine is exhausted. However, nickel mining requires stripping the land of soil, he pointed out. “So you are removing the forests, removing everything there. So, all the fertile areas are removed. And of course, you expect that there will be environmental costs. And that is through erosion, among others,” he said.

The other study, conducted by the Center for Conservation Innovations PH in partnership with PCSD and Conservation International Philippines Foundation in 2017, attested to the high conservation value of the mountain, making it incompatible with mining.

High Conservation Value Areas (HCVAs) are natural habitats that possess inherent conservation values, including the presence of rare or endemic species, provisioning of ecosystem services, sacred sites, and resources harvested by residents.

The study found that all HCVAs in the western part of Mt. Bulanjao were in “clear present danger and warrants immediate measures to ensure its security.” These are under rapid degradation due to land use change. An imminent threat of massive conversion is also found in all of the HCVAs in west Mt. Bulanjao because of the planned mining activity.

Although the study was confined to the west side of the mountain in Rizal, where Rio Tuba’s application was postponed, ecologist Neil Aldrin Mallari said the same findings also applied to other parts of Mt. Bulanjao given that the mining expansion plan overlapped with biodiversity and forest areas.

Mallari, who has a doctorate in ecology, conservation and management, is the executive director of the Center for Conservations Innovation PH. He is among the expert witnesses who will be cross-examined in the administrative case filed by ELAC to recall Rio Tuba’s SEP clearance. If anything, the scientist sees a window of opportunity for PCSD to revise the ECAN zoning to match conservation requirements.

The 2017 study likewise found a clear mismatch between the conservation requirements of the HCVAs in the western part of Mt. Bulanjao and the conservation prescriptions offered by the ECAN. Some HCVAs are outside core zones as there are areas designated as core zones but do not overlap with HCVAs.

The scientist also said mining companies, while may be inclined to cut corners to attain business objectives, would eventually comply with government regulations. “It’s just a sad fact that the government regulation is so weak on the science part. And you know, we have to pay for that weakness,” he said.

“Buying off communities… building schools… giving motorbikes to the datus and chieftains and planting orchards do not replace the equal ecological function of the forest and natural ecosystems that that footprint might affect,” he said.

In April 2021, the PCSD announced plans to review the criteria by which core and restricted zones are designated. Scientists like Mallari agreed that a revision was necessary if only to protect species that live in lowlands, since core zones were primarily confined to high-altitude areas. Activists however saw it as a move to accommodate more mining projects.

If it were up to Corio, mining activities in Bataraza should stop. He says he doesn’t know where the government’s loyalty lies.

“Ano ba itong gobyerno? Saan ba sila? (What is this government? Where do they stand?” he asks. “Ako, nagsasalita ng tapat. Kung saan ba sila — sa maliit na tao or malalaki nagpapabor (I’m speaking sincerely. Where do they stand — with the small people or do they favor the big ones)?”

Andrew W. Lehren is a senior editor with the NBC News Investigative Unit and a fellow with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

Anna Schecter is a senior producer with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Rich Schapiro is a reporter with the NBC News Investigative Unit.

Rachel Ganancial of Palawan News and Sofia Bernice Navarro, Ma. Cecilia Pagdanganan, Kyla Ramos and Martha Teodoro of PCIJ contributed research to this story.

Photographs: Kimberly dela Cruz

Infographics: Karol Ilagan and Joseph Luigi Almuena

Follow PCIJ on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. — PCIJ, December 2021